On the 130th anniversary of George Blake’s birth, Fraser MacHaffie pays tribute to the author who celebrated our native waters in the postwar classic The Firth of Clyde.

It was 1959 when I came out as a steamer ‘nutter’. From 1952 to 1959 I spent my summers working with a boat hirer on the beach at Largs. My employer wasn’t too good with numbers and so at the tender age of 11 I was made responsible for collecting the money for the hire of rowing boats and self-drive motorboats – good training for a future chartered accountant and ship’s purser — before graduating to the launches. In 1959 I decided I was ready for the bigger stuff and made my first trips on the Clyde fleet. Especially relevant was a visit to Paisley Harbour in 1959 by Countess of Breadalbane on a CRSC charter. By then I had already joined this group of people who had the same interests.

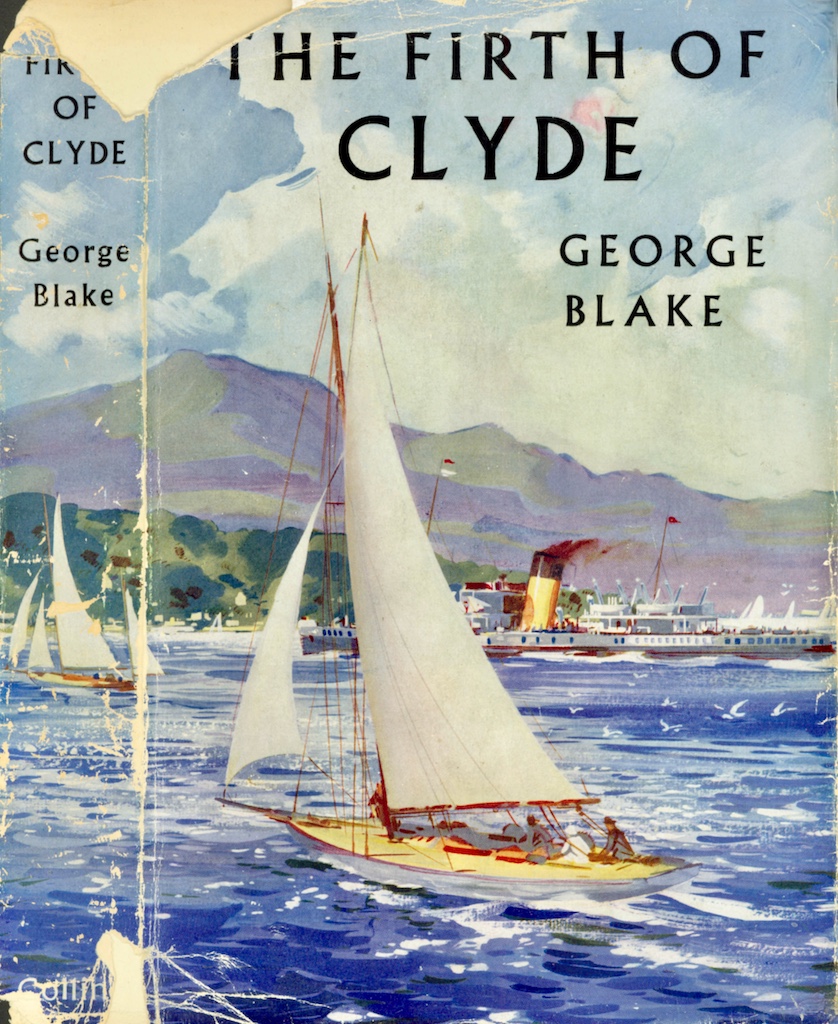

My ‘library’ consisted of three books: Captain James Williamson’s The Clyde Passenger Steamer, which was effectively on permanent loan to me from the Motherwell Public Library; CRSC member Peter Milne’s Clyde Steamers and Loch Lomond Fleets in and after 1936; and George Blake’s 1952 The Firth of Clyde. My copy of The Firth of Clyde was purchased in March 1959 and opened up for me the extent of the unexplored Firth.

George Blake in his prime. As well as publishing more than 20 novels, he became a noted broadcaster and commentator before and after the Second World War, and was editor of the Glasgow Evening Citizen in the early 1940s. He married into the Lawson family of lemonade factory fame, and had two sons and a daughter

This past weekend saw the 130th anniversary of George Blake’s birth, and a brief appreciation seems appropriate. I will also describe two of his popular novels featuring the Firth, shipbuilding and the estuarine steamers.

George Blake was very aware of the Clyde River Steamer Club. In the final chapter of The Firth of Clyde, he describes the Club in the following terms: “The existence in Glasgow of the Clyde River Steamer Club, numerous and enthusiastic, witnesses to the existence of a regional cult, one had almost said of a regional poetry. The literature of the cult, ever since Captain Williamson produced his classic, had so grown by mid-Century that an enthusiast could line a shelf of his bookcase with works of specialist devotion…. The nostalgia of the middle-aged apart, this mass sentimentality confesses a regret for glories departed and beyond recall; and it is the fact that, during [the] third, fourth and fifth decades of the 20th Century, much of the old gaiety and colour of scene disappeared from the Firth of Clyde.”

Blake was born on 28 October 1893 at 60 Forsyth Street, Greenock. The substantial building still stands at the corner of Forsyth and Brisbane Streets. For much of the 19th century, Greenock was reckoned Scotland’s sugar capital and George’s father, Matthew, a manufacturer of sugar machinery, shared in the wealth generated. The young Blake was educated at Greenock Academy. His law studies at Glasgow University were interrupted by the First World War when he joined the 5th Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders. He was wounded at Gallipoli in April 1915.

In his semi-autobiographical Down To The Sea, Blake describes with some bitterness his experience and that of the 50 men under his command at Gallipoli. It is not clear whether Blake’s wartime experiences influenced his choice of profession, but after the war law studies at Gilmorehill were abandoned in favour of journalism. Blake joined the staff of the Glasgow Evening News while Neil Munro of Para Handy fame was editor.

Blake’s first novel, Mince Callop Close, was published in 1923. The setting was Glasgow’s slums, though reckoned to be based on his knowledge of poverty in Greenock from which town the title was derived. The cast of players is headed by a female gang leader. The story is told with the realism expected of a left-leaning journalist. Mince Callop Close was an actual cul-de-sac in a desperate part of Greenock, while Mince Callop is a dish combining ground beef and oats.

From Down to the Sea, published in 1937, we learn that from an early age Blake was fascinated by ships. He relates the family legend describing the toddler Blake being wheeled along Greenock Esplanade in a perambulator and pointing to the Anchor Line’s City of Rome and gurgling, “Our ship!” The youngster Blake would spend his Saturday mornings, summer and winter, wandering the harbours of Greenock. In the summer his day would often start at Princes Pier watching the former G&SWR paddler Jupiter leave for Arran. In winter he would check on the laid-up steamers.

Front cover of Blake’s 1935 novel The Shipbuilders. It fictionalises the hardships and social divisions of the early 1930s on Clydeside. The book is still available on the internet

One of Blake’s most vivid early memories was the abandonment of a piano lesson so that the 13-year old and his teacher could go down to Greenock’s Customhouse Quay to watch Cunard’s Lusitania coming down from John Brown’s Clydebank yard for sea trials. Some three decades later, Blake pondered “Was it the size of her, that great cliff of upperworks bearing down at him? I think that what brought a lump to the boy’s throat was just her beauty… that men could fashion such a thing by their hands out of metal and wood was a happy realization… He knew he had witnessed a triumph of achievement such as no God of battles or panoplied monarch had ever brought about.”

The Shipbuilders, published in 1935, is considered Blake’s most successful novel in terms of sales and as a piece of literature. It was adapted as a film in 1943 without change in name. But the novel had to contend with competition in the form of No Mean City, a novel published in the same year and with the same concerns shaping The Shipbuilders — namely poverty and social divisions. No Mean City was co-authored by Alexander McArthur, an unemployed baker surviving in poverty in the Gorbals, and H. Kingsley Long, a London-based journalist. It sold more than half a million copies. Not much benefit came to McArthur, an alcoholic, who committed suicide by throwing himself into the Clyde.

The background for The Shipbuilders is the depression of the 1920s and 1930s, as typified by the rusting hull number 534 of the future Queen Mary at the John Brown yard at Clydebank. Construction work had been suspended in December 1931, throwing thousands into long term unemployment. One of its protagonists, Leslie Pagan, gives a frighteningly negative prognosis as he reflects on the collapse of the entire shipbuilding industry. His conclusion was that “The fall of Rome was a trifle in comparison.”

The key event in The Shipbuilders is the closure of a shipyard as experienced from two perspectives — Pagan, son of the retired owner of the shipyard as it slips into bankruptcy, and a riveter, Danny Shields. The class differences between them are explored, as is the bond they share with the yard.

While the story line of The Shipbuilders is fairly predictable and the characters verge on the stereotypical, Blake employs his ample skills as a wordsmith throughout. We find ourselves walking down Dumbarton Road with Danny Shields or arriving at the Kelvinside house of Leslie Pagan.

In keeping with his status in society Pagan operates in a paternal style and talks about the employees as “his men” and “Pagan’s Boys”. He has conflicting loyalties, however. He proclaims that “Glasgow is his city” but realises that it is a city that “has had its day”. His wife Blanche is a scion of a monied English family. She hates the grime and grey of Glasgow, and for her the collapse of the Pagan shipyard is good news. She has hired a ‘European’ au pair to look after son, John, justifying this decision by proclaiming, “If [John] has to be brought up in Glasgow, at least he can be taught to speak decently.” Tension is never far away in the marriage and “Always she seemed able to defeat [Pagan].” In the “blackness of introspection”, facing a future in English society where he has always felt a stranger, with its partying and shopping in London’s fashion palaces, Pagan declares, “Life is building ships, and not this luxuriating among redundancies.” Leslie Pagan comes over as a rather pathetic figure with a lasting sense of guilt over the closure of the shipyard.

Blake in later life. Described as “a thickset, battering-ram of a man, with a frowning brow and unruly hair”, he was renowned for his powers of graphic description. He died in in Glasgow in 1961

The closing of the yard sent Danny Shields, wife Agnes and three children into “hopeless insecurity.” A compounding factor was, that, whether he recognised it or not, riveters were becoming obsolete as welders were moving into shipbuilding. Through the Shields family we are given a glimpse into the day-to-day struggle of life even for someone with a skill like Danny’s.

Violence is never far away. We go with Danny to a Rangers-Celtic football match at Ibrox where the spectators are physically divided by religious affiliation. Most football violence erupted in the pubs after the match. The eldest son Peter has drifted into a gang and winds up in the dock at the High Court after an inter-gang altercation had left one of the opposing gang dead. Danny and his 10-year son Billy are attacked while selling bundles of firewood. Through all this, Danny is proud of his home in a tenement block on Glasgow’s South Side — one room, with recess bed and kitchen plus bathroom. The door has his name on a brass plate. Danny concedes that Agnes runs an efficient house — until he loses his status as the family’s wage-earner.

Life at home becomes an undeclared war as Agnes wants more of the good life and spends more time with her sister Lizzie and husband Jim, “who earned big money in mysterious ways.” Danny eventually erupts, attacks his sister-in-law’s husband and is frog-marched off to Barlinnie for a few days. Agnes deserts the house, but Danny finds a more congenial berth.

I’ll leave you to find the wrapping up of the Pagans and the Shields. A few days ago, I re-read The Shipbuilders. It’s still a good read.

The Westering Sun: A Novel was published in 1946 and traces two generations of the Oliphant family from around 1880 up to the Second World War. Blake’s politics are again visible, and a second family, the Bells, provide a foil for Blake as he “denounces capitalism, with all its fantastic extremes of enormous wealth and desperate, hopeless poverty.” Unlike The Shipbuilders, we do not encounter the ‘extremes’ but rather are provided with a contrast between the monied middle class and an emerging stratum of society seeking entry into a professional middle class. The Oliphants come to represent the wealthy middle class whereas Callum Bell, a master mariner, and his wife Betty, with their entrepreneurial flair, represent a new aspiring segment of society.

As teenagers, Callum Bell and Julius Oliphant, eventual patriarch of the family, were best friends. Early on in the tale, however, Julius “clypes” on Callum when they become innocently caught up in an attempt to smuggle cigars and spirits into the country on a beet sugar ship from Hamburg. We begin to see the boys gradually growing apart. This distancing continues when Julius, on achieving his majority, receives a bequest from an American relative which takes his family from being “comfortable” to “wealthy”. The consensus is that none of the Oliphant family, except the daughter Bluebell, did an honest day’s work in their lifetimes.

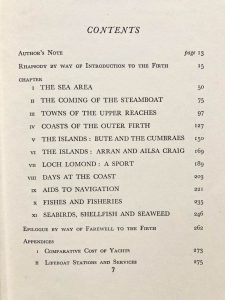

Contents page of The Firth of Clyde. Blake’s 34-page preface, titled ‘Rhapsody by Way of Introduction to the Firth’, is a glorious evocation of a pre-war journey by steamer to the Kyles, his prose alighting on many of the long-lost quirks and characteristics of life on board — seen through the eyes of two 12-year old boys

Despite the use of fictional names for places, CRSC members will easily recognize the geographic setting of the novel as the upper Firth of Clyde, with Garvel and Ardhallow featuring significantly. Likewise the steamers crossing the pages: most have fabricated names such as Caliph, Ruby and Saturn owned by the London and Western Railway. Edinburgh Castle is allowed to use her given name.

With a degree of “truthiness”, both the Oliphant and Bell families are involved in two significant events in Clyde steamer lore. Around the mid 1880s Julius Oliphant funds a remarkable paddle steamer, “The People’s Yacht”, built to give the more genteel a day of sailing free of alcohol-fuelled brawls. Named Heather Bell, the ship’s technical side of design and operating was the responsibility of Captain Calum Bell. It was declared that nothing like the elegance of the ship had been seen in that part of the globe before. What deeply impressed/depressed the reporter from the local newspaper was the total absence of alcoholic refreshment. (This, of course, was Ivanhoe of 1880.)

Blake’s account of the excitement surrounding Heather Bell is very credible. For example, the society painter, Greenock-born Sir James Guthrie (1859-1930), executed a pastel of a deck scene on Ivanhoe. Guthrie was a member of the Scottish painters dubbed the Glasgow Boys. Middle class life subjects were popular with the group and the pastel is now part of the National Galleries of Scotland collection.

The other event was a board meeting of one of the railway companies where two new turbine steamers, Princess Alexandra and Princess Louise, were on the agenda as possible threats to the company’s ships. The chairman of the board was very impressed with the quality of service on the turbines, but had concluded that the new ships would develop their own trade and did not represent a threat to the railway ferries. (Was he correct?)

Global as well as regional affairs impinged on these two families: the Boer War, the Great War, Spanish Flu outbreak, industrial turmoil of the 1920s, the Spanish Civil War and the Second World War, with our narrative finishing with the March 1941 Clydeside blitz.

I’ve heard the CRSC referred to as the intellectual wing of the steamer enthusiast population. So, now that the nights are drawing in, grab a Blake book from your local library and visit the river and its industries of a century ago.

The 1946-47 photograph of Jeanie Deans that adorned The Firth of Clyde with the caption ‘Lawful Occasions’

Published on 30 October 2023