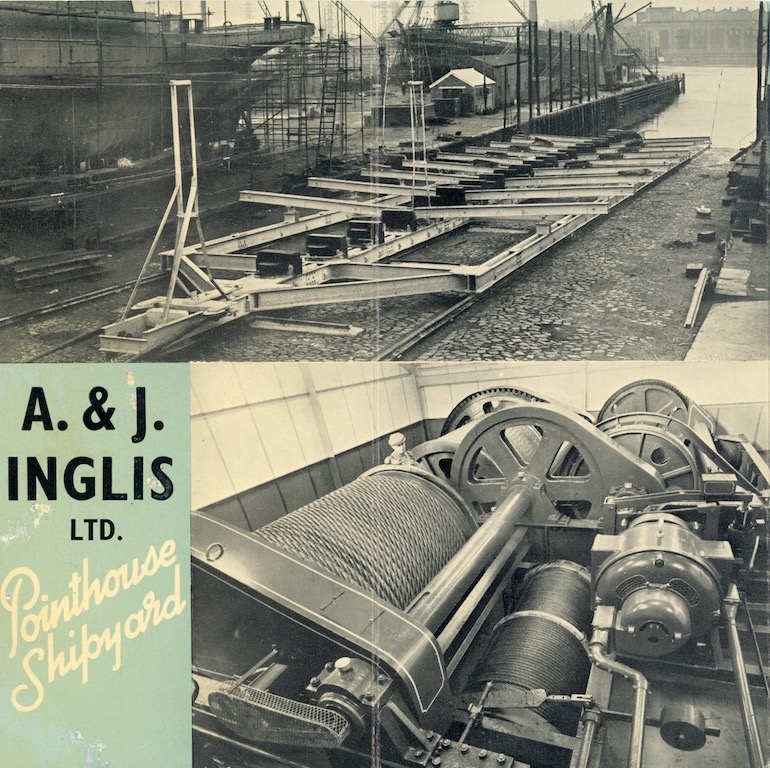

Inglis produced a brochure in 1953 to advertise the yard’s new slipway carriage and winding gear. On the left of the main photograph you can see a vessel being built on one of two ‘top berths’ that necessitated a side-slipping operation before launch on the slipway. This vessel was one of four ‘Confiance’ class ocean-going tugs that were designed by Ian Ramsay for the Admiralty. Ian elaborates on these points in his article below

In the 1940s CRSC member Ian Ramsay served an apprenticeship with A. & J. Inglis of Pointhouse, builder of Waverley. Before the yard closed in 1963 he was its General Manager. Here he recalls some of its idiosyncrasies — notably the mud impeding the slipway carriage in the River Kelvin, and the building and repairing of ships on two ‘top berths’, from which hulls had to be manoeuvred sideways across dry land prior to launch.

Over the years many photographs have appeared in both the press and the CRSC magazine of ships being built at the ‘top berths’ of A. & J. Inglis’ Pointhouse shipyard. Some of the photographs have been taken in the shipyard — Talisman and Maid of the Loch come to mind — but many were taken from an open carriage window on a passing train, giving an excellent picture if one was quick enough with the camera.

The Pointhouse shipyard had three conventional building berths which allowed end-on, dynamic launching into the confluence of the Rivers Clyde and Kelvin. In addition there were two ‘top berths’ that were isolated from the River Kelvin. They consisted of a level area of ground on the east side of the patent slipway, with a surface height that was about level with the top of the keel blocks at the landward end of the slipway carriage. This was more regularly used for hauling ships out of the water for underwater repair and maintenance.

Photographs in an Inglis trade brochure (above) show the new slipway carriage and winding gear that, in 1953, replaced the original 1867 water hydraulic, hauling mechanism and wrought iron and timber slipway carriage. This new facility was similar to the 1902 slipway carriage at Balloch and its successor. The water hydraulic mechanism consisted of a large cylinder and ram with a seven-foot stroke, to which a series of seven-foot-long wrought iron links, each with a diameter of four inches and weighing about 300lbs, were progressively either connected or disconnected.

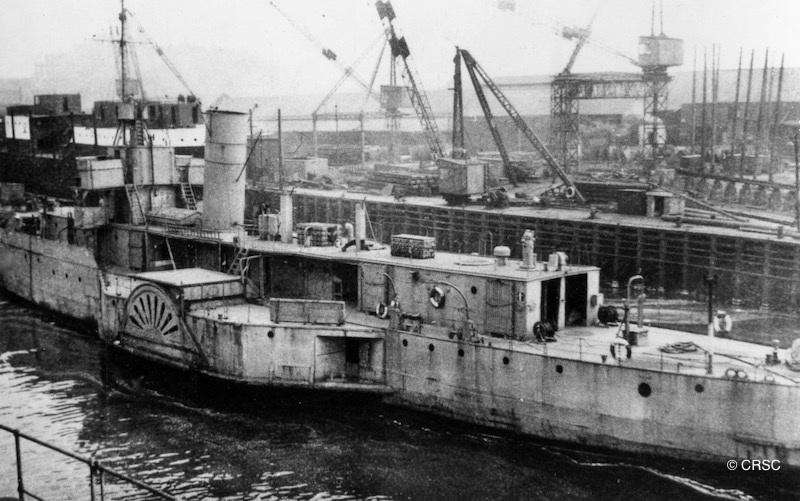

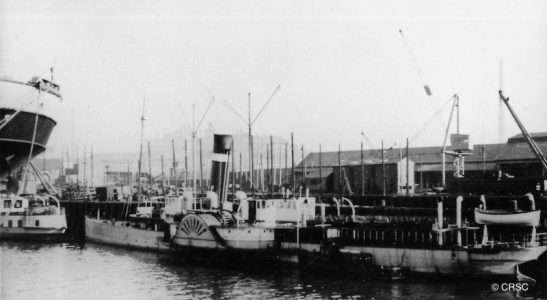

The Pointhouse yard in the early spring of 1947: Waverley is at the fitting out quay and Talisman is being overhauled on the slipway

The process was simple but time-consuming, as the carriage had to be lowered down the length of the slipway to gain a sufficient depth of water at high tide to accept the draught of the intended vessel for slipping. The method was that the ram pushed the carriage down by its stroke (seven feet). At the end of the stroke, the wrought iron link was then disconnected from the ram, and the ram was returned to the withdrawn position and another link inserted. This process was repeated until the carriage was in the desired underwater position.

Once the intended ship had been correctly located above the carriage and the bow had landed, or ‘sued’, on the centre line keel blocks, the process was repeated in reverse, with the wrought iron links being progressively removed until the carriage and ship were finally clear of the water at high tide.

The wrought iron links were quite heavy, and had to be lifted by a small hand-operated crane outside the winch house, which was so positioned that it could access both the ram and the pile of not-in-use links at the head of the slipway.

Apart from age and labour intensity, one of the main reasons for replacing the hydraulic ram hauling mechanism in 1953 was that the links were not sufficiently robust in compression to push the ploughs at the riverside end of the carriage through the mud with which the River Kelvin always abounded. Because of this, the new electric hauling winch was fitted with a rope downhaul that could pull the carriage through the mud to gain the desired amount of water above the keel blocks on the intended tide.

The Humber paddler Lincoln Castle is pictured being fitted out at Inglis in 1940. A larger vessel (background, left) is lying on one of the top berths: Ian says this ship is either an Admiralty trawler or HMS Coreopsis, a ‘Flower’ class corvette which was used as HMS Compass Rose in the post-war film The Cruel Sea

When Pointhouse closed in 1962, the only suitable dredging plant owned by the Clyde Navigation Trust that could have cleared the mud at the end of the slipway was a small single-grab hopper-dredger, Sir William H Raeburn (the longest name in their fleet), but indiscriminate use of its grab was likely to damage the rails, so it was not allowed near the slipway. The answer would have been a small suction dredger, but the Clyde Trust did not possess such a newfangled piece of equipment, nor did they use one until they had disposed of their own dredging fleet and put their maintenance dredging in the hands of contractors.

It was left to the shipyard, using the dockside crane with a grab and buckets, to try to remove as much mud as possible by that method.

Turning now to the ‘top berths’, they were a unique Pointhouse feature, situated beyond the head of the three river building berths and capable of taking two ships, side by side, with each up to 300 feet or so in overall length. These berths were roughly in line with the junction of the former Pointhouse and Ferry Roads. In the early days they accommodated even longer ships: the old Inglis photograph albums had images of one of the earliest oil tank steamers, Bayonne of 1889, and a British India Liner, Dunera of 1891, under construction on these berths. The former was 330 feet long, the latter 425 feet.

The LNER diesel-electric paddler Talisman was built on one of these top berths in 1934-35. So were Maid of the Loch in 1951-52 and other ‘piece small’ ships for assembling overseas – such as those for the Irrawaddy Flotilla Company of Burma.

The photograph of Talisman on the slipway (above left) clearly shows that her maximum designed overall beam was dictated by the width between the slipway retaining walls. The photograph of the new carriage shows one of the 140-ft long ‘Confiance’ class Admiralty oceangoing tugs, building on a ‘top berth’ with her sister out of sight alongside on her starboard side.

The photograph of the Humber paddler Lincoln Castle (above right) shows her ready for handover to the LNER, complete with North British lum, but in the distance can be seen the stern part of a deep-draught ship, either an Admiralty trawler or more likely HMS Coreopsis, a ‘Flower’ class corvette being prepared for launch; more of this later. It was HMS Coreopsis that doubled for HMS Compass Rose in the film version of The Cruel Sea.

The following somewhat unconnected anecdote was told to me by Charlie McLean, Chief Engineer on Jeanie Deans and later Queen Mary II. It concerns Lincoln Castle when she left for the Humber. The ship had been painted grey and had some armour fitted around the wheelhouse, but the compass had not been readjusted to take account of this metal close to the binnacle. The upshot was that, after several days’ steaming in heavy weather after rounding the Mull of Kintyre, the foredeck was damaged and set down, and the crew had no idea of their true position.

They eventually got this from a passing Admiralty trawler and, with the knowledge that they were near Barra Head, it was a case of ‘about turn’ and back to Pointhouse for repair. I am not sure whether this delivery voyage, with Charlie as Chief, was before or after his final trip as Chief Engineer of the 1899 Waverley to Dunkirk, but I think it was before.

Kenilworth at Pointhouse in 1938, waiting to be scrapped in the yard where she had been built 40 years earlier

Ships were built on the ‘top berths’ in the same manner as those on a riverside berth, except that they were usually built on a level base rather than on a declivity or slope.

They were supported on keel and bilge blocks during construction, with bulkheads and topsides liberally supported by timber shores just as on a more conventional building berth. At a certain point in the construction cycle, the shipyard was faced with getting this newly built vessel from its dry land building site into its natural element, and the method of achieving this was known as ‘side slipping’.

Depending on the ship’s length, six or eight transverse launch-ways were laid under the ship and up to the edge of the patent slipway. On top of these liberally greased standing ways, each with a small declivity towards the patent slipway, were placed sliding ways, each with a closely fitting timber cradle that would support its part of the hull during the short journey.

The foremost and aftermost standing ways were marked off in white at one-foot intervals, so that the foreman carpenter and his ‘under gaffer’, by means of white hankie signals, could ensure that the ship’s movement remained parallel! No VHF radios in those primitive days.

Having built the ship and blocked it up on launch-ways, how was it moved? The picture of Lincoln Castle shows that other kenspeckle feature of Pointhouse — the sheer legs, built by the company and so positioned that they were in line with the centre of the ‘top berths’.

The steam engine that was used for hoisting and lowering machinery into ships being fitted out could be alternatively connected to winches that were used for hauling the ship across and on to the slipway carriage. This was achieved by means of huge multi-sheave blocks in association with multi-part wire ropes.

When the centre line of the ship was aligned with the centre of the carriage, the transverse sliding and standing launch-ways had to be removed along with the supporting timber cradles while, at the same time, keel blocks and bilge blocks had to be progressively fitted between the ship and the carriage.

The original 1867 carriage had been fitted with a line of water hydraulic jacks along its centre to assist with levelling the ship down on to the carriage. I never saw them used and they were not repeated on the new carriage.

I remember witnessing, one August evening in 1951, the launch from the old carriage of a large whale catcher, Anders Arvesen, that had been built on a ‘top berth’. After several unsuccessful attempts to push the carriage through the River Kelvin mud, it was hauled back up and the security pawls were lifted.

The pin linking the last link to the carriage was then knocked out, and ship and carriage began to run with ever increasing speed towards flotation, accompanied by groans, bangs and sparks. The whale catcher appeared to be teetering on the brink of falling off the carriage at any moment, although not a piece of the supporting make-up was actually displaced. After the catcher was safely afloat the shipyard manager, Jimmy Jeffrey, when passing me, said wryly “Ian, that’s definitely no’ the way to launch a ship!”

Ian Ramsay remembers the launch of the whale catcher Anders Arvesen in August 1951 — it was quite a ‘carry on’. She had been built on one of the ‘top berths’, but the slipway carriage — impeded by mud in the River Kelvin — initially refused to slide her down into the water

Another feature of side slipping applicable to ship repair work was the ability to take a ship needing repair of major bottom damage (or lengthening) sideways off the slipway carriage and ‘park’ it on a ‘top berth’, where it could be worked on whilst still making the carriage available for the repair of another ship.

The G&SW Railway’s turbine steamer Atalanta was one such ship: in May 1913 she suffered extensive bottom damage after losing vacuum at Whiting Bay.

Another was the necessary rebuilding of much of the underwater hull of Eagle III (1910) to a new form after the Buchanan Brothers had rejected her on grounds of insufficient initial stability.

Although the design and construction of the hull had been sub-contracted to Napier & Miller of Old Kilpatrick, the main contractor was A. & J. Inglis who had to ‘carry the financial can’.

Finally, despite the brochure for the new Inglis slipway installation calling it a ‘cradle’, I stick by the term ‘carriage’ — the term always used by us Pointhouse habitués and others from establishments with similar facilities.

See also Ian Ramsay’s article The last vessel to be launched from the Clyde shipyard of A. & J. Inglis.

After the Poi1nthouse yard closed, Ian Ramsay worked for Yarrow & C0, initially as hull estimator and then as shipyard manager, and subsequently as shipbuilding director for Yarrow Shipbuilders and British Shipbuilders. From 1982 until his retirement in 1997 he worked as a marine consultant. He has served as a director of Waverley Excursions Ltd and Waverley Steam Navigation Company Ltd.

Jeanie Deans during her postwar reconstruction at Pointhouse. The photo shows the sheer legs on the right and the railway bridge behind, from which many photographs were taken by enthusiasts on passing trains

Ian Ramsay says that, although this photograph of Duchess of Fife was taken at Lamont’s Port Glasgow slip in 1936, it demonstrates the side-slipping principle better than any of the accompanying photos of the Inglis yard at Pointhouse. Ian continues: “The photo shows a series of transverse standing launchways set up at right angles to the centre of the carriage, with a short length of sliding way under the ship on each. On top of each sliding way there is a timber cradle to support the ship as she is hauled sideways off the slip carriage and on to firm ground. At Inglis, when dealing with new construction, the reverse applied, i.e. from firm ground to carriage.”

This aerial photo of the Pointhouse yard was taken in 1950-51, and shows four whale catchers under construction. One is afloat alongside the fitting out quay, one is building on a conventional launch building berth and two are building side by side on the top berths at the head of the patent slipway. The one nearest the slipway is J K Hansen and the one nearer Ferry Road is Anders Arvesen (see launch photo above). The other small ship fitting out is Nyati, a twin-screw steam tug for East African Railways and Harbours. Her completed twin, Simba, can just be seen lying across the head of Yorkhill Basin

Join CRSC here for £10 and receive all the benefits.

Published on 9 August 2019