Interview with John Whittle, General Manager of Caledonian MacBrayne Ltd from 1973 to 1983

In the third of a series of articles marking CalMac’s 40th anniversary, crsc.org.uk talks to John Whittle about the company’s early years.

When John Whittle became manager of the Caledonian Steam Packet Company in 1969 under the aegis of the newly formed Scottish Transport Group, the Clyde and Loch Lomond fleet consisted of 12 passenger vessels (five of them steam-driven) and four car ferries. Four years later the CSP merged with David MacBrayne Ltd to form Caledonian MacBrayne Ltd, with Mr Whittle as general manager, and by 1983, when he handed over to Colin Paterson, the combined Clyde and Hebridean fleet consisted of 22 car ferries of varying sizes, one passenger/cargo vessel (Lochmor) and just one passenger vessel (Keppel). That is a measure of the transformation he effected during his 14 years in charge.

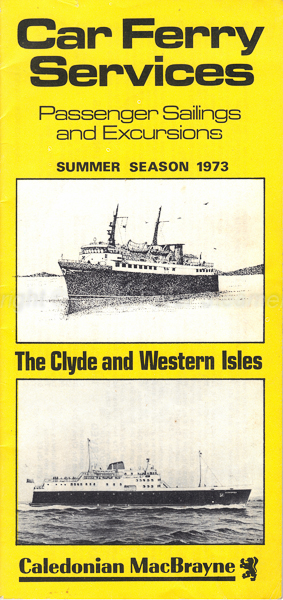

CalMac’s first summer timetable

Now 80, Mr Whittle lives near Carstairs in Lanarkshire and seems as interested in west coast shipping as ever. After giving up his executive responsibilities at Gourock he became the Scottish Transport Group’s head of planning, marketing and public affairs, based at its Edinburgh headquarters, though he remained a CalMac director. He retired when the STG was wound up in 1989. His links with the CRSC go back to 1972, when he was guest of honour at the Club’s 40th anniversary dinner. He was again guest of honour at our 80th anniversary celebration in November 2012.

Born in London in 1933, John Whittle was evacuated to Chichester during the early years of the second world war and moved to Scotland in 1942, after his father was sent north to manage a military supply depot at Rouken Glen, Glasgow: the family arrived a few days before Clydebank was blitzed. Following four years of study for his Chartered Institute of Transport exams, Mr Whittle worked first for Glasgow Corporation Transport and then the Motherwell-based Central SMT bus company, where he became traffic manager. When, in 1968, Mr Whittle was summoned for a meeting at Scottish Bus Group headquarters in Edinburgh in advance of the STG’s formation, he had no idea he was being groomed to assume responsibility for the new transport conglomerate’s shipping arm.

“It was a major culture shock,” he recalls, when asked about his move to Gourock in 1969. “I remember asking myself ‘What the hell am I doing, taking this on?’.” At Central SMT he had become accustomed to working at “a very profitable company”. For its part, the CSP had “a great many reservations” about a bus manager taking over, while in the islands there was “a lot of concern about what we were doing”. Trying to get the company to turn in a profit on bus company lines “would have necessitated a sacrifice in quality and price. The other way to go was to improve productivity and quality of service. We weren’t just a business. We had a responsibility to the community.”

And so raising productivity became a primary goal, starting at the CSP’s Gourock headquarters. “There was an ‘officers and ranks’ mentality, with all levers of power vested in one pair of hands,” he says. “Every letter had to be signed by the general manager. Every notice ended with ‘by order of the general manager’. No one, apart from the general manager, had any financial information. The business was run on a ‘bums on seats’ principle, rather than profit/loss. No one asked what financial impact their actions had on what they were doing. That was alien to me. I wanted management to work as a team, with common objectives and common responsibility. I found some excellent people working for the company, and they responded extremely well. They were very loyal and I relied on them a great deal. It was the same with MacBraynes when the two companies came together in 1973. Of course, some were too lazy or set in their ways to change, but they were very much a minority.”

When the CSP and MacBraynes were merged, the STG decreed there were to be no redundancies. Given that both companies had their own traffic manager, company secretary and so on, a series of ‘assistant’ posts had to be created until someone took retirement. “It meant we were top-heavy for a while,” says Mr Whittle. However, MacBrayne buses had already been hived off, and a decision was taken to manage the cargo ships under a separate subsidiary, using the old David MacBrayne company title, “so that their performance didn’t [financially] drag down CalMac in the years before the ships were withdrawn.”

And so none of the surviving cargo ships adopted CalMac’s red lion on the funnel. The Loch Carron was the last to make the historic ‘all the way’ sailing from the Clyde to the Hebrides in October 1976.

|

|

|

| Loch Carron at Lochboisdale | Built with only one rudder, Columba and her two sisters had constant manoeuvrability problems |

Upgrading the MacBrayne network was a greater challenge than the CSP, “because the western isles had been late in getting car ferries. Part of MacBrayne’s problem was that it had been subject to government interference, so you got cases like the Hebrides, Clansman and Columba, each built with a single rudder as a cost-saving measure — whereas the CSP, a railway subsidiary, wasn’t directly controlled by the government, and had had generous capital investment in the 1950s.”

Nevertheless, there were problems common to both arms of the business. One was the way CalMac was perceived by the public at large. “There was a love-hate relationship with users and the public, and we had a pretty poor press. When you make a mistake in a factory environment, it doesn’t usually pass the company gate. In transport, it’s immediately in the public domain. One of the things I was concerned to do was improve the relationship with our users, so we could have a better understanding of them, and them of us. We set up three shipping services advisory committees — Clyde, western isles north and western isles south — and invited all local authorities, crofters’ associations and farmers’ bodies to nominate members, and that’s how we improved our relationship with island communities. It stopped us making mistakes that would have been costly to us and costly to them. That sort of consultation was revolutionary — though we still got our fingers singed.”

Another problem common to the Clyde and Hebridean services inherited by CalMac was that not a single ferry route ran between two piers controlled by the same authority. “It was a problem we continually faced. Local authorities [who owned many of the piers used by CalMac ships] were strapped for cash and we either had to buy the piers or do the design and supervision work on their behalf. The Ardrossan linkspan was put in because the harbour authority was going to earn money on it, but it was only by buying Brodick pier and upgrading it that we got our first drive-through service: there would have been no hope of Arran Piers doing it.”

The harbour trusts at Stornoway and Ullapool saw the advantages and went ahead on their own, but “the big disappointment I had was the Uig triangle, the natural short route to the outer isles, where we were totally frustrated,” leaving the side-loading Hebrides to soldier on until 1985.

Hebrides soldiered on at the Uig triangle until 1985

Mr Whittle says the problem was compounded by the fact that the terminals at Uig, Tarbert (Harris) and Lochmaddy were controlled by different authorities, all with limited resources and vulnerable to local opinion. “There was widespread fear of us running on the Sabbath and considerable pressure to relocate to different terminals, such as Dunvegan in Skye and somewhere in the middle of the Uists. We finally cracked that by getting two professors from Aberdeen University to study the effect such a move would have on the islands. They concluded that the social costs of relocation would be greater than the savings, and recommended that the Uig triangle be upgraded to drive-through. We circulated the report to local authorities, and they saw the writing on the wall. The whole process cost us a lot in manpower and money, but in the end it was worthwhile.”

While CalMac’s fleet numbers went down during his time in charge, passenger numbers went up by a sizable percentage, as did car and freight loads, “and that had a significant effect on island economies. The thing I take a lot of satisfaction from was that we reduced unit operating costs by more than 30 percent. Overall costs went up but not as fast as inflation. That was the outcome of the productivity gains we made — we needed to sweat the assets to keep costs within bounds, because neither subsidy nor fares kept pace with inflation. The real beneficiaries of our 30 per cent productivity gains were the taxpayer and the ferry users.”

Those productivity gains went hand-in-hand with fleet renewal. Despite inflationary pressures and the drawn-out introduction of drive-through facilities, the 1970s saw the introduction of the Pioneer, the Claymore, the Suilven, the three ‘streakers’, the Isle of Cumbrae and the ‘Island’ class. How did CalMac finance it all? “We were fortunate in that there was a loophole in one of the regulations governing access to capital. The government had set up a ship mortgage fund — a system of cheap loans for British ship-owners who commissioned British-built ships. It was intended for the private sector, but because of the way it had been drafted we benefitted from it. That’s how we financed the building of the Juno, Jupiter, Saturn and the ‘Island’ class ferries.”

Despite his background in road transport, there has long been a suspicion in enthusiast circles that Mr Whittle himself was a closet enthusiast, an impression he makes no attempt to contradict — though his opinion of some boats was coloured by managerial experience of them. He was always proud of the streakers’ manoeuvrability. Of the car ferry conversions (Clansman, Arran and Maid of Cumbrae), the Cumbrae comes out top — “the prettiest car ferry in the fleet”. The Glen Sannox was “a rather elegant design as well as being a very versatile and useful unit”. He was especially pleased with the Lochmor because, during her design phase, “the Highlands and Islands Development Board showed an obsession with small vessels and prevailed upon the Scottish Office to approve a design of 84 feet in length. We were far from happy with this and the Secretary of State agreed to an increase to 100 feet, raising summer passenger capacity from 80 to 120.”

What about the role played in CalMac’s early years by Moris Little, STG managing director, and Pat Thomas, STG chairman? Mr Whittle, whose mild manner and astute judgement have won him friends in all walks of life, says Mr Little “was a guiding light for the whole group. He was at the heart of everything. Colonel Thomas set the climate for managers to act, and that’s the way it should be. Both were extremely good at keeping politicians away. Moris Little’s advice to me was ‘Do what needs to be done, John, and don’t tell the buggers until it’s too late to interfere’.”

It was Moris Little who persuaded the STG board to ‘sell’ the Waverley to the Paddle Steamer Preservation Society. The STG had inherited “six lovely steamers that couldn’t be merged with the ferry network. Their daily costs were too high, they sat in harbour all winter eating their heads off. We had to take a hard decision. But we didn’t want to scrap the last sea-going paddle steamer and were not enamoured of her becoming another bar on the Thames. Douglas McGowan and Terry Sylvester had contributed a number of marketing ideas [between 1971 and 1973]. They were trying to be helpful: their attitude was constructive. That’s why, 40 years ago this autumn, I asked Douglas to come and see me — and dumbfounded him [with the offer to sell the Waverley for a pound].”

Mr Whittle says there were strong arguments in the 1980s for privatising the entire CalMac network — arguments he had some sympathy with. “Privatisation would have enabled the company to branch out into other ventures, so that it wouldn’t be entirely dependent on winning government tenders. If it doesn’t win the next contract [for Clyde and Hebridean ferry services, in a bidding process due to be completed in 2016], what is it there for? Given the wave of privatisations in the Thatcher years, it was a strange decision not to privatise CalMac when the STG was dissolved in 1989 and the undertaking transferred to the Secretary of State. As a private company CalMac could have been more direct in its political demands, and put up two fingers to the politicians. A public sector company is a bit more constrained.”

He is sceptical of the tendering process that CalMac and its potential rivals will have to undergo in the run-up to 2016. “Because of the nature of tendering, the ships are specified, the routes are specified, the timetables are specified, and wages and conditions are tied by TUPE [Transfer of Undertakings (Protection of Employment) Regulations]. If CalMac lose the contract, any new company will have to take over staff and all existing conditions. There are not a lot of options for bidders to offer economies. The NorthLink contract was lost on the basis of the improvement in the quality of service that [the winning bidder] Serco could offer. But on CalMac routes? More frequent services at a lesser price? I don’t know how they’d do that.”

One final reminiscence: what really happened in Gunna Sound in the early morning 22 March 1973 when the Loch Seaforth ran aground, with the CalMac general manager and STG chief executive aboard? Mr Whittle says it was pure coincidence that he and Moris Little took the Loch Seaforth from Lochboisdale on that occasion. “We had gone to South Uist for a meeting with the local authority to see if they would sell us the pier. We thought they would need a month to consider our offer. To our surprise, within half an hour we had total agreement. So we went to the local hotel for a meal and Moris suggested we cancel the flight arranged for the next day and take the Seaforth back to Oban that night.

“[At 5.30 the next morning] I woke with a bang and a crash. Before I had time to shut my eyes again the steward came in and told me to get up on deck. The few passengers were put in a lifeboat, and the rest of us stayed on board until the Seaforth started to list. Donald Gunn, the skipper, decided to abandon ship. We got into the other lifeboat, and I remember one of the seamen saying ‘I’ve never been in Tiree since I was a toddler, I’m quite looking forward to seeing it again’. Donald Gunn was manning the tiller. He said ‘we’ll make for that sandy beach’, and all I could see was darkness and more darkness.”

Before the storm – LochSeaforth in East India Harbour, Greenock, next to King George V

Later in the day Captain Gunn took a skeleton crew back on board so that the Loch Seaforth could be towed to Scarinish, making the salvage job much cheaper. Meanwhile, the national press descended on Tiree by plane and helicopter, “but only one of the reporters twigged that the general manager and chief executive were on board, and got the scoop. I knew the captain and crew would handle the rescue well, and they did. The grounding and subsequent sinking of the Loch Seaforth marred CalMac’s first year. But it made me better disposed to the cost of safety drills.”

John Whittle was speaking to CRSC magazine editor Andrew Clark in August 2013.

Photographs courtesy of Andrew Clark, John Whittle, Douglas McGowan, the late A.E. Bennett and the estate of Walter and Effie Kerr.

This is the third interview in a series marking CalMac’s 40th anniversary. The first, featuring CalMac Managing Director Martin Dorchester, can be read here, and the second, with CMAL chief executive Guy Platten, can be read here.

Sign up for CRSC membership and further your interest in Scottish shipping.

witnesses the handover of the pound note.jpg)

.jpg)