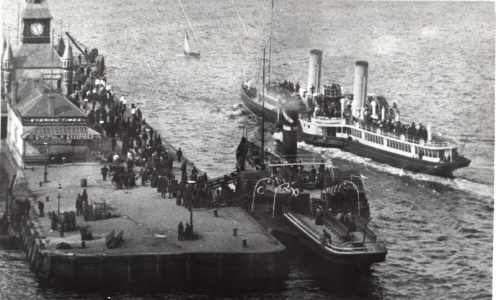

Pierside view of Ivanhoe c1904, showing the forward funnel’s steampipe (left). But this photo also reveals how easily Reid could have accosted Captain Williamson on the bridge. Copyright CRSC Archive Collection

Iain MacLeod uncovers an unusual incident in the working life of Captain James Williamson, one of the outstanding figures in Clyde steamer history.

If paddle steamer Ivanhoe has a special place in Clyde history it is because she set new standards in smartness, sobriety and good behaviour on board – so it comes as quite a shock to read Victorian newspaper headlines about ‘The Ivanhoe Assault Case’. It is even more surprising to learn that it was James Williamson, an almost legendary figure, who “assaulted” one of his passengers, a 62 year old engineer with a passion for yachting.

That passenger was Thomas Reid, who must have been looking forward to the day ahead as he stood on Dunoon pier just after 10.20 on the morning of Saturday 8 September 1884. Glancing north towards Kirn, he could see Ivanhoe’s black hull and twin yellow funnels gradually coming closer.

It was 32 years since Reid, a Paisley blacksmith, had set up his engineering workshop. The business had prospered and developed, and now he was able to leave its day-to-day affairs in the hands of his sons. With him on the pier were his wife, his daughters, a niece – and Jerry the Skye terrier. Sons Alexander and Thomas had joined Ivanhoe at Greenock.

This was the family party which that sunny September morning was expecting a pleasant sail in genteel surroundings through the Kyles to Arran. There was a slight breeze, so as the steamer headed towards Innellan Reid thoughtfully insisted that his wife and the other ladies should go below. He went with them to the saloon but then returned to check that they had left nothing behind. All was well, so he went below again – and to his surprise saw Jerry padding his way aft, all on his own.

And that was where the trouble started. Jerry had given Alexander the slip – the family knew that he was meant to be kept on deck – so Reid set off to take him back where he belonged. Before he could get away from the saloon entrance, though, he met a lady who politely told him that dogs were not allowed there.

He did not realise that this was Jane Fimister, the stewardess, and he was trying to make it clear that he was going to take Jerry away when she repeated her advice and then, to his astonishment, cried out “Mind what you’re about; don’t strike me”. Mrs Fimister – who was on her way up to see a rainbow – thought that Reid was so incensed at being told that he could not take Jerry into the saloon that he had lashed out at her. Reid could only imagine that, in the narrow passage, he might unintentionally have struck her while sweeping the dog up into his arms. He contended all along that he would be ashamed to strike a lady.

Mrs Fimister turned and spoke to “a man in a blue jacket”, the second cook James Robertson. Then she happened upon Angus McDougall, the Mate, and told him about a man “in a highly excited state, swinging and throwing his arms about and swearing”. “None of your damned tongue,” Reid had said to her. McDougall’s reaction was to take Reid by the coat collar and urge him to move to the forward end of the steamer – either to preserve the tranquillity of the saloon or because he thought that Reid was a steerage (third class) passenger and not entitled to be there.

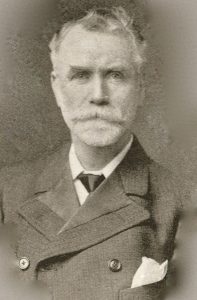

James Williamson — ship’s captain, steamer historian, innovator and manager, pictured later in his career as Caley Marine Superintendent

When Reid protested, he was “seized by some of the hands and hustled along the dark passage between engine and paddle box, stumbling on the paddle shaft”. He tried in vain to enlist the help of another passenger, and then the steward, a “yellow bilious-looking man” who was actually Jane Fimister’s husband, weighed in and accused him of making too much noise – at which point Alexander Reid joined in on his father’s side.

Leaving the commotion behind, Reid went on deck and complained to Captain James Williamson, who said that he would investigate. By now Ivanhoe was on her way to Wemyss Bay and after he had seen to the call there Williamson did go to speak to Mrs Fimister, the saloon steward and the second cook. What he heard was enough for him to tell Reid, when he returned to enquire, that he deserved all he got because he had struck the stewardess. Reid maintained that Williamson then threatened to have him kicked off the bridge.

After a further exchange with Williamson, this time in the saloon, Reid returned on deck as the steamer was approaching Rothesay and stood speaking to people he knew, including John Polson who made his fortune by inventing cornflour. He said that the topic was yachting, perhaps specifically Ayrshire Lass, Reid’s cutter; others saw Reid “moving himself up and down in a grotesque fashion” and concluded he must be “drunk or crazy”. Indeed, one of the Denny shipbuilding family was aboard and remarked that Reid was the first drunk man he had ever seen on Ivanhoe.

At Rothesay the purser twice asked Reid to go to speak to Williamson. He declined, saying that he had enough of Williamson and his crew, and all agree that he was then manhandled off the steamer. What was in dispute was the degree of roughness used and, crucially, whether James Williamson himself had ‘collared’ his noisy passenger.

Reid maintained that he had, and lost no time in seeking to have Williamson charged with assault: but the Rothesay Fiscal was on holiday and only seven or eight weeks later did he apparently suggest that it was a matter for the civil courts, not the criminal. In the meantime, Reid sought redress in another way: his lawyer wrote to Williamson asking for damages and an apology, neither of which he received. Now, in the Sheriff Court, he was asking for £250 in damages.

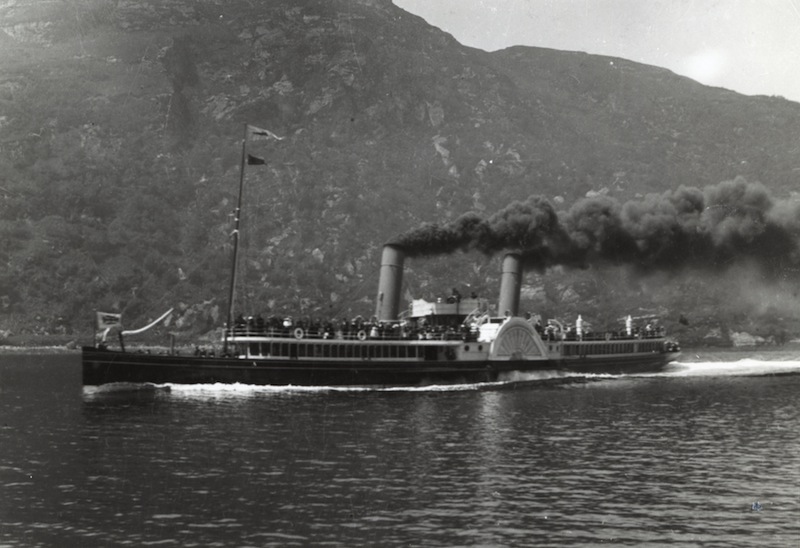

Ivanhoe slips past Benmore into the middle berth at Rothesay Pier c1885. Copyright CRSC Archive Collection

The Sheriff found in James Williamson’s favour and eventually, after an unsuccessful appeal, Reid agreed to pay expenses of £100. But the Sheriff also made it clear that adjudicating between two “men high in the estimation of their fellow citizens” was something he thought a jury should have done. He had no doubt that Reid had only hit Mrs Fimister by accident – but she was misled by his “rough and rude language and loud tones” into thinking that it had been a deliberate assault.

Unfortunately Reid had shown himself, even in the witness box, to be a “hasty, excitable, impulsive person” whereas Williamson had given his evidence “without the least appearance of excitement or exaggeration”. It was not because Reid had hurt Mrs Fimister that he was put ashore, but because in Captain Williamson’s view he was so “noisy and turbulent” that “his removal was necessary for the peace and good order of the ship”. The Sheriff did not doubt that there were “very sterling qualities below his somewhat rugged exterior” but his belief that Williamson “actively aided in putting him ashore” was “a pure delusion”.

Afterwards, there was sympathy for Thomas Reid and generous consolation. One July evening “a large and influential company of gentlemen” met in Paisley’s Globe Hotel to express their appreciation of his “manly character” and through Archibald Coats, the thread manufacturer, to present him with a cheque for £285, jewellery for his wife and a “highly-embellished address” speaking of his “genuine uprightness and honesty of character” and his “fearless contempt for anything which savoured of shams or meanness”.

Was Reid a man hard done by, his awkwardness and eccentricities and a loudness born of deafness misinterpreted by Ivanhoe’s officers and crew? That he was a man out of the ordinary was acknowledged by Williamson himself, who on that fateful morning noticed him at Dunoon, “walking about with his hat off, talking loudly” – and after his death the Scotsman remembered him as “a man of striking physique and very original and quaint in his observations”. A bully used to getting his own way, then, or a man clumsily keen to look after his family – and their dog?

And what of James Williamson, who spent several days in court as his actions and those of his crew were examined? He was a confident witness, sure of his ground: he had “never been brought up in this line before, though he had been hauled over the coals for racing and that sort of thing”.

“That sort of thing” had certainly got him into trouble before. Ten years earlier, for example, when he was just 24 years old and Master of his father’s steamer Sultana, he had found himself in the Greenock Police Court twice within a spell of six months. On the first occasion he had failed to slow his steamer as it passed the harbour, damaging a ship moored there and endangering life. Later he caused alarm by sailing Sultana between Vivid and Marquis of Bute to get the berth he wanted at Custom House Quay on a Monday morning, against the orders of the harbourmaster.

Williamson now wanted to put these trips to court behind him: they did not chime well with his status as Master of a steamer whose passengers were genteel and valued peace and order. So when he allowed “smoke in dense quantities” to billow from Ivanhoe’s funnels at Rothesay in June 1885 and was summoned to the Sheriff Court, he maintained he could not get a substitute to take command and sent the mate in his place.

In 1889, before he was 40, Williamson took on different and greater responsibilities, as pioneering Marine Superintendent of the Caledonian Steam Packet Company. Steamers still raced, but he was no longer on the bridge. The law could still reach him, though, and he did find himself in trouble again because of a bureaucratic oversight: Galatea sailed in mid April 1891 between Ardrossan and Arran and later in the month between Wemyss Bay and Rothesay without proper certificates on display, and the Sheriff decided that Williamson had to accept a greater share of the blame than the Master, Duncan Bell.

After Captain Bell appeared in court again in September 1894, accused of coming alongside Kirn pier in Galatea when Minerva had been signalled to go in first, James Williamson had a chance to make plain his feelings about the way steamer captains were treated. Perhaps thinking back ruefully to his own experiences he protested to an enquiry into pier signalling that the way steamer disputes were dealt with was “nothing short of a downright insult”. “Instead of captains being hauled to a Police Court and placed side by side with ‘drunks’ and other riff-raff” they should be handled by “experienced nautical men” or “a committee familiar with the working of this special traffic”.

Williamson had had his say, but it made no difference. Less than six months after his protest, on the evening of the Glasgow Spring Holiday 1895 a Board of Trade officer counted 1,619 passengers leaving Marchioness of Bute at Gourock as she came in from Dunoon and Kirn. Her certificate allowed just 1,119. The result? An appearance in the Police Court and a fine for Captain John Buie. A ship-handler of acknowledged skill and the Caledonian Company’s mastermind he may have been, but even James Williamson sometimes met his match.

Ivanhoe at Dunoon c1893, with a Buchanan steamer approaching from Kirn. Copyright CRSC Archive Collection

Ivanhoe sweeps out of Rothesay Bay c1900, overlooked by the Glenburn Hotel. Copyright CRSC Archive Collection

Catch up will all CRSC’s previous posts by clicking on News & Reports.