Ian McCrorie introducing his talk

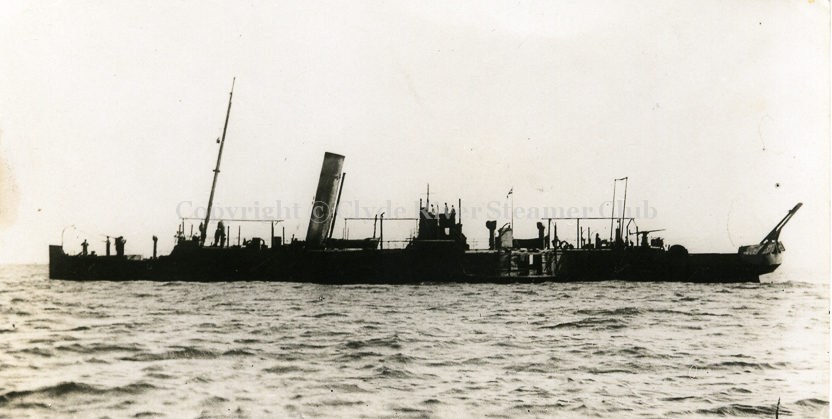

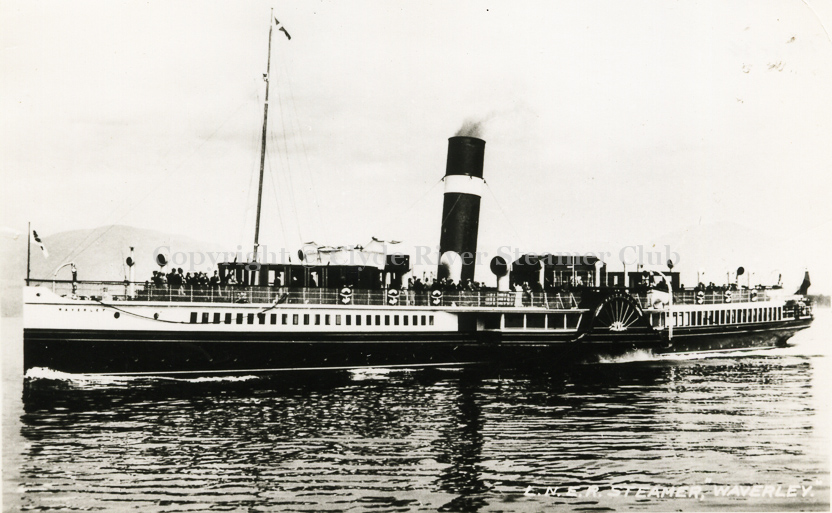

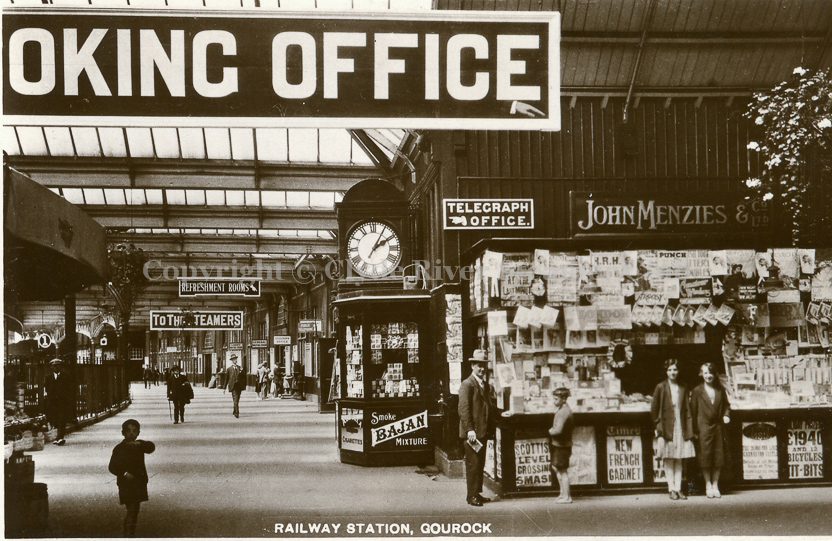

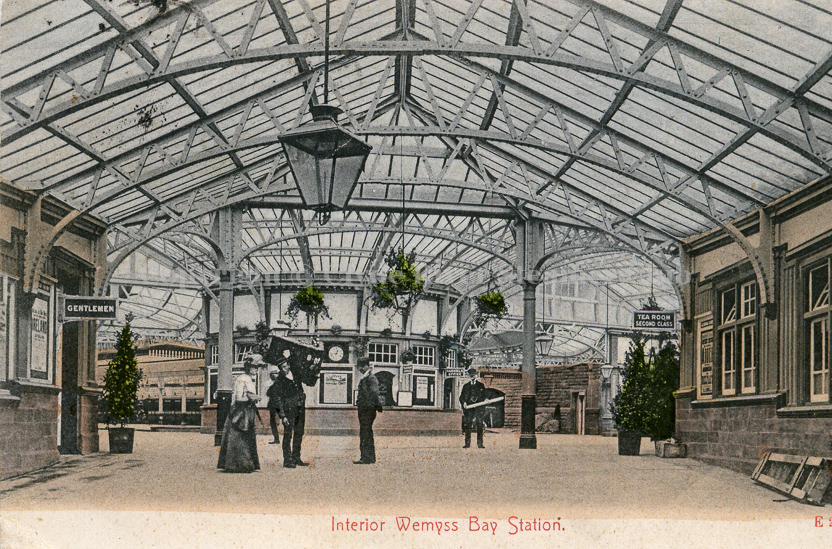

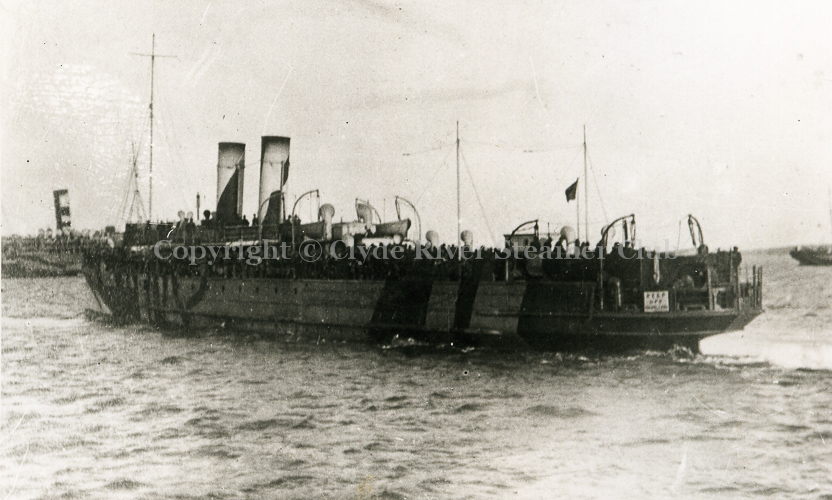

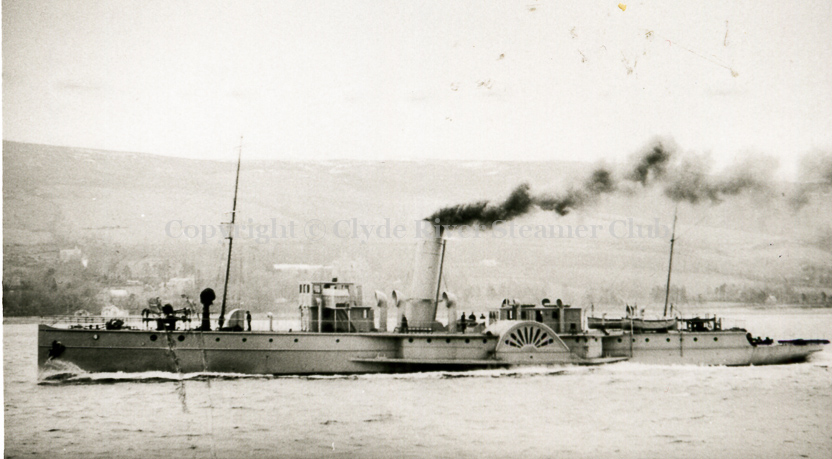

Images from Ian’s presentation are shown throughout this report as representative of his talk and to give readers a perspective of the Clyde, and the Clyde Steamer scene, in the period 1914 to 1918

Steamer dreamers love the minutiae of timetables and ship movements, but it’s good, occasionally, to be reminded of the political and international context in which they operate — an element kept beautifully in balance throughout ‘Clyde Steamers in World War 1’, the subject of the January 14 meeting at Jurys Inn. The speaker, poetically introduced by CRSC president Angus Ross as ‘the Bard of the Clyde steamers’, was Ian McCrorie, who justified his title (as on several previous occasions) by launching into song at appropriate moments in his talk. This time it was his rendering of ‘Lloyd George knew my father’ to the tune of ‘Onward Christian soldiers’ that best captured the imagination, for the great Liberal politician was at the height of his powers during the so-called ‘Great War’.

|

|

|

|

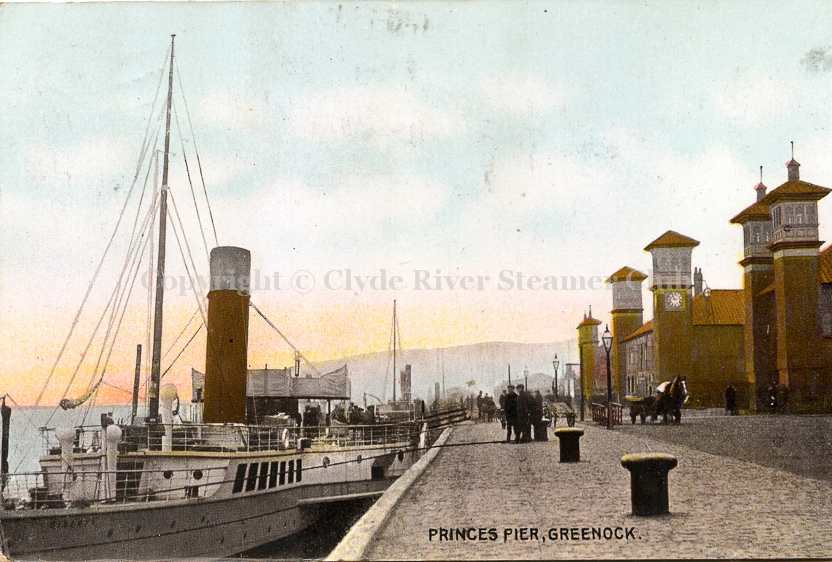

| Gourock railway station in its Caley heyday | Wemyss Bay station circa 1910 | A ‘Marchioness’ at Largs | Minerva at Princes Pier |

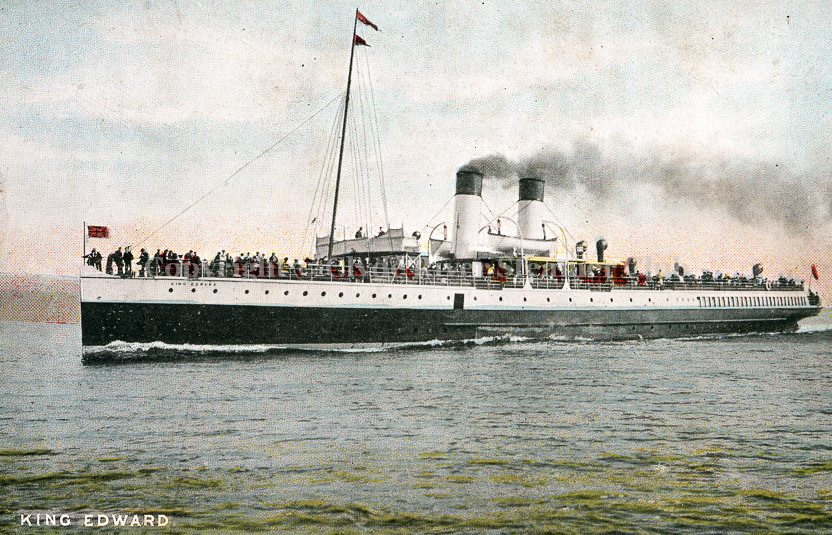

It was a war in which the Clyde’s steamers played a noble part, fulfilling their duties in the face of terrible odds, and proving their worth hundreds — sometimes thousands — of miles from home: Minerva ended up in Constantinople; Kind Edward and Queen-Empress sailed to the White Sea and back. Painting the background to the war, Ian cited 1906 as the ‘high noon’ of the railway steamers, his first illustration depicting a radiant Duchess of Argyll in a Caledonian Steam Packet Company poster. Then came the 1909 pooling arrangement, a brief resurgence of ‘all the way’ traffic from Glasgow and the eerie calm of the summer of 1914, as if the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria in Sarajevo on June 28 had taken place in another world. But the German bands quickly disappeared, the railway company’s pooling arrangement was cancelled and by Christmas British soldiers were in the trenches — their rendering of ‘Silent Night’ finding a response across enemy lines in the Germans’ ‘Stille Nacht’ (cue another harmonious launching-into-song from our speaker).

|

|

|

|

| Dunoon with two NB steamers | King Edward | Queen Alexandra at Lochranza | Kylemore at Dunoon |

Of the steamers engaged in troop transport across the English Channel, Duchess of Argyll had the most distinguished record — 655 trips in all, covering a distance of 71,000 nautical miles. Early casualties included the CSP’s Duchess of Hamilton and Duchess of Montrose, the latter looking remarkably pretty in naval black — one of the most memorable illustrations of the evening.

|

| Duchess of Montrose |

If 1915 was notable for the introduction of the Cloch-Dunoon boom, Glen Sannox’s brief appearance on the south coast and Columba’s year-long layup, 1916 saw the advent of conscription, the loss of Fair Maid (the NB’s new paddler, launched too late for peacetime service), the requisitioning of Grenadier (the only MacBrayne vessel to go to war) and the CSP’s chartering of Iona.

|

|

|

|

| Linnet at Ardrishaig | Waverley during World War I | A gathering of minesweepers | Duchess of Argyll on trooping duty |

So depleted was the CSP’s fleet by 1917 that the distinctive dark blue hulls vanished from the Clyde: Ivanhoe’s was painted black as an economy measure. Among the most memorable illustrations here were an ‘all hands on deck’ army parade outside Greenock Town Hall, the sight of Fusilier at Craigmore in Caley colours and the blown-off bow of Mercury. Isle of Arran was the last to head south with gun turrets, late in 1917. War continued for another year — until Armistice Day on the eleventh day of the eleventh month of 1918, by which time nearly a million soldiers from the British Empire alone had died.

|

|

|

|

| Mars at Cove | Marchioness of Lorne | Duchess of Hamilton | Fair Maid |

The welcome dismantling of the boom in February 1919 coincided with less welcome news — the death from pneumonia of Captain James Williamson, progenitor of the golden era of railway steamers on the Clyde. The remainder of the year saw the signing of the Treaty of Versailles (bringing a formal end to the war on June 19) and a steady stream of steamers returning home. Kenilworth was the first of the Clyde’s reconditioned paddlers to resume service, sailing from Craigendoran to Rothesay in early May. Duchess of Rothesay was less lucky: she sank at Merklands Wharf on June 1, and remained underwater for nearly eight weeks.

|

|

|

|

| Columba and Iona at Ardrishaig | Queen-Empress on war duty | Ivanhoe with black hull and paddle-box | Glen Rosa at Ilfracombe |

That summer Campbeltown Company steamers returned to Glasgow for the first time since 1914, Columba resumed her time-honoured Glasgow-Ardrishaig roster, now without Post Office, and Waverley took on a new look, emerging with promenade deck extended to the bow (making permanent the form in which she had spent the war years).

|

|

|

| Chevalier at Colintraive | Lord of the Isles | Marchioness of Lorne after the war |

It was nevertheless a slow return to ‘normality’. King Edward and Queen-Empress continued their Russian exploits long after war ended, Minerva never returned from the Bosphorus and Marchioness of Lorne lay neglected in Bowling Harbour until 1923, when she was broken up. Despite the resumption of peacetime colours, the ‘high noon’ of the Clyde’s steamers was well and truly past.

CRSC members recognise an authoritative talk when they hear one, and everyone listened to ‘the Bard’ with rapt attention. In his vote of thanks, Stornoway-based Colin Tucker compared the differing impact war had had on the Clyde (as outlined by Ian McCrorie) and the Hebrides. The message of war is never cheerful, he said, but the variety and range of material covered in Ian’s talk had enriched everyone.