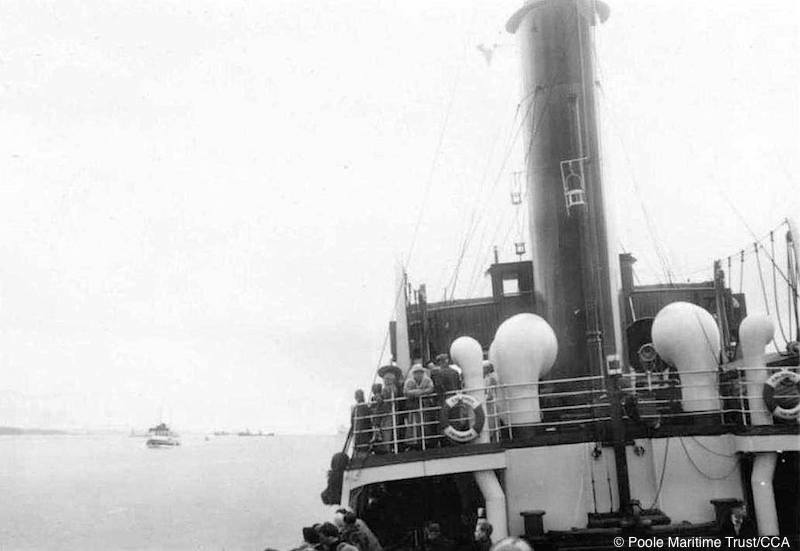

With a passenger capacity of 566, Calshot (right) was useful as a ferry and a tug-tender. She is seen here at Southampton’s Western Docks in the early 1960s, before she was sold to Ireland

Richard Coton sounds the alert for a former Clyde tender, now threatened with demolition, and recalls a journey on her 50 years ago to the Aran Islands on the west coast of Ireland.

There has been good news in recent weeks about the level of support for Waverley’s boiler appeal and Queen Mary’s static preservation, but another former Clyde passenger steamer, the tug-tender Calshot, is facing a much bleaker future. Indeed, 90 years after her launch, attempts to preserve her seem to have come to the end of the line and she is likely to be broken up.

Despite Clyde passenger steamers being responsible for most of the tendering to liners at the Tail o’ the Bank, there were also specialist tug-tenders like the famous TSS Paladin (1913), belonging to the Anchor Line and latterly to the Clyde Shipping Company Ltd. My father recollects her as running mainly from Princes Pier, and being remarkable for the excessive height of her funnel. Tenders like Paladin were used on the Clyde, at Plymouth, on the Solent and elsewhere. Their 1st class accommodation was generally high quality, suitable for passengers accustomed to transatlantic luxury, though steerage accommodation was correspondently basic.

Small ship, big funnel: Calshot in the 1950s at Southampton with Cunard’s Clyde-built Queen Elizabeth

The most famous tender of all was TSS Nomadic, built alongside Titanic at Belfast in 1911. Owned and operated by the White Star Line, she was designed to ferry passengers out from Cherbourg to Titanic and her sisters. Some of the last doomed passengers to join Titanic did so across the decks of Nomadic on 10 April 1912. Remarkably, Nomadic remained in her original role at Cherbourg until 1969. She is now superbly preserved in dry dock at Belfast.

Paladin is long gone but, remarkably, her former wartime consort on the Clyde is still with us — though her future hangs by a thread. Launched in 1929 at J. I. Thorneycroft’s shipyard at Woolston, Southampton, TSS Calshot (684 gross tons, 147ft x 33.1ft) had been designed to ferry passengers from liners anchored in Cowes Roads (the Solent’s equivalent of the Tail o’ the Bank) to Southampton Docks. In her heyday she numbered among her passengers Hollywood stars such as Elizabeth Taylor, Charlton Heston, Bob Hope and Ginger Rogers, and politicians like Winston Churchill. She was a powerful and well-designed steamer with twin steam reciprocating engines. With a capacity of 566 passengers, she was also pressed into service when required on the Isle of Wight ferry service and even for excursions.

What made Anchor Line’s Paladin on the Clyde and Red Funnel’s Calshot on the Solent particularly useful, however, was that they – unlike Nomadic — were a curious hybrid of passenger tender and powerful steam tug. World War II saw weekly arrivals at the Tail o’ the Bank of numerous troop ships including the two giant Cunarders, Queen Mary and Queen Elizabeth, carrying thousands of American soldiers to Europe. Suddenly more tenders to ferry the troops ashore were needed. And if a tender could be found that was also a powerful tug, so much the better.

Calshot was requisitioned early in the war and sent north to Scapa Flow as a tender for Royal Navy warships. She was also equipped as a salvage tug, and during that time was sent to salvage a U-Boat beached on the Scottish coast after being attacked by the Royal Navy. It was apparently quite a gory sight.

When the troopships started to arrive on the Clyde from the United States in 1942, Calshot was hurriedly brought round from Scapa Flow and based at Gourock. Between 1942 and 1944 she proved a considerable asset on the Clyde, ferrying thousands of troops ashore to Gourock Pier — as well as celebrities like Winston Churchill. In 1944 she was sent south again to assist with D-Day. On her departure, the Clyde Admiralty Berthing Officer sent a letter of thanks to Captain Chisman and his crew: “It did not take long to find that the Calshot could be depended upon to do anything at any time, and do it efficiently, thereby giving complete satisfaction at all times. My best wishes go with you in your new sphere of activities, knowing well that whatever your particular job may be, the Calshot can be depended upon to give her best.”

Calshot was equally valuable to the war effort in the English Channel, towing sections of the Mulberry Harbour over to France and serving as a Headquarters ship at Juno Beach.

After the war she was joined at Southampton by her former Clyde running mate Paladin, Red Funnel having quickly snapped her up when she was no long needed at the Tail o’ the Bank. The veteran Paladin lasted at Southampton until 1960, when she was scrapped. Calshot continued with Red Funnel for another four years.

When replaced, however, she was quickly acquired by Port and Liner Services (Ireland) Ltd, a subsidiary of the Limerick Steamship Company, and renamed Galway Bay. The installation of new diesel engines allowed her funnel to be reduced in height, but she was otherwise completely unaltered. Sailing as a successful excursion steamer in the west of Ireland until 1985, she was then inspected by Waverley Excursions Ltd to determine if she was suitable for the Bristol Channel. They opted for Balmoral instead, and Calshot — now back with her original name — was bought in 1986 for static preservation the City Council at Southampton, her former home port.

Nine years later ownership passed to the Tug Tender Calshot Trust. In 2008 her funnel (her most distinctive feature as a tug-tender) was restored to its original 30ft height.

Her engines are still fully operational, and are fired up from time to time. An engineer enthusiast has spent about £32,000 of his own money maintaining them. She remains beautiful internally, and looks considerably better than she did when I sailed on her in Ireland 50 years ago. The hull, however, may not be so sound and looks pretty dilapidated.

Although Calshot was provided with a free berth in Southampton for many years by Associated British Ports, she never seemed to attract enough visitors to be a viable financial proposition.

Her berth is now required for redevelopment, and the Calshot Trust have failed to find an alternative. An offer to sell her for £1 produced no viable buyer and so the Trust have issued a ‘notice to deconstruct’. Unless a ‘guardian angel’ can be found over the next few months to keep her intact, she is likely to be slowly demolished.

* * * * *

Richard continues: While sorting through some old papers recently, I was amazed to find notes I had written in 1969, when I was fortunate enough to make a memorable voyage on Galway Bay ex Calshot in the west of Ireland. I was busy preparing for university at the time, so I must simply have forgotten about the draft article. Here it is, only 50 years late!

TO THE ARAN ISLANDS ON TSMV GALWAY BAY

When she was bought in 1964, the aim was to use Galway Bay for tendering the liners of the Holland America Line and also for day cruises to the Aran Islands, at the mouth of Galway Bay. In 1968, however, the liners ceased to call, and in 1969 the Limerick SS Co chartered the ship to the Irish Transport Board. She is now exclusively running excursions to the Aran Islands, and the day return fare has increased to 40 shillings.

Galway Bay normally leaves her home port in the morning or early afternoon according to the tide, on every day except Thursday. The sail, of about two and half hours, is pleasant on a fine day, although the course lies out into the centre of the deep bay, and the only points of note on the journey are the severe, stony crest of Black Head and, beyond that to the south, the distant cliffs of Moher.

Outside the bay, as the vessel sails westward, the Atlantic swell provides a lift to the decks on even the calmest days. Two of the three Aran Isles may be seen to port, but the ship’s course lies towards the largest and most westerly island, Inishmore, which is also the furthest north. Its long, grey hump is seen ahead, and after passing the brilliantly white lighthouse on the island at the bay’s mouth, Galway Bay moors at the island’s only pier at the village of Kiloran.

A line of ponies and traps awaits our arrival, offering tours of the island. There are virtually no cars (and certainly no buses). Wood is very scarce, so the stone-walled fields lack gates; the wall is simply breached to take animals in and out of the field, and then rapidly rebuilt. Massive cliffs on the western side of the island tower more than 300 feet above the Atlantic breakers.

The islanders speak very little English (Gaelic is used everywhere), and everything gives us the feeling that we are in a completely different land, right at the edge of the world. Between 3½ and 6 hours are allowed ashore, before a return in the early evening, normally at 6 or 7pm.

The ship herself is interesting, but is only a pleasant sail in good weather. A squat funnel and diesel engines installed in 1964 proclaim her to be a modern vessel (as, curiously, does the date of 1964 on her bell). The plaque below the bridge, however, announces that this is none other than Ship No. 1093, built in 1930 by John I. Thorneycroft & Co Ltd, Engineers and Shipbuilders, Southampton.

The accommodation, unfortunately, has not been updated since the builder’s plaque was installed. A broad companionway leads from the wooden seated deck shelter to the lounge. From this, a companionway of equally remarkable breadth (built to accommodate liner passengers) leads to the bar.

Safety regulations demand that all headlights on these decks remain closed during the passage, giving a claustrophobic effect. This is certainly not helped by faded panelling and upholstery and neglected paintwork. Extensive crew accommodation occupies the lower deck to the rear of the engines (formerly the austere covered space for liners’ steerage passengers). Finally, the advertised ‘full catering facilities’ turn out to be no more than a kiosk in the deck shelter which sells coffee and sandwiches, and an ample bar on the lower deck.

Little, in fact, seems to have changed from her days as Calshot. The towing hook and the bow fender are still in position, as is a notice warning the towing crews not to smoke or use naked lights. There is also a puzzling notice at the top of the companionway, which announces that the saloons are for the use of ‘Passengers and Officials Only’. In her current role, does she sometimes carry livestock?

* * * * *

The notes for my 1969 article are unfinished and end rather abruptly. I do remember that it was a most enjoyable day: those Aran Islands were quite magical, with their ponies and traps, their fields without gates, and everyone speaking Gaelic. On our return voyage, there was quite a heat haze as Galway Bay slipped gently through waters that were oily-calm. The vessel was not exactly fast, so conditions on deck were balmy. We relaxed in the warmth on deckchairs which would not have looked out of place on Aquitania or Queen Elizabeth.

Galway Bay’s fittings and décor may have been faded but they were exactly as they had been when she tendered the grand liners of the 1930s. Her mahogany and oak paneling was still magnificent, and she had beautiful arched internal doors that would not have looked out of place on Titanic. It really did feel as though we had been transported mysteriously back in time.

In some ways, Calshot’s history has come full circle. This fine steamer served the ocean leviathans of yesteryear on the Clyde and the Solent. Her berth in Southampton is now required for redevelopment as an ‘ocean terminal’ for the benefit of the leviathans of tomorrow. It will be a great pity if, having survived this far, Calshot is broken up for want of a new home.

Calshot’s funnel being restored to its original 30ft height by Vosper Thorneycroft on 18 September 2008

Calshot’s engine room telegraphs are among the many original features that have survived since her days on the Clyde as a tender during the Second World War. Unless a ‘guardian angel’ can be found over the next few months to keep her intact, the ship is likely to be slowly demolished

Given Calshot’s red-and-black funnel and traditional features, you could well mistake her for a Scottish ship — and she did serve on the Clyde during the dark days of war. Can she be saved?

Also by Richard Coton:

Family tradition and Aunt Lucy

Published on 19 August 2019