Fraser MacHaffie

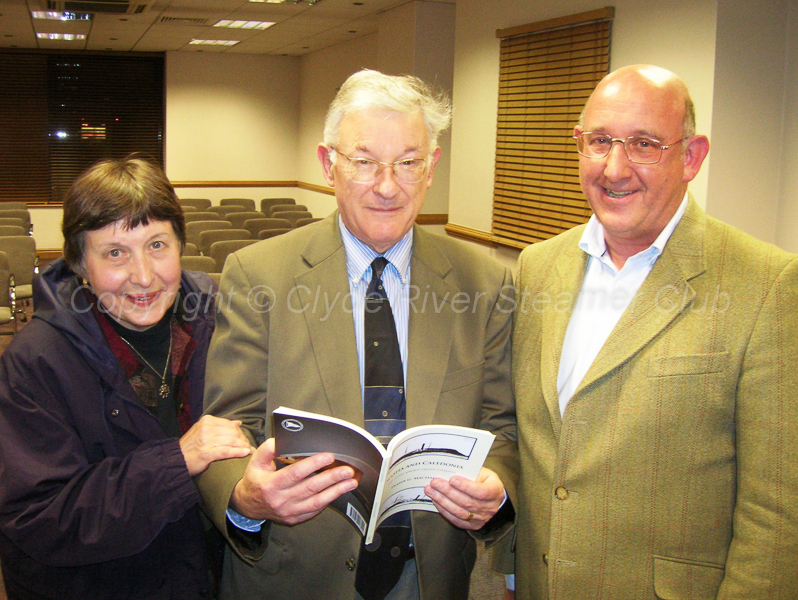

The first meeting of the CRSC’s 2013-14 winter session was held at Jurys Inn, Glasgow, on October 9. The speaker was steamer historian Fraser MacHaffie, who played a significant role in the Club’s 1960s rejuvenation before following a distinguished academic career, latterly at Marietta College, Ohio, where he now lives. This was the third time in as many years that Fraser had crossed the Atlantic to address the CRSC. His talk, titled “Aspects of Blockade-Running”, coincided with the Club’s publication of his latest book, “Scotia and Caledonia”, a tale of two little-known Clyde paddlers that crossed the Atlantic to run the blockade in the American Civil War.

The 104-page volume was on sale at the meeting, and after his talk, which kept a packed room of members and friends enthralled for just over an hour, Fraser did a book-signing. Those unable to attend the October meeting should have received information on how to purchase the book with their autumn mailing. Non-members will be able to buy it on crsc.org.uk from mid-November.

Fraser MacHaffie at the book-signing after his talk,

with Club member Colin MacNab

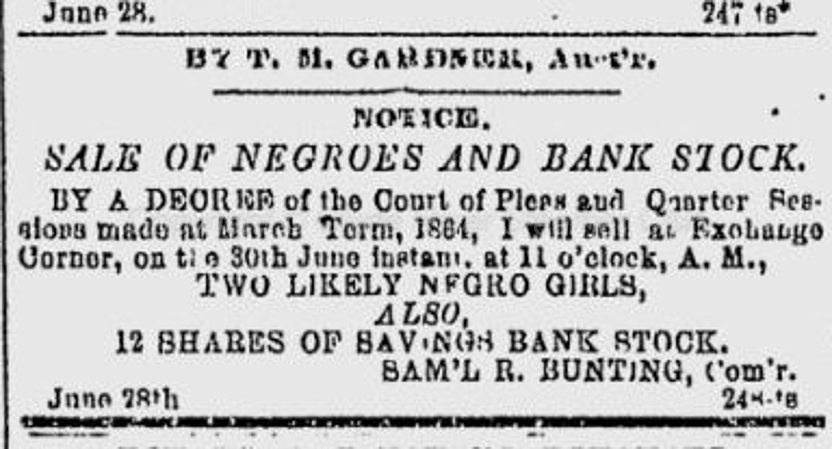

One of the most fascinating elements of Fraser’s talk was his exploration of the political and economic background to blockade-running, often glossed over in steamer histories. We learned of the vibrant trade links between the southern states and the UK, of the potential threat to British exports from the northern states’ industrialisation, of the importance of southern cotton sales to pay for the war and the hypocrisy of British neutrality. Fraser showed a photograph of an 1860s shop-front in Atlanta, Georgia, advertising “Auctions & Negro Sales”, and a 1864 advert for “Sale of negroes – two likely negro girls – and bank stock”. Both were symptomatic of the human trafficking that went on in the breakaway states — a trade aided and abetted by British exports to the Confederacy.

Trafficking in slaves was aided and abetted

by British exports to the Confederate states

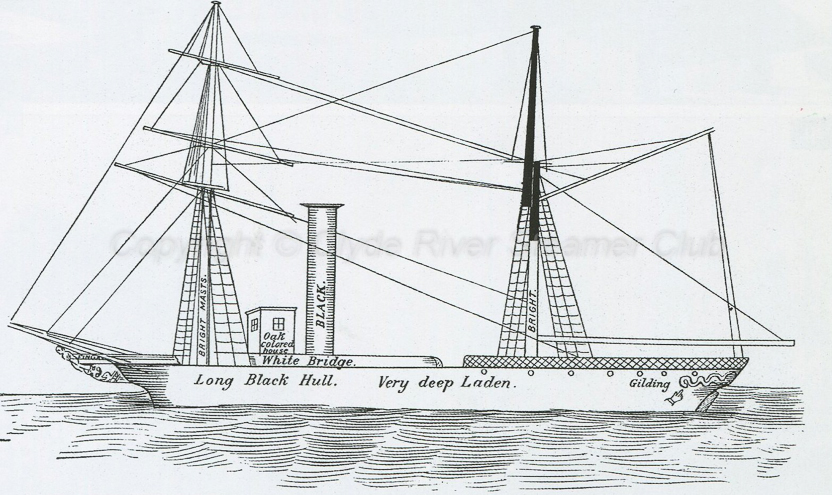

Fraser explained how, at the start of the Civil War, the north was ill-equipped to impose a blockade on the south’s 3,500-mile coastline. Of the union navy’s 26 steam vessels, only two were available to impose the blockade. We learnt of the tricks the Confederates played to camouflage the destination of their ship purchases in the UK. We also saw drawings of ships leaving Cork, sent to Washington by Federal agents to help identify likely blockade-runners.

A drawing sent by UK-based Federal agents

to help identify the Fingal on her arrival in the US

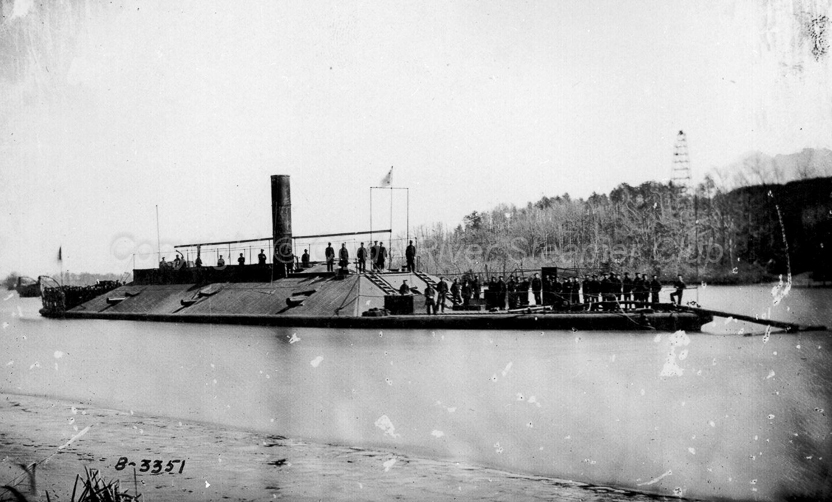

The Confederates used all kinds of subterfuge. The Fingal, the first ship to be sold for blockade-running, was advertised in October 1861 as leaving Glasgow for Madeira and the coast of Africa, but her “Bill of Entry” told the truth: she was heading across the Atlantic with a cargo including 11,240 rifles and 24,101 lbs of gunpowder — all of it intended for the Confederacy, though the destination was stated as Honduras. While her arrival was a morale-booster for the south, underlining how porous the blockade was in its early stages, the Fingal was converted to a warship but proved of little use to the south, or on capture, to the north.

The Fingal was renamed Atlanta

and converted for naval use

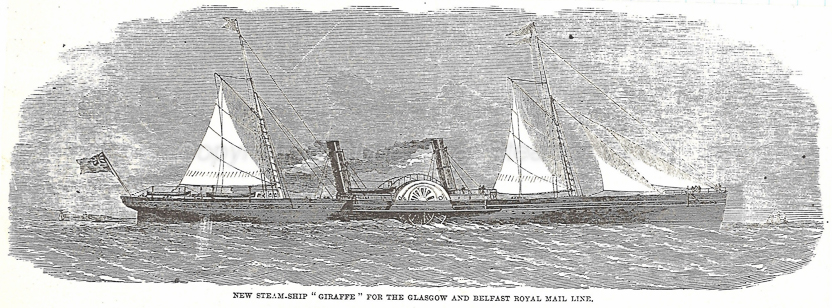

Once the blockade tightened, the Confederates took to transferring cargo at intermediate ports to smaller, faster blockade-runners that could avoid federal warships by sailing close to the shore — sometimes too close, as became obvious from an illustration showing the huge number of blockade-runners that were wrecked in the vicinity of Wilmington, North Carolina. Many of their skippers were former US navy officers whose first loyalty was to the south. One of the most successful was John Wilkinson, master of the Giraffe, who launched rockets as a decoy, sending his federal pursuers in the “wrong” direction. The Giraffe, renamed Robert E Lee after the legendary Confederate general, did 21 trips under Wilkinson’s command, before being captured on her first trip under a new skipper.

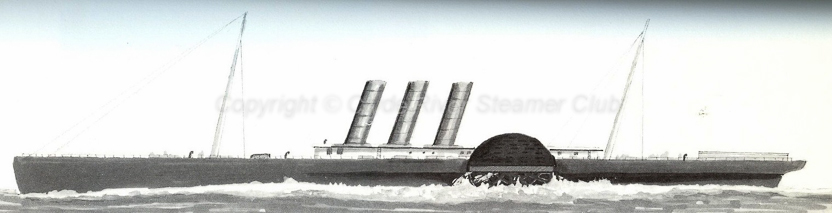

The Giraffe, built for the Greenock-Belfast trade,

was one of the most successful blockade runners

Fraser illustrated his talk, in part, by describing briefly the role of individuals caught up in different aspects of blockade running: John Wilkinson, mentioned above in connection with the Giraffe; Commander John Almy of the U.S.S. Connecticut, one of the Union ships enforcing the blockade; Warner Underwood, the long-suffering US Consul in Glasgow; and John Scott and Peter Denny, shipbuilders for several of the runners and who also invested in the business of blockade running through the Albion Trading Company.

Living conditions on the blockading ships were appalling. Crewmen could be at sea for a year, and Fraser quoted from one captain’s memoir, relating how he had awoken with a rat nibbling on his fingers and pulling at his hair. For Federal forces, capturing a blockade-runner was more lucrative than destroying it, for there was prize-money to be had. Half the value of a captured ship went to the government and five per cent to the squadron commander, with the rest going to the crew, of which the ship’s commander would receive 15 per cent. At a time when a sailor’s monthly wage was $14, a windfall of $71,000 — as received by Commander Almy — could set a skipper up for life.

A contemporary sketch shows Captain John Newland Maffit on the paddle-box

of the Glasgow-built blockade runner Lilian on 4 June 1864,

as she enters the Confederate port of Wilmington, unharmed by Federal pursuer

Clyde shipbuilders profited, too. Fraser recounted how at one point no fewer than 42 ships were being built by Clyde yards specifically for blockade-running, including the “Flamingo” class of shallow-draft paddlers, reputedly the fastest paddle steamers ever built. Denny built 20 blockade-runners, warships and privateers. In 1864 Scotts of Greenock built five 200-foot steamers for the Confederacy, four of which were lost on their first run (Scotts’ contribution to the Confederate cause was later wiped from the company’s official history).

The Flamingo and her sisters were considered by some to be among the finest blockade runners,

but they also suffered from chronic mechanical and structural problems

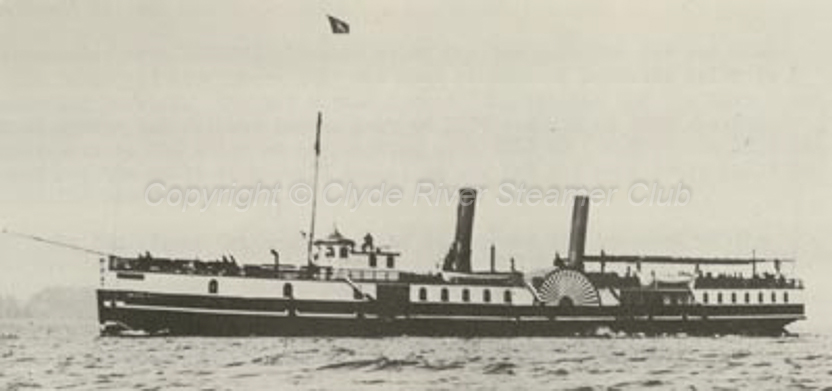

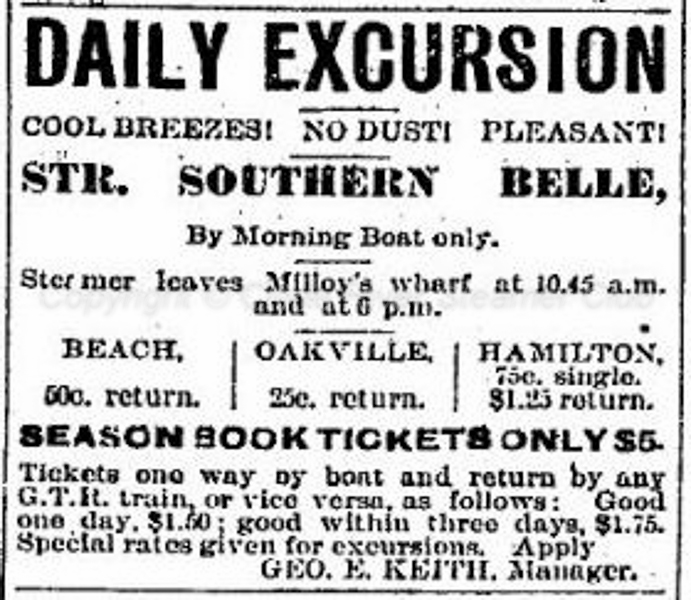

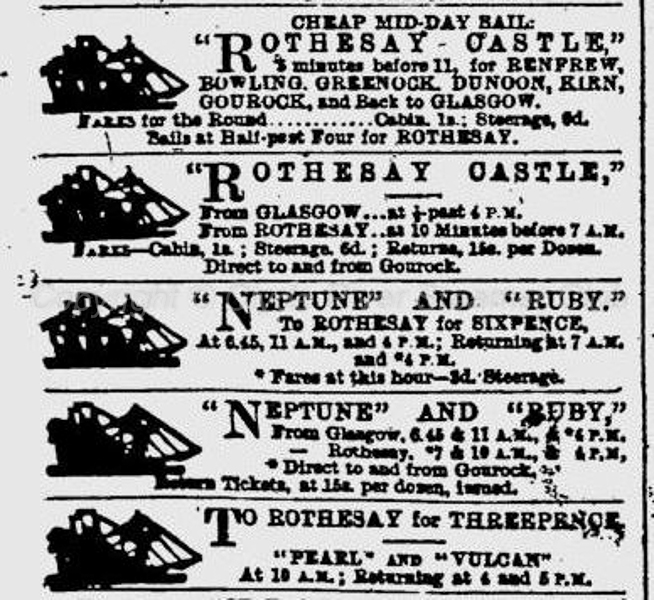

Two trips were enough to recoup building costs. The 1861 Neptune, reputedly the fastest Clyde steamer of her day, was captured on her third run after a 100-mile chase, but proved of little use to Federal forces as she was too slim to carry serious armaments. There was wry amusement when Fraser showed a Glasgow Herald advert from 30 June 1863, announcing that “The 7.30 Boat from Glasgow and the 11am from Rothesay is Discontinued for a few days” — an attempt to camouflage the fact that the Rothesay Castle had just been sold for blockade-running. She managed five runs from Nassau and had a successful career after the war, continuing in commercial service with a built-up superstructure until 1888, latterly at Ontario.

|

||

| A Glasgow newspaper advertisement of 7 July 1862 gives details of sailings by the Rothesay Castle, Neptune and Ruby — three Clyde ‘fliers’ that were quickly sold for blockade running |

One of her Great Lakes rivals, the Chicora, had also been a blockade-runner (as Let Her Be) and lasted until 1928. Many of the mariners running the blockade did well financially. Captain David Leslie retired at 38 and built several villas at Dunoon with names like Bermuda and Dixie.

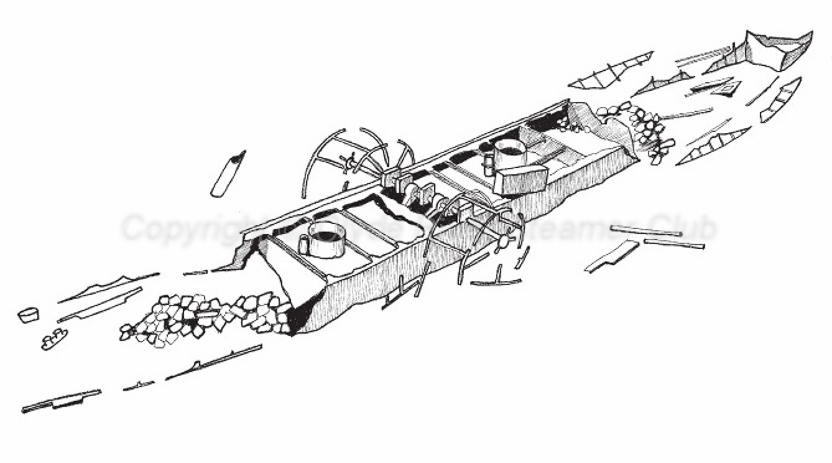

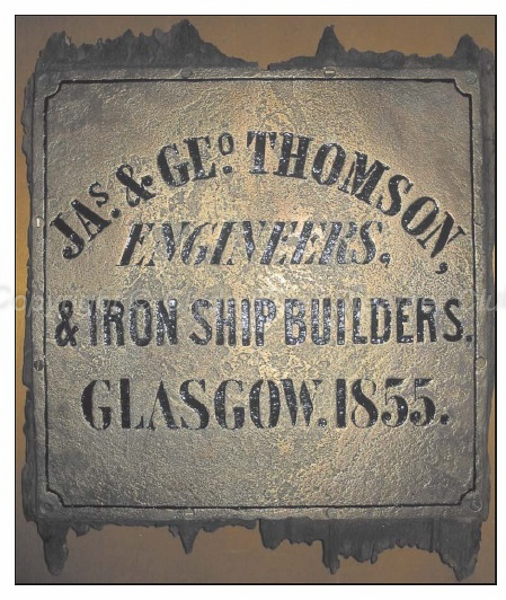

Another blockade-runner, the Mail, was captured twice: ships were sold on the open market and could be bought back by the Confederates. Some blockade-runners returned to the UK — two examples being the Sirius and Orion, both 1859 products of Cairds of Greenock (and better known as the Alice and Fannie at Stranraer and the Channel Islands). Others never made it across the Atlantic in the first place — the most notorious being the first Iona, wrecked off Fort Matilda as she was leaving the Clyde in October 1862. We were shown a diagram of her underwater remains and a photograph of her polished-up builder’s plate, rescued during a dive more than a century after her sinking.

|

|

|

| A marine archaeological survey identified these remains of the 1855 Iona off Fort Matilda on the Clyde |

Among the remains of the 1855 Iona brought to the surface was her builder’s plate |

Summing up, Fraser said estimates of the cotton that actually left the Confederacy vary greatly, but it is clear that the trade was only a fraction of the 1850s exports. Certainly the blockade, once effective, placed a major constraint on the purchasing ability of the Confederate agents in Europe. As far as the Clyde was concerned, while the American Civil War cost the Clyde many of its finest steamers, gold and sterling flowed into the pockets of the river’s ship owners and shipbuilders, resulting in the construction of a new breed of estuarial and cross-channel ships after hostilities ceased in 1865.

The talk ended with a short film from the Scottish Screen Archive of the Clyde steamer with which Fraser was most closely associated as an assistant purser in the early 1960s — the paddle steamer Caledonia. The vintage 1930s film can be accessed by clicking on the image below.

A ‘still’ from the Scottish Screen Archive film shows

the LMS sisters Caledonia and Mercury together at Wemyss Bay

In his vote of thanks Ian McCrorie explained that he had first met Fraser 54 years ago in a Maths class at Glasgow University. He saluted the depth and quality of research that had gone into the talk, and the accessible manner in which Fraser had presented it.

The October meeting was the first formal opportunity the Club had had to honour the memory of Gibbie Anderson, a past president, who died during the summer. Stuart Craig paid tribute to his friend, recounting how, as the CRSC’s first website convener, Gibbie would sometimes organise his holiday itinerary in a way that enabled him to turn up, unannounced, on the doorstep of distant enthusiasts with whom he had corresponded, thereby giving them a friendly connection with the Club. After this tribute, Gibbie’s brother Andy Anderson presented Stuart with a photographic memento of the 25 years of ferry- and island-hopping he had shared with Gibbie.

The meeting was chaired by CRSC president Deryk Docherty, who reminded members that the speaker at the next meeting, on November 13, would be Terry Sylvester, a key figure in the Waverley preservation story

For details of the CRSC’s full monthly programme of 2013-14 meetings, click here.