Front-page masthead of the Highland News, a journal that gave weekly updates on steamer services to Lewis more than a century ago, painting an historical portrait for today’s researchers

Leafing through old newspaper reports, Colin Tucker opens a window on a forgotten way of life in the Hebrides.

It is very seldom today that we read items about West of Scotland shipping activities in the few local newspapers that have survived. If, however, we turn back the clock, it is possible to find many items on this subject. A century ago a journey by sea was more than a drive-on-drive-off experience. Crossings took longer, ships were smaller, health and safety had not been heard of. All this led to reports appearing in the local press.

Highland News, published in Inverness, had a column almost every week of ‘Stornoway News’, which included many items relating to local shipping services. There seems to have been a number of themes running through these items, and this article takes a look at some of them, dating from the early 1890s until 1915.

Weather

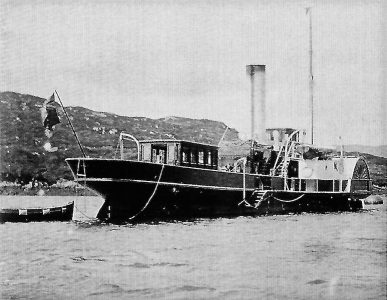

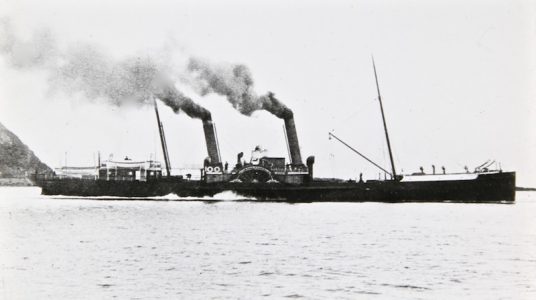

Clydesdale served on many west highland routes for David Hutcheson and later David MacBrayne, but became closely associated with the Stornoway mail run in the 1890s and early 1900s. Built at Clydebank in 1862 with a single funnel, she received two funnels when she was reboilered in 1893. In 1905 she stranded on Lady Rock, south of Lismore. Copyright CRSC

The weather makes only one kind of news today, and that is when it causes ferry cancellations. Not so in the early days. Steamers would venture out in all conditions – the mails had to get through. And this was not always in winter. On 1 July 1893 it was reported that “the weather was very boisterous.” That this was a bit of an understatement can be gauged by the fact that Clydesdale, on the mail run from Strome Ferry, was two hours behind schedule.

Meanwhile, the report continued, “the s.s. Plover, bound [from Stornoway to Lerwick]….put back into harbour. The master stated that, for one hour, while off the Butt, he did not make the ship’s length of headway, notwithstanding that the engines were all the time driving ahead.”

In February 1901, “the prevailing wind was north-east, and this raised a great sea in the Minch….The redoubtable Captain Cameron, of the mail boat, successfully battled with the Minch on Monday and Tuesday, but on Wednesday, on the passage to Stornoway, he was compelled to shelter in Applecross bay. He lay there till half-past five on Thursday morning, and reached Stornoway about one o’clock in the afternoon.”

Only a week later, the mail steamer Clydesdale had more experience of rough weather. On the passage from Kyle “she shipped a heavy sea, something of a tidal wave, which did some damage forward.” As a consequence the ship put into Portree for shelter, continuing her passage to Stornoway at six o’clock the next morning, eventually reaching the Lewis port at about 1pm, a crossing of some seven hours. Highland News added that “the indomitable Captain Cameron and crew are worthy of the highest praise for the manner in which they brave the elements to keep up our regular communication with the outer world.”

Two years later, in February 1903, Clydesdale was again involved in fighting the elements. A gale of south-west wind raged for four consecutive nights. “The force of the wind may be gathered from the fact that on [one] night the mail steamer Clydesdale…. [which] can do the run to Kyle comfortably in six hours, took 14 hours on the passage.”

Only a week later Captain Macdougall on Clydesdale was battling with storms once more. He “gallantly tried out, but the heavy sea running compelled him to put into Portree for shelter. He arrived at Stornoway shortly before noon [the following day], and immediately returned with mails and passengers, returning to Stornoway about about 2.30 [the next] morning, and immediately put about and sailed for Kyle. In this way Captain Macdougall made up the leeway in time without missing a run.”

In May it was fog which caused a delay. “The mail steamer, Glendale, crossing to Kyle….was detained five hours.” The following day, again on the way to Kyle, she ran into a dense bank of fog, and had to drop anchor off South Rona.

At the end of August, the mail steamer was unable to sail until six hours after her usual time “on account of the heavy storm raging.” Only four days later the mail steamer was caught in a gale, but “notwithstanding the difficulties he had to contend with, Captain Macdougall continues to ‘maintain his reputation for good passages, and usually succeeds in delivering his mails on time.”

Another long crossing occurred in December 1904, when the mail steamer experienced terrific weather on the Minch on Monday. “There was a heavy north-easterly gale and the sea was running mountains high, and the passage from Kyle to Stornoway took close on nine hours.”

Built in 1875 at Govan, Glendale plied under various names and on various routes in the English and Irish Channels, the North Sea and the Thames, before being bought by MacBrayne in 1902. Her west highland career was brief: she stranded near the Mull of Kintyre in July 1905. Photo from the CRSC digital archive

It was not only out in the Minch that the weather could cause problems. In October 1907 there was a severe storm which caused damage inside Stornoway Harbour. As a Hull steam trawler was shifting position, she fouled the anchor gear of another trawler. With the wire cables of the latter vessel’s two anchors wrapped round the propeller of the first, she “drifted helplessly on to King Edward’s Wharf, where she collided violently with the stern of Messrs Macbrayne’s steamer Clansman.”

Accidents and deaths

Today we do not expect either of these things to happen on a ferry crossing, but as will be seen, they were more common in years gone by. In September 1898 the following sad item appeared in the Highland News under the heading ‘Sudden Death’.

“On the arrival of the mail steamer Clydesdale on Saturday night last, the captain reported to the police that one of his passengers – Norman Smith, fisherman – had died on the way across…. he went on board the steamer at Kyle apparently in good health, and lay down to sleep on the top of some fishermen’s bags on the main deck. Some of his companions got suspicious that there was something wrong, and went to rouse him, but found that he was dead. They informed the captain, and at Applecross a doctor was brought on board, but he pronounced life to be extinct.”

Falling overboard was an occasional occurrence, whether it was a passenger or a member of the crew. In November 1903, “while the Stornoway mail steamer Glendale was approaching the pier at Kyle of Lochalsh, the carpenter, Angus M’Aulay, fell overboard and was drowned. A boat was at once launched, and every effort made to rescue the unfortunate man, but he never reappeared.” In June 1907 the third engineer of Sheila was found about 30 yards from the wharf in Stornoway Harbour. A 23-year old native of Glasgow, he had been missing for four days and his body was recovered during ‘dragging operations’.

Falling into the hold of a ship is not a recommended action — a sentiment with which Norman Macleod, lamplighter on board the mail steamer Glendale, might have agreed, had he survived the accident.

On 31 October 1903 it was reported that Macleod “accidentally fell down into the hold, a distance of about 12 feet, and sustained very serious injuries about the head and other parts of the body. The quay labourers were engaged loading a cargo at the time, and in consequence the hatches were removed off the main hatchway, and it seems they were going to move the steamer forward a bit. Macleod, who was ashore, jumped on board, and was crossing to assist with the ropes when he must have tumbled down into the hold, not observing that the hatches were off. No one actually saw the accident happen, but one of the men saw Macleod jump on board and immediately afterwards heard the thud of something dropping into the hold. He gave the alarm and on search being made the unfortunate man was found lying face downwards.”

Less serious was the accident which befell a passenger during “rather a nasty” passage endured by Clansman on her way to Stornoway in August 1900. “When about mid-Minch across, a passenger….had his leg broken by some boxes or barrels falling on him after he himself had been thrown down by the pitching of the steamer in the sea.”

Pier head jumps are a thing of the past — perhaps just as well if accidents like the following one took place. In 1902 Robert Macdonald, a labourer, had a narrow escape with his life at Stornoway Harbour. He was on board Clydesdale, and the gangway having been hauled ashore before he observed it, “he attempted to jump on to the pier as the steamer was moving away. He fell between the vessel and the quay but managed to get hold of the cross ties of the pier, and held till he was picked up by a small boat. He, however, narrowly escaped being crushed by the steamer, which, though engines were at once stopped, had some way on her.”

This section finishes with a sad tale from 1915. “On the arrival of the mail steamer….it was found that Private Kenneth Murray, 2nd Seaforth Highlanders, had died on board during the passage from Kyle….He had been at the front for some time and was coming to Lewis to see his folk on a short leave from France.” At least he died within sight of his homeland, rather than in a mud-filled trench in France.

Welcome Home

The beautifully proportioned Clansman of 1870 was one of the most regular MacBrayne visitors to Stornoway in the late 19th century. She was withdrawn in 1909 and broken up the following year. Photo from a private collection

For years it was the tradition in Stornoway, as on most Hebridean islands, for almost everyone to go down to the pier to welcome home friends and relatives, or just to watch who was coming down the gangway. Today the arrival of the ferry is much more soulless: not only are you unable to get on to the pier alongside the ship, but most travellers drive off the ferry in a continuous string of vehicles, allowing neither greetings nor chat. What follows are a few examples of much more spectacular arrivals.

24 August 1895 – Lady Matheson’s Visit

“On Friday night of last week Lady Matheson [widow of Lewis landowner and benefactor Sir James Matheson] arrived at Stornoway on board the mail boat Clydesdale. As soon as the steamer came in sight beyond the Lighthouse the fact was signalled by the lighting of a bonfire on Goat Island, and a display of fireworks both from the shore and the steamer. By the time the Clydesdale came alongside a very large crowd had gathered on the quay. Provost Smith, Baillie Anderson, Mr Kenneth Smith and Mr Orrock proceeded on board and welcomed her ladyship back to the Lews. Afterwards, when she came ashore and walked to her carriage on the Provost’s arm, she was very heartily cheered, and as she drove away cheers were again raised. We understand her ladyship was very favourably impressed by the hearty welcome accorded her.’

8 January 1898

“Mr Alex Morison and his young bride arrived on board the mail steamer Clydesdale. A large number of friends awaited the arrival of the newly-married couple, and rockets in honour of their home-coming were fired from the ship and the shore.”

14 July 1900 – Our Young Laird

“Major Matheson, proprietor of Lewis, arrived at Stornoway on board the mail steamer. There was a large crowd of townsfolk at the wharf, and Major Matheson received a cordial welcome.”

14 August 1900

“The welcome accorded to Mr A. J. Macarthur, of the Claymore, on his return from his honeymoon trip, accompanied by his bride (Miss Mary Macleod), was of a most enthusiastic kind….The announcement [reached the town] by telegraph that they were en route, and would reach Stornoway by the mail steamer Clydesdale [the] same evening. The arrival of the steamer was greeted by a large crowd of citizens, and a right cordial welcome was extended to the newly-married couple….Mr Macarthur is not only a general favourite among his fellow employees in Mr Macbrayne’s service, where he has been for several years, but with the people of the town generally.”

15 August 1902 – Welcome Home

“Mr David Simpson, steamboat agent, and Mrs Simpson returned from their honeymoon on Thursday night. The steamer was decorated with bunting and flags were flying at the pier. There was also a display of fireworks as the steamer entered the harbour.”

11 October 1902 – Welcoming Colonel Thorneycroft

“Colonel Thorneycroft arrived by the mail steamer on a visit to Mr Platt of Eishken Lodge. When the steamer came round the light, rockets were fired from Mr Platt’s yacht Transit and from the pier-head in honour of the distinguished visitor, and when the Glendale drew alongside the wharf provost Anderson went on board and welcomed him on behalf of the community. As the Colonel came ashore and proceeded along the wharf to the Transit he was loudly cheered.”

13 September 1902

“Major-General Sir Bruce Hamilton KCB arrived at Stornoway on a visit to Major and Mrs Matheson, Lews Castle. As the steamer entered the harbour rockets were fired from the Castle grounds, and as it drew alongside King Edward’s Wharf the provost and Magistrates, as representing the community, went on board and welcomed the gallant and distinguished General to Stornoway and the Lews. There were great crowds of people on the wharf, and enthusiastic cheers were raised for General Hamilton as he made his way to his carriage.”

These clippings from the Highland News tell stories about aspects of shipping in the Hebrides at the end of the 19th century, but they also provide a glimpse of a forgotten way of life. The western isles were more isolated then: people were hungry for news, both local and from further afield. Some of what was important then remains the same as today, such as the mail steamer then and the ferry today coping with the weather, while loss of life was and still is felt strongly.

The community was closer-knit then, and their world was smaller than today’s. The respect and deference paid to ‘lords and masters’ was greater then. Perhaps the biggest difference is the role of newspapers in passing on news — without doubt of greater importance a century ago than in our world of instant communications.

Also by Colin Tucker:

The future of the Outer Hebrides, 40 years ago

Lochs and Lochs, or ‘sailing in home waters’

Crossing the Minch — Variations on a Theme

Colin Tucker’s widely admired book Steamers to Stornoway is available in the CRSC Shop.

Join CRSC now for £10 and receive all the benefits — discounted prices, exclusive magazines, special events, meetings, cruises.

Published on 11 August 2018