|

|

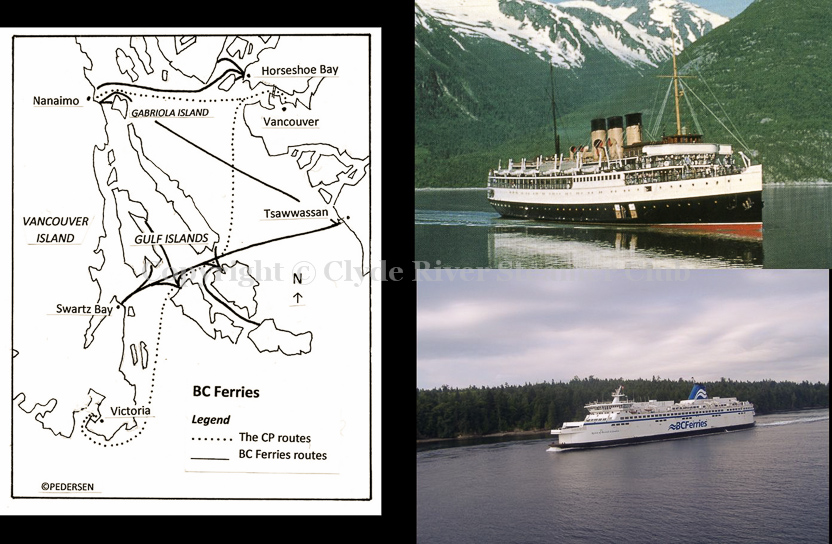

Shortest possible crossings, efficient vessel design, lower emissions: in Mr Pedersen’s scheme, all this translated into lower costs, lower fares, lower subsidies, more frequent travel opportunities, greater capacity (by dint of greater frequency), faster journey times and more sustainable communities. Islay could be a beneficiary of this template, if traffic were to be channelled through a short crossing between Jura and the mainland. But, deterred by the short-term cost of upgrading roads, government officials had dismissed the proposal. As for Mull, Mr Pedersen poured scorn on CalMac’s winter timetable, saying it was “extraordinary” that, for a passage-time of just 45 minutes, the last boat left the mainland as early as 4pm. However, he acknowledged that demand for evening services varied from community to community.