Varnish and polish: view aft from the foredeck of Kingswear Castle, showing the engine window in front of the wheelhouse — copyright photo Robin Copland

Like most ship enthusiasts who have visited the River Dart in Devon, Robin Copland was astonished by the richness of the ‘Kingswear Castle experience’. Fresh from a 90-minute harbour cruise at Dartmouth, he records his impressions of a paddler that entered service more than 90 years ago.

Somebody once said that a ship is only as good as the people that serve on her. Kingswear Castle is a lucky ship if that is the case, because her crew is dedicated to her; to her upkeep and to her success on the river for which she was built and to which she has returned after a long time away.

We found ourselves in Dartmouth for our son’s ‘passing-out’ parade at the Britannia Royal Naval College. The college has been located in Dartmouth for well over a hundred years, first as an ex ‘ship of the line’ anchored in the harbour, and then as a brick college building that overlooks the town and its harbour. We decided (well actually, I had planned this all along!) to take the chance to have an afternoon sail round the harbour.

Robin and Lois Copland were in Dartmouth to attend their son Ian’s ‘passing-out’ parade at Britannia Royal Naval College — copyright photo Robin Copland

Dartmouth’s landing stage is conveniently located in the centre of the old town and is in essence a floating pontoon, with an access pier from the harbour wall that rises or lowers depending on the state of the tide. This simplifies the embarkation process, with no need for the gangplanks that we know and love on the Clyde. Instead, a short ramp does the job, no matter what ship is alongside.

You can purchase tickets for your sail in advance on the web or from little vendor huts around the pier. Our 90-minute harbour cruise cost £8.50, but there are all kinds of rail and ship packages for those wishing to combine a paddle steamer trip with a ride on the similarly preserved Kingswear to Paignton steam railway: the two are jointly promoted by the Dartmouth Steam Railway and River Boat Company.

The pier is one of the focal points of the old town. It serves as the Dartmouth terminal for the regular two-ship passenger ferry service to Kingswear across the river, as well as being the main pier for all cruises given by a fleet of motor vessels (run by the same company). Kingswear Castle is a member of that fleet, albeit a special one, and her cruises command a slightly higher price than those offered by her fleetmates.

She fetched up tidily against the landing stage with a minimum of fuss. As you walk along the pontoon, you notice the gleaming hull, the decorated paddle box and the sponson that runs almost the length of the ship. As you step aboard, you are leaving behind the fast-paced world of the 21st century to enter a gentler age.

The first impression is of wood — everywhere. The bridge, the deckhouses, the stairwell coverings, the seats — all are polished wood. The seats are covered with bench cushions for warmth and comfort. A green tarpaulin encloses the main deck aft of the bridge to protect patrons from the odd passing shower. The decks are traditional teak and, to be honest, you could happily eat off them.

That’s the next thing that strikes you. Kingswear Castle is remarkably clean and cared for. All of the wood is varnished and polished; all of the brass fittings likewise. Wherever you go, wherever you look, it is as if she has just returned from a massive spring clean — even at the end of a long season.

Her crew are all smartly turned out in what you might almost describe as yachtsmen’s uniforms. Creased shirts, tailored shorts, long socks and shoes — all clean! At one point, I looked down into the boiler room where, as you can imagine, they spend a fair bit of time shovelling coal. It was clean, for goodness sake!

I went, as is my wont, for a wee ‘explore’. Towards the bow, hardier souls can sit with the wind in their hair. You look back to the bridge and forward to the nicely raked ‘v’ of the bow.

Just in front of the bridge, there is a viewing window through which you can see the engines. Down some stairs there is a small saloon where you can buy tea, coffee and refreshments. I fell into conversation with the steward, a South African, and you could tell that he loved his work and his charge. He had been on board for two years and had resisted any suggestions of working elsewhere. He just liked what he did and that was that. Same with the engineer who, it turned out, normally worked in the office but was doing his turn in the engine room. Same for the purser. Same for the captain, who spent his spare time in the winter varnishing and polishing. This wasn’t a job for these guys; this was where they wanted to be.

Towards the stern of the ship, and past the door looking down to the boiler room, there is another set of stairs leading to a carpeted saloon where a small historical exhibition tells the ship’s story.

And then there were the noises. The wee groans and whistles; the snoring and snorts of a living engine doing the job for which it was designed and built 110 years ago; from the bowels of the ship the grate of shovel on coal; that lovely, throaty sound of her steam whistle; the splish-splash of the paddles — gentler and less frantic than Waverley’s — as she took us out of the main harbour to the estuary, with Dartmouth Castle brooding to starboard and the town of Kingswear to port.

A gentle turn through 180 degrees and we paddled back towards the main harbour, with splendid views of the Naval College on the hill above the old town to our left and a departing steam train on our right. Yachts everywhere; the odd picket boat sailing busily past with naval college students on board learning the rules of the road; the eccentric ‘lower ferry’ — two floating pontoons pushed and pulled by tugs back and forth with their loads of cars and foot passengers.

We sailed past the pontoon where we had earlier embarked and on up the river to the Higher Ferry, a relatively new cable-driven vessel, though she does have thrusters at each corner to help her manoeuvre in the strong tidal conditions of the estuary. And on past Kingswear Castle’s birthplace, Philip and Son of Dartmouth. The building still stands, though the yard closed years ago.

Our ship — the last remaining coal-fired paddle steamer in operation in the UK — was built here in 1924 (her engine is even older, dating back to 1904). She was designed for humble ferry work and served on the Totnes to Dartmouth run for 40-odd years. For the size of her, it is amazing to consider she could carry almost 500 passengers in her heyday.

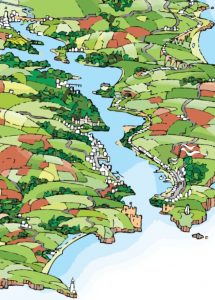

The Dart estuary in south Devon, with Dartmouth on the lower left, Kingswear on the lower right and Totnes at the head

For anyone lucky enough to take a sail on her, Kingswear Castle comes across as a piece of living history. She was actually one of a fleet of three paddle steamers built for service on the Dart. The oldest, Compton Castle of 1914, was withdrawn in 1962 and became a floating restaurant at Kingsbridge before being moved to Truro, where you can still find her hull. Totnes Castle, built in 1923 and withdrawn in 1964, sank in 1967 while being towed to Plymouth; her bell survives in Totnes Museum.

During the Second World War, Kingswear Castle was lent to the US Navy for use as a harbour tender. She returned to peacetime service at the close of hostilities and remained in service until 1965 when, at the end of her working life on the Dart, she was purchased by the Paddle Steamer Preservation Society. She had a short spell working out of Cowes on the Isle of Wight before the Society moved her to Chatham in Kent and spent 15 years restoring her. Starting in 1985, she offered trips on the river Medway and met up with Waverley on a number of occasions.

In December 2012, after an absence of 47 years, she returned to her home waters on the River Dart, to be operated by the Dartmouth Steam Railway and River Boat Company. It was felt that she had a better chance of long-term profitability and survival in the tourist hotspot of Dartmouth with all its naval and engineering history.

Our 90-minute excursion on Kingswear Castle was a wonderful experience which we hope to repeat. I thoroughly recommend that you sail on her if ever you find yourself down in that neck of the woods.

Kingswear Castle has now finished her 2016 season. More information from the Dartmouth Steam Railway and River Boast Company.

Robin Copland is an elected member of CRSC’s management committee.

Swans: Compton Castle, Kingswear Castle and Totnes Castle at Totnes c1955 — copyright CRSC Archive Collection