‘The Dooker’ on the bridge of Clansman: ‘There is commercial pressure all the time. That — and the paper work — is what makes the job onerous’

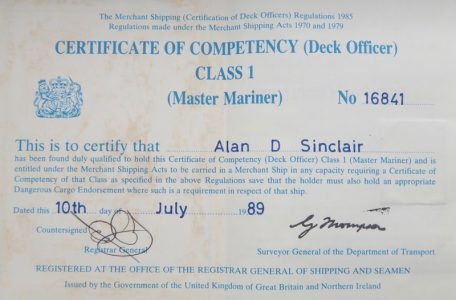

Captain Alan Sinclair is retiring from CalMac after 32 years’ service, during which he earned a reputation as one of the company’s finest ship handlers.

Known throughout the fleet as ‘The Dooker’, a nickname associated with his Tarbert (Loch Fyne) background, Captain Sinclair bowed out this month with an open email to staff in which he made clear his frustration with CalMac’s management culture and west coast infrastructure — views widely shared by fellow officers but unlikely to endear him to Managing Director Robbie Drummond, who issued a curt riposte.

In the quiet of his Lochgilphead home, Alan Sinclair talks to CRSC’s Andrew Clark about micromanagement, misalignment of piers and the matching of ships’ lengths to Hebridean wave patterns.

Anyone who has observed Alan Sinclair at work knows not only that he is a born ship handler, ‘driving’ a ferry with dazzling skill, but also that — by his own admission — he is “not renowned for keeping my mouth shut when something needs to be said.”

Captain Sinclair lived up to his reputation this month, raising eyebrows throughout the fleet with a candid farewell message that lifted the lid on what many of his colleagues were thinking but would be reluctant to express openly. In essence, he wants managers to show more trust in seagoing staff, and ferry and harbour infrastructure to be put in the hands of people with proven experience of the territory.

The sheer honesty of his email ‘rant’ (his word) raised eyebrows in some circles but smiles from many colleagues, who respect him for his experience, admire him for his easy style of command (one hand in pocket, the other on the bridge controls) and speak fondly of his loquacious conversation.

Alan Sinclair has long stood out among senior colleagues, not so much for his forthright views as for his versatility. As one of CalMac’s senior relief masters, he has never been tied to a single ship or route for any length of time — the advantage being that he gained an almost unrivalled familiarity with the quirks of virtually every wheelhouse and harbour in the CalMac domain.

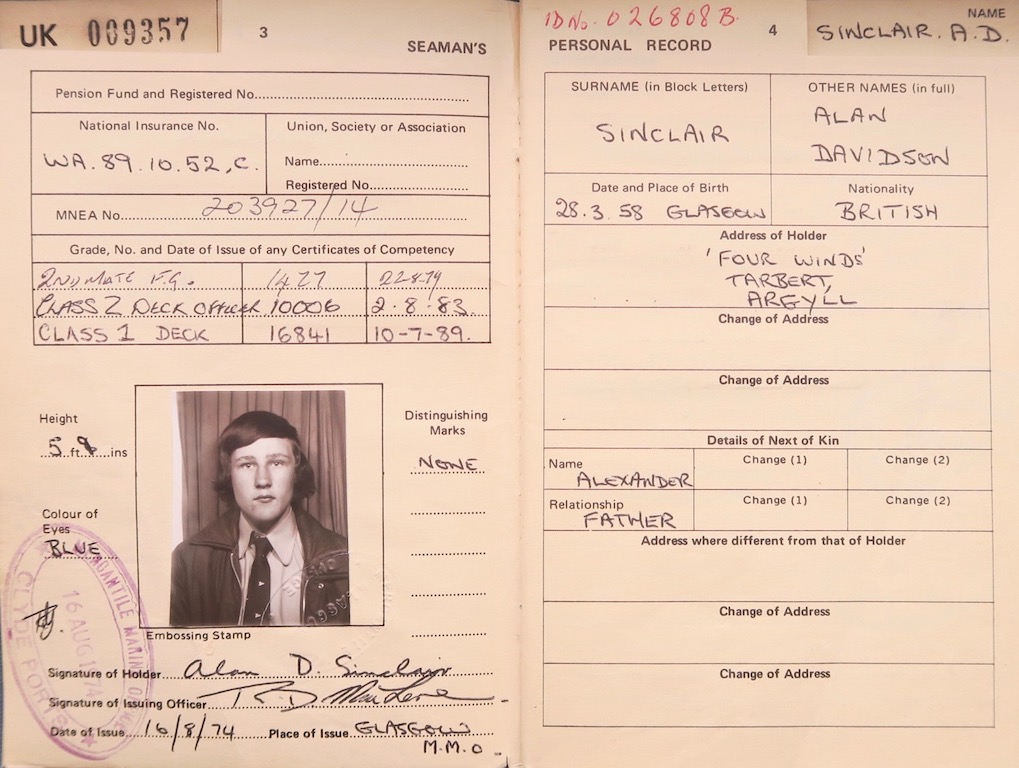

The son of a technical teacher who was a carpenter by trade, the young Alan would accompany his father on the family motor cruiser to destinations as far apart as Stornoway and the Isle of Man. “We had an affinity: I learnt the basics of seagoing from him at an early age,” he says. “I didn’t ‘decide’ to go to sea — it never occurred to me to do anything else. Dad originally wanted to go to sea but was partially colour blind, so he could never have held a certificate of competency. I basically did what he had wanted to do.”

From his father he inherited his handyman skills, of which there is plentiful evidence in the backyard of his Lochgilphead home, and his Tarbert background gave him a distinctive nickname, ‘The Dooker’. A dooker, he explains, is a black and white guillemot that ‘dooks’ under the water. Long ago, probably through an association with the Tarbert fishing fleet, it became the name for anyone hailing from the Loch Fyne port. And so, whenever ‘The Dooker’ was mentioned in CalMac circles, everyone knew who was being talked about.

Born on 28 March 1958, ‘The Dooker’ went to sea in 1974 as a Denholms cadet, and spent the next four years either roaming the world on all sizes of ship up to 264,000 tons, or studying in Plymouth and Glasgow for his certificates. He continued with Denholms for another seven years as third mate — a period that taught him “how to look at different points of view, not to jump to conclusions and not let little things get out of proportion.”

He also learnt something about onboard discipline: “In those days, anything inappropriate was dealt with by colleagues — they would soon tell you. It didn’t require a ‘big brother’ approach, whereas now managers think they’re running the show and it’s up to them to be some sort of police force. That’s one of the reasons why [aged 61] I’m not hanging about.”

He says the mandatory introduction of the International Safety Management Code (ISM) in 2002, following the Herald of Free Enterprise and Estonia disasters, rectified previous slackness in safety administration, but fostered a climate of suffocating over-regulation. “In the past we were trusted to do the job we were qualified for and allowed to get on with it. ISM has regulated it to the point where everything has to be written down as a procedure, inadvertently fostering a blame culture.

“It tries to standardise behaviour in an environment where there are an awful lot of variables. Managers keep saying ‘the master is still in charge’, but they’re very quick to wave the red card if the outcome isn’t to their liking. If, for example, there is a mechanical failure during a berthing and the ship hits the quay, they’ll jump on anything that can be blamed on you after the event. ‘We’ve made all these procedures to stop things going wrong, so it must have been your fault.’ But these things happen in a very fluid situation. A master can only do his best. With hindsight it’s always easy to pick holes.”

‘She cavitated like hell, but she was fast, with old-fashioned propellers that worked like a mincing machine. Once she was off, she moved like a scalded cat’ — Glen Sannox manoeuvring at Ardrossan. Copyright CRSC Iain MacArthur Collection

It was different in 1987 when, after deciding he had seen enough of the world, the 29-year old Alan Sinclair joined CalMac. His first posting — as second mate, because at that time the company had no third mates — was to Glen Sannox on the Mull and Colonsay service. “Back then there were no ‘hours of rest’ problems: the length of working day was realistic, so you had a master, a mate and a second, and a Chief Engineer and a second, and that was all you required to complete the day.”

The wheelhouse on the ‘Sannox’ was “not much bigger than an outside toilet — all it had was a telemotor with brass steering pedestal and lots of springs and levers, with a wheel attached. The radar was like something out of the Ark. I thought ‘what have I done?’ After deep sea, it was like going back to Para Handy. The second mate’s cabin was a box, welded onto the end of the bridge deck, with a wooden deckhead that leaked: to get to the toilet, you had to step into the open and go down a deck. ‘Primitive’ was not the word, but you quickly adapted.”

As to performance, Glen Sannox had no stabilisers, limiting the routes on which she could operate, “but she was fast, with old-fashioned props that worked like a mincing machine. She cavitated like hell [a process which creates air pockets around the propellers, reducing their effectiveness], but once she was off, she moved like a scalded cat.”

He also served on the “stylish, almost stately” Columba (now Hebridean Princess), sailing to Tobermory, Coll, Tiree and Iona. The master was Hugh Sinclair, renowned for unflappability. “We had very few crisis situations in those days. We seem to have more now.”

Pioneer was another of the older ferries on which Alan Sinclair worked. She was widely loved, he recalls, “but she was not the best bit of planning. They bought her half-built as a supply boat and changed the upperworks. The trouble is, they also added a hoist, because very few of the piers back then had linkspans. This left her with a deadweight of 65 tons, so all she could carry was a lorry and 20 cars. In those days we didn’t have the commercial traffic we have today, and she always got them out of trouble: she could respond to any emergency.”

Captain Sinclair gained his master’s ticket in 1989, but had to wait until 1998 for his first command — a brief spell on Pentalina B (the former Iona, chartered back from Pentland Ferries to assist at Oban-Craignure), quickly followed by Lochmor. For most of his CalMac career, however, ‘The Dooker’ has not been associated with any one boat. He spent eight years alternating between Hebridean Isles and Lord of the Isles as ‘third master’, before taking on the job of relief master in 2011, getting to know just about every major unit of the fleet. His final command was Isle of Mull.

His favourite is the oldest — Isle of Arran, “the last ferry to have been built with proper looking funnels,” he says. “It’s unfortunate that most modern funnels look like Corn Flakes packets. There was character and style in the older boats. If something breaks down with the newer ones, you have to send for an expert from the other side of the world. With the ‘Arran’, you can just swear at it with a hammer. I’m not keen on so-called ‘state of the art’ electronics or touch screens — not because I’m a dinosaur, but because the latest systems don’t always work, and they usually decide not to work at the worst possible moments, when you really need it to do what you want it to do.”

It may be no surprise, then, to hear that his least favourite ship is one of the most modern — Finlaggan. Captain Sinclair dislikes the internal layout and high gloss decor, which he describes as “tacky”. More importantly, “she’s highly skewed in the twist of the [propeller] blade from the root to the tip. This may be desirable with traditional propellers, but with controllable pitch propellers it reduces astern power — a critical factor at Port Ellen, where there’s no sea room to turn. The slower you go in, the more prone you are to drift due to the wind. You have to be able to stop quickly and turn on the spot, which would work well if you had a handbrake, but Finlaggan has extremely slow controls. The company have been reluctant to address this.”

He is much more positive about Lord of the Isles, which he describes as “fit for purpose. She is a reliable and consistent boat to handle. Like the old Hebrides and Columba, she is very effective at what she does, due to a combination of equipment and design. Her power — the engines and bow thrust — is adequate and evenly matched between the two ends of the boat, and the windage is also balanced: you can predict very accurately what she is capable of.”

Her one drawback, he says, is that she is “an awful sea boat. She can perform three different movements at one time, leaving you confused as to where she has gone.”

This brings us to the subject of ferry design. Captain Sinclair says the general level of swell on Scotland’s west coast is such that any boat with a length of about 80 metres “will fall right into the bottom of every trough. At 85 metres LOTI has a tendency to land in the face of the next wave with a bang: you lose speed considerably, which makes the stabilisers less effective because you’re going slower.

“Lengthening Isle of Mull by five metres [within a year of her December 1987 launch] made a stunning difference: the slight increase in length means that instead of pitching right into the bottom of every hole, she rides it better. She has a sort of ‘sponson’ aft to improve stability and buoyancy, but she is now more inclined to broach in a following sea, which picks up the stern and carries it sideways. LOTI’s designers could have learnt from that. They made her boxy and stiff, which affected her seakeeping. They used to say that LOTI in a sea was like doing all the rides at Alton Towers rolled into one, but cheaper.”

Within the generally accepted measures of stability and how a CalMac ferry responds to the sea, he sees the two extremes as ‘stiffness’ (Lord of the Isles) and ‘tenderness’ (Isle of Mull), “and there’s a happy medium that we rarely hit.” At 98 metres, Clansman and Hebrides fall into that category, “more by good luck than by design. Getting a happy medium isn’t what most ship designers aim for: their goal is getting the boat to carry the amount of cargo that is desired by the owner.”

Captain Sinclair’s views on Clyde and Hebridean piers are equally nuanced. Coll, he says, is susceptible to a surge in the bay. “It makes it impossible to keep the boat still when you are alongside the pier — she goes back and forwards like a road roller. Tiree is probably worse, because of its exposure to swell from the south and east. All single-sided piers are a problem, especially when the prevailing wind is off them. It makes berthing difficult, and it’s almost impossible to lie alongside for any length of time [in anything above moderate winds]. What it really needs is a breakwater, but the general attitude is “the Lord never built it like that so we’re not allowed to change it.” Anywhere else in the world they’d create a harbour where they wanted it. We’re stuck to what was built in the dark ages for puffers to dry out alongside.”

Even where a new pier has been built, as at Brodick, “it’s not very good, because it’s a hollow pier and provides no shelter — it’s very exposed to easterly winds and swell.”

And Ardrossan? The harbour’s exposure to southerly winds and swell at the entrance makes it notoriously difficult to get into when the prevailing wind is anything more than moderate. Although CalMac masters are versed in the ‘do I abort?’ dilemma, Captain Sinclair believes Ardrossan is the one port where the question should never need to be asked.

“Ardrossan requires a level of experience so that you make the decision at Brodick — you make a decision not to go anywhere near it. ‘Going to have a look’ is not one of my favourite pastimes. As a general rule, if you’re not sure you can manage it with a reasonable safety margin, you shouldn’t be trying. You frequently get the suggestion — ‘can you not go and have a look?’. What managers want is to be able to say to the public that ‘we tried’. There is commercial pressure all the time. That — and the paperwork — is what makes the job onerous.”

Captain Sinclair’s valedictory email to colleagues included sentiments directed not just at CalMac’s Gourock management but also CMAL and public policymakers. “We need to be planning piers that will accommodate a five-metre draught, and we need to be doing it 10 years ago, not 10 years from now — preferably solid, double sided piers with a linkspan on both sides; marshalling areas for more than the ship’s capacity; departure lounges/waiting areas equivalent to the ship’s capacity. Then we need to be building a suitable fleet for the future. A deeper draughted ship would give increased deadweight, better seakeeping and increased propeller and bow thrust immersion, resulting in improved handling and fuel efficiency.

“All the management and information technology in the world is not going to make wrong infrastructure right, especially when most of that management is recent, and now has no direct knowledge of our service.”

But are the views of one CalMac master going to make a difference? As he contemplates a life in retirement, ‘The Dooker’ needs no one to tell him the answer.

All photographs on this website are protected by copyright law. Please do not reproduce them without first asking permission from info@crsc.org.uk

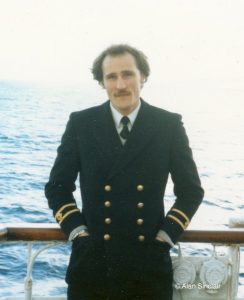

Captain Sinclair was a rare example of a CalMac master who regularly wore his officer’s jacket on the bridge

Finale on Isle of Mull: at the end of his last shift for CalMac in June 2019, Captain Sinclair (right) bids farewell to (from left) 3rd officer Alex Gray, 2nd officer Ray Summers and Captain Lewis Mackenzie

A specially inscribed quaich presented to Captain Sinclair by the crew of Isle of Mull in June 2019 as a mark of their esteem

Published on 28 June 2019