John Gunn began his career as a catering boy on the 1964 Hebrides. He retired 50 years later,

on April 2 this year, as onboard service manager of Isle of Lewis

It must be some kind of record: John Gunn has worked on 22 MacBrayne/CalMac ships.

His first was the ‘old’ Hebrides in 1964, when he was a 15-year old. He also served on her two sisters, Clansman and Columba, the latter acting as his ‘mother ship’ for much of his early career. In the late 1960s he had spells on Lochfyne, Lochnevis, Lochiel, Loch Broom, Lochdunvegan, Loch Arkaig, Loch Eynort and the 1955 Claymore — not forgetting a day on Queen Mary II, when John, kicking his heels in Greenock while Columba was being overhauled, lent a hand in the ageing turbine’s galley on a busy charter to Inveraray.

He spent four summers on King George V and in 1974 was part of the delivery crew for Suilven. In the 1980s and 1990s he did stints on Isle of Arran, Hebridean Isles, Caledonian Isles, Pioneer and Iona — before and after her re-naming as Pentalina B.

Still counting? John was chief steward on Isle of Lewis from her debut in 1995 and, apart from brief spells on Isle of Mull and the 2000 Hebrides, remained on the Stornoway ferry for the following 19 years, latterly as onboard service manager. Yes, that’s 22 ships.

Talking of records, John can claim another: the Gunns have more MacBrayne connections than any other Hebridean family. His father Kenneth was an able seaman on the pre-war Lochdunvegan and several other MacBrayne boats, and his uncle Donald was the last skipper of the 1947 Loch Seaforth. Of John’s four brothers, Donald was master of Hebrides until his retirement in 2006 and Kenneth had a spell with MacBraynes as second cook. His sister Margaret and niece Aileen were stewardesses, and brother-in-law John an able seaman. First cousin Kenny became captain of Loch Arkaig at 28 and another cousin, Ian, was on the catering staff of Isle of Lewis. “Most of my family have had a MacBrayne connection,” he says, adding that the MacMillans of South Uist have begun to run them close.

|

|

|

|

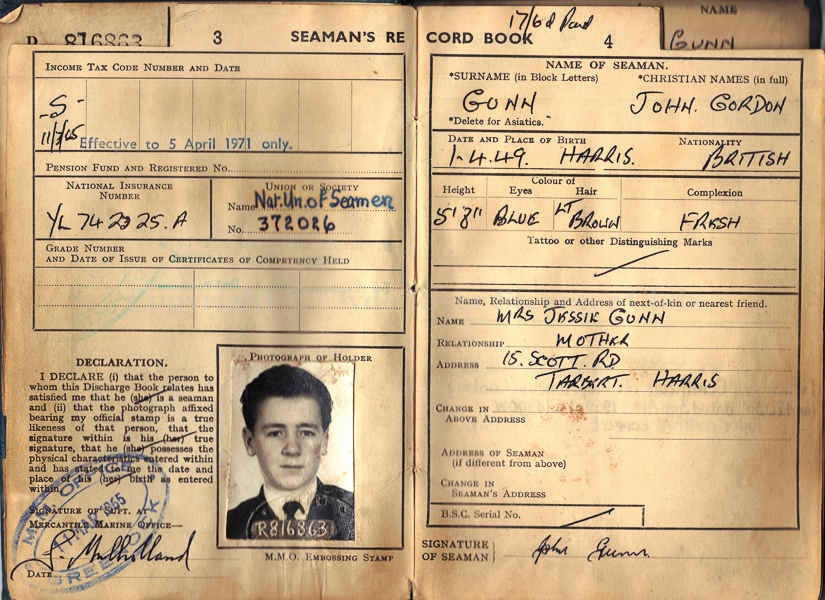

First discharge book — 11 March 1965

|

Queen Mary II at Inveraray

|

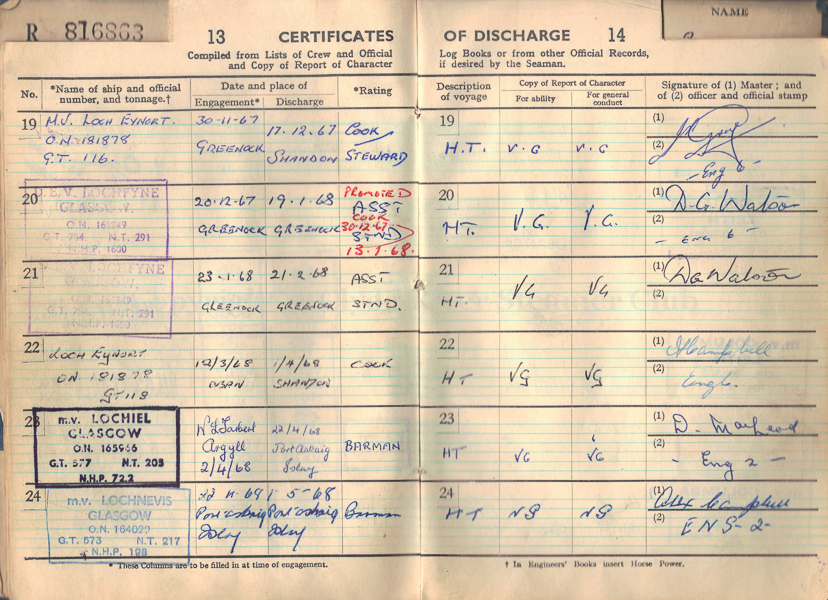

During the 1967-8 winter John worked on

Loch Eynort, Lochfyne, Lochiel and Lochnevis

|

|

|

|

|

Hebrides at Tarbert

|

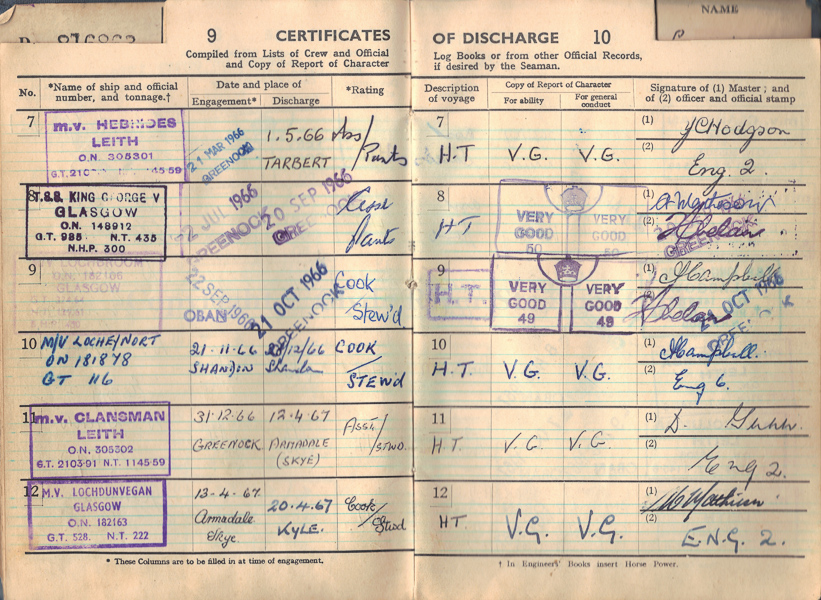

John’s discharge book mentions six ships between

March 1966 and April 1967 — Hebrides, King George V,

Lochbroom, Loch Eynort, Clansman and Lochdunvegan

|

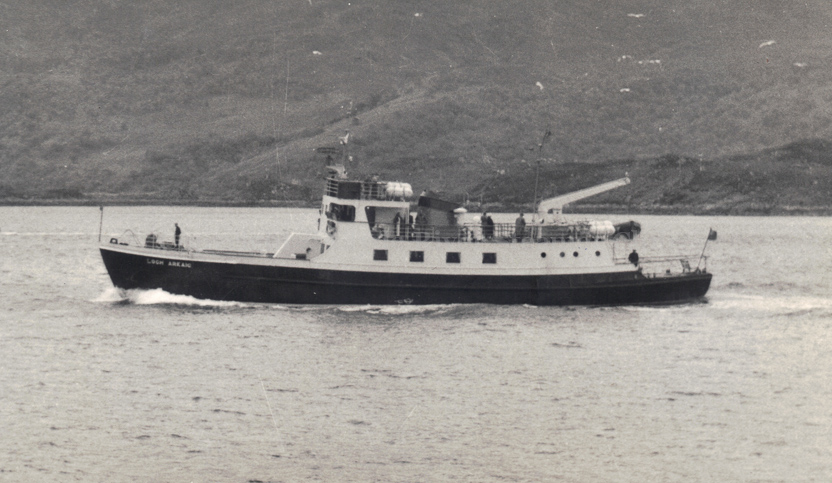

Loch Arkaig

|

It all began in Tarbert (Harris), where John was born on April 1 1949. Just over 15 years later, in June 1964, he finished school on the Friday and by the Monday was in the galley of Hebrides, one of the first-generation MacBrayne car ferries. “I’d never seen so many dishes,” he recalls. “A catering boy earned £4 10s 8d a week, but with overtime I could clear about £10 a week. You grew up quickly. It was a good run.”

In the winter of 1965, aged 16, he was sent to Loch Arkaig as cook: he had to buy the food and divide the cost by 10, the number of crew on board. “She was a nice wee ship.” It was a different system to the cargo ships, where the crew’s ‘victualling allowance’ — 28s per person per week — had to suffice for three meals a day.

“It could be done,” says John, “but if funds were getting low, I had to spend some of my own money rather than let them go hungry. The older cooks from Glasgow knew where to go to get good deals and build up a stock of food. They made it look a lot easier than a young guy like me. I remember my first morning on Lochdunvegan: I arrived to find a lovely warm stove, which got colder and colder. I couldn’t understand why. I asked the engineer if there was something wrong. ‘Have you tried putting in coal?’ he asked. I had assumed it was oil-fired like the rest.”

The contrast with King George V could hardly have been greater. “You were flat-out all the time, with just a wee break at Iona. We didn’t even have hot running water — just a steam pipe from the engine-room. We used to get train parties from down south — 200 or 300 for breakfast before we had even left Oban. The dining saloon could take 120. There were 12 tables with 10 places each, and a 13th table was kept spare. There were six waiters, each of whom looked after two tables. The crew accommodation was primitive: we used to wash ourselves with buckets of water, and you needed it after a day in that galley. You joined in May and that was you till September — you got days due at the end of the summer.”

|

|

|

|

King George V at Oban in 1971, with

Graham Langmuir in ‘plus fours’ beneath the aft funnel

|

Lochdunvegan (right) at Stornoway, with Iona

|

Columba at anchor in the Sound of Iona

|

He enjoyed working out of Oban. Columba, to which he transferred as second cook in July 1967, was “a good ship to be on. She had a good team — we were all young.” Columba took him not only on her regular run to Craignure and Lochaline run but also on the Iona excursion after King George V was withdrawn and the Uig triangle when she relieved Hebrides. It was on another winter relief — Loch Eynort — that John had one of his worst experiences. On her way back to Skye from overhaul in the Clyde she hit a storm off the Mull of Kintyre and the lifeboat was washed over board. “We took 24 hours from Campbeltown to Tobermory, a journey which would normally have taken eight to ten hours.”

John joined Suilven as chief cook for her delivery voyage from Norway in 1974. At that time she had no stabilisers, and although the voyage across the North Sea was smooth, there were more than a few uncomfortable crossings during her first winter on the Ullapool-Stornoway run. Suilven was “a good strong boat, bigger than her predecessors Clansman and Iona. She had a strong icebreaker hull, but from the interior point of view she was not the best. Passenger accommodation was pretty rudimentary. She had a certificate for 408, and if it was wet and people couldn’t get outside, she felt overcrowded. It was even worse after they stopped allowing people onto the car deck.”

When Isle of Lewis arrived in 1995, John took most of Suilven’s catering staff with him onto the new ferry: he had “a good team”. As chief steward (retitled ‘onboard service manager’ in 2006), John was responsible for 17 staff in summer, 11 in winter. Over the years various responsibilities were added to the job, such as making announcements on the public address system, interviewing job applicants and organising emergency musters — “though thankfully in my time we never had an emergency.”

From the catering point of view, the most distinctive feature of the Stornoway run was the number of ‘white knuckle crossings’, when the ship rolled so much that people didn’t want to eat. Food consumption was generally higher on the westbound crossing, because “most people had come aboard after a long road journey and needed something to eat. The 45 minutes of calm water in Loch Broom encouraged them.”

How do today’s working duties compare with the old days? John says documentation has got out of hand “and I don’t know where it’s going to end. It’s got to the point where you can’t even throw a slice of bread to the seagulls — with new rules on dumping rubbish at sea, introduced in January this year, you can’t use the garbage disposal unit until you’re three miles from the shore, and the bridge has to record the ship’s position when it’s done.”

Modern crew accommodation has also diluted the working atmosphere on board. “In the old days after a meal, we’d all sit together in the mess room and have a smoke and a blether, maybe a wee ceilidh. Now everyone goes immediately to their cabins and laptops, and we’re not allowed to smoke.”

Of the many captains John served under, he singles out John Norman Macdonald, also from Harris, for his “calmness, authority and ship-handling. He knew the run, he knew the ship. He had it all.”

Captain Macdonald retired a decade ago: his last ship was Isle of Lewis. Now John Gunn has followed suit. In so doing he has denied himself the chance to serve on the new Loch Seaforth — just as, by a quirk of fate, he never served on her 1947 predecessor.

The transition to retirement was eased by CalMac’s shift system of two weeks on, two weeks off, with six weeks’ annual leave. John and his wife Cathy, who met in Stornoway’s Caledonian Hotel and married in 1976, have lived at nearby Gress since 1978. There are no fancy plans for travelling, apart from occasional trips to Inverness and Aberdeen to see their two daughters and granddaughter. Asked whether, after 50 years of supervising the galleys of Hebridean ferries, he has now assumed responsibility for cooking at home, John laughs and says “Sunday lunch only”.

John Gunn was talking to CRSC magazine editor Andrew Clark in August 2014.

Sign up for CRSC membership here and further your interest in British coastal shipping.