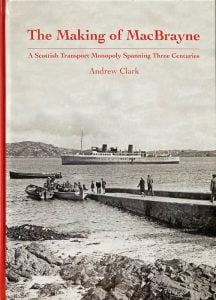

The 504-page book uncovers compelling new evidence on the whole MacBrayne enterprise, reaching back to its origins, detailing its impact on social and economic history, and bringing the story as closely up to date as is possible in our fast-changing times

Iain MacLeod views Andrew Clark’s substantial new book in the context of previous MacBrayne histories, describing it as a ‘definitive labour of love’ which not only sheds fresh light on the past but also offers much to the modern ferry enthusiast.

Followers of Clyde and West Highland steamers and their history have been treated in the last decade or so to a succession of lovingly researched, fulsomely illustrated and beautifully produced books with which to feed their interest: Pleasures of the Firth, Jeanie Deans and From the Clyde to St Kilda spring immediately to mind. Now we are treated to another, perhaps the boldest of them all in ambition and scope: Andrew Clark’s The Making of MacBrayne.

It is nearly 90 years since Christian Duckworth and Graham Langmuir brought out the first book to record in detail the story of David MacBrayne’s steamers. First published in 1935, just three years after CRSC was founded, their pioneering West Highland Steamers was written by two men with very different life stories who had discovered an interest in common.

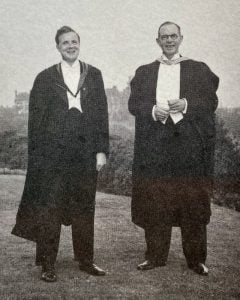

Christian Leslie Dyce Duckworth was born in late 1891, the son of a baronet and distinguished surgeon. After Marlborough College and an engineering degree at Glasgow University, he remained a while in Glasgow, apprenticed to the Fairfield shipbuilding yard. Then, on Christmas Eve 1914, he joined the Scottish Rifles, serving in France and later transferring to the Royal Engineers and eventually the Royal Navy. After the war he worked first for Cunard in his native Liverpool and then, from 1922, for the Burmah Oil Company. The Institution of Mechanical Engineers has several of his specialised publications and notebooks in its archive.

On the face of it, ‘Ducky’ Duckworth — a pipe-smoking, blazer-wearing engineer with an interest in gold and silver hallmarks — had little in common with Graham Easton Langmuir. Eleven years Duckworth’s junior, the man who was CRSC’s honorary secretary for so many years was born in Pollokshields, the only child of a commercial traveller in the wholesale tea trade. Educated at home and then at Glasgow University, he graduated first in Classics and then, in 1933, in Law, the bookish rather than practical discipline which became his profession. In his early twenties he began to have articles published in the Railway Magazine, in January 1932 on ‘Recent Additions to the Clyde Fleet’ and in May 1933 on ‘Sails on Highland Lochs’, demonstrating his eye for completeness and detail by including Lochs Lomond, Eck, Tay, Earn, Etive, Treig, Shiel, Maree and the Caledonian Canal.

One surviving judgement of Christian Duckworth, though, links him directly with the young man who became his Scottish collaborator: he was ‘of an upright and gentlemanly bearing’. Few, if any, CRSC members will remember Christian Duckworth, for he died in 1953, but none who knew Graham Langmuir (who died in 1994) would have any trouble in applying those words to him.

Duckworth (right) and Langmuir, who wrote the first history of west highland steamers 90 years ago, realised they were handicapped by ‘a dearth of data’, of the kind now available to researchers such as Andrew Clark

However it was that their paths first crossed, the two men formed a fruitful partnership and ‘Duckworth and Langmuir’ became a by-word in the literature of coastal passenger shipping. West Highland Steamers paved the way not only for more books of their own, but for a succession of publications by others who to this day follow in their wake. In writing that first book, though, Duckworth and Langmuir were candid in acknowledging one particular stumbling block: “in the case of the older vessels there is a great dearth of reliable data on record for posterity; and we, like others who have trodden a similar path of steamship research, have been severely handicapped in this direction.”

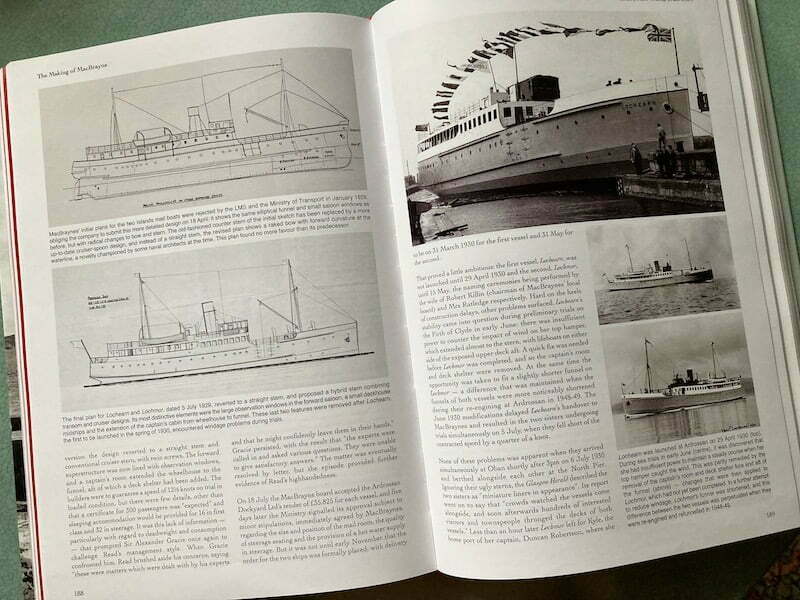

This ‘dearth of data’ can be particularly problematic when the subject of research is a private family concern, for whose record-keeping the men involved were by and large answerable only to themselves: no ‘MacBrayne archive’ has ever been discovered. Despite this, researchers and authors over the years since West Highland Steamers have gradually unearthed information about MacBrayne in all sorts of different ways: Duckworth and Langmuir themselves were particularly assiduous in mining details from company and ship registration records; down the years others have carefully combed newspaper pages, a task now made faster but not necessarily as thorough by digitisation; details of ships’ crews and movements have been gleaned from repositories as far apart as London and Newfoundland; the recollections and anecdotes of passengers and crews have been recorded and passed on for future generations; some shipbuilders’ records have proved helpful; timetables and guide-books often give an added flavour of their times; the internet has been a boon.

Add to all this, of course, the resources of great national archives in Edinburgh and London. These collections contain a wealth of records: but they are records generated not by MacBrayne but by agencies (largely governmental) with which the firm had dealings, agreements, contracts, disputes. Searching for what is relevant amongst them can be a time-consuming and sometimes frustrating challenge, hope sometimes kindled by a brief catalogue description only to be dashed when the document arrives and is, perhaps, a single sheet of bland officialese.

Andrew Clark has made it his business assiduously to search out evidence and uncover new detail about ‘the making of MacBrayne’ in all these ways and more, as the list of sources towards the end of his book makes clear. Those sources include the Postal Museum in London, and here I should declare an interest. Some time ago, I realised that the archives of the General Post Office, catalogued online, seemed to include a variety of possibly interesting documents relating to Scottish steamer services. I had not acted on this discovery until I realised that it might be of interest to the author of what was at the time intended to be a book about the development of David MacBrayne from the 1930s onwards. So, Andrew and I went together to get a flavour of what was there.

The Making of MacBrayne devotes a whole chapter to the Western Ferries saga, when MacBraynes were outgunned by a commercial upstart at Islay

Researchers thrive on the delivery of documents, their unwrapping and unfolding and the search within them for information, a search sometimes made more difficult by near-illegible script. It is an experience all the more exciting when it becomes apparent that the documents have remained unwrapped, unfolded and unread for decade upon decade and that they offer a whole new level of detail about the topic of research. At the Post Office, as well as documents relevant to the original scope of his book, Andrew discovered hundreds of pages of spidery Victorian handwriting shedding new light, in extraordinary detail, on the way in which the business of David MacBrayne evolved in tandem with the developing needs of the GPO.

It was an opportunity and a challenge too tempting to resist, an archive impossible to ignore. The project became, in prospect, what we now have before us — a history of the whole MacBrayne enterprise reaching back to its origins, tracing the ever-shifting nature of the subsidies so essential to its viability and bringing the story as closely up to date as is possible in the fast-changing times in which today’s conglomerate operates, almost unrecognisable but still bearing the name MacBrayne.

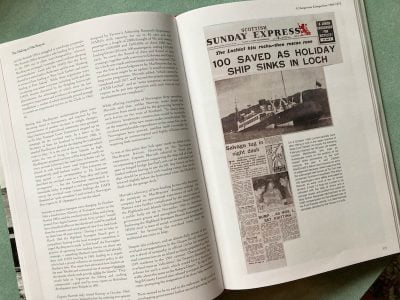

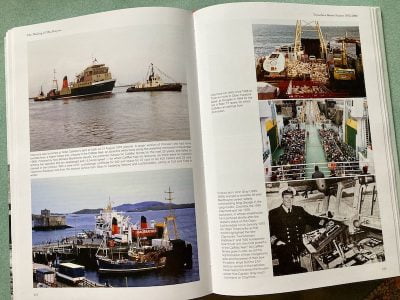

This latest MacBrayne book is emphatically not a dry-as-dust business history. It is a compelling tale, expertly told and beautifully illustrated, presented to us in a handsome and substantial volume which will appeal as much to the modern ferry enthusiast as it will to those who hanker after the old days. As well as exploring commercial and political decisions and ramifications it is the story of a family business with all its possibilities and tensions, key figures firmly at its heart and buffeted all the while by war and peace, by economic boom and bust, by public opinion, by highland storms and rocks. It tells of the crucial part which the company has played for almost two centuries in the social and economic history of Scotland’s western seaboard. It chronicles the development of a fleet always remarkable for its variety. It records the changing ways in which that fleet has been deployed, the characters who have worked aboard, the inevitable catalogue of misfortunes, the high days when a new ship or indeed a new route brightened the life and the prospects of a community.

It is a book exceptionally rich in carefully chosen illustrations of steamers, ferries, people and scenery. Unless the ‘MacBrayne archive’ does one day turn up in the dusty strong room of a Glasgow solicitor (if such places still exist), it is difficult to imagine that in its 500 pages The Making of MacBrayne leaves unexplored many significant avenues of enquiry and discovery.

‘Exceptionally rich in carefully chosen illustrations’: the new book incorporates the 50-year development of CalMac, and features a double-page spread of photos of the 1978 Claymore

Graham Langmuir was a generous man, ever eager to encourage those who sought to follow his example in uncovering the history of the ships which meant so much to him, happy to acknowledge that there was always more to be found out. The Making of MacBrayne would surely have delighted him, adding as it does such compelling detail and so comprehensively bringing up to date the story he was amongst the first to tell, those 90 years ago. He would have been glad to see such happy use made of the collection in Glasgow’s Mitchell Library which bears his name. He would have joined the rest of us in offering congratulations and thanks for Andrew Clark’s definitive labour of love and in relishing the twists and turns of a story told afresh, a story so painstakingly, authoritatively and vividly brought to life in words and in pictures.

The Making of MacBrayne – A Scottish Transport Monopoly Spanning Three Centuries by Andrew Clark; published by Stenlake Publishing Ltd, 2022; 504 pages, illustrated throughout (b&w and colour), £75. Available post-free from the publisher or from Amazon and reputable booksellers.

Iain MacLeod was CRSC President in 1988-89 and 2008-09, and editor of Clyde Steamers from 1993 to 2007.

A tale of the ‘inevitable catalogue of misfortunes, as well as high days when a new ship or indeed a new route brightened the life and prospects of a community’

Published on 7 September 2022