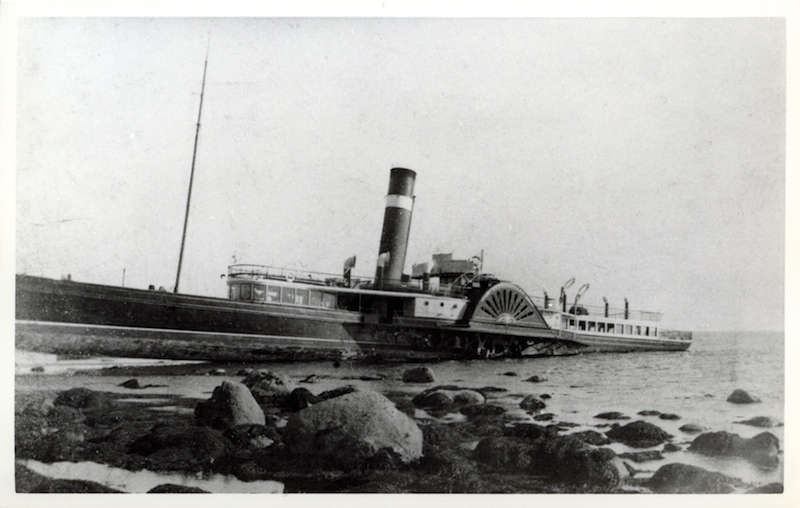

Sliddery slope: Redgauntlet on the morning after she ran aground in August 1899 — copyright CRSC Archive Collection

When Redgauntlet ran aground during a cruise round Arran in August 1899, it took two hours to get her passengers ashore and another 24 to get everyone on their way home. Iain MacLeod sets the scene for the biggest drama of the 1899 season and, beneath the Board of Trade’s full report, fills in details of the incident and its aftermath.

1899 was quite a year for Clyde steamers. The highlight was surely the launch of the North British flier Waverley at the end of May and her trials just over five weeks later, when apparently she reached the remarkable speed of 19.73 knots.

There was plenty of less welcome drama, though. Steamers broke down: Edinburgh Castle had paddle wheel trouble at Cove in late August and Marquis of Bute took her passengers on to Lochgoilhead; not long afterwards Jupiter was also crippled by a wheel failure some miles out of Ardrossan and had to transfer passengers to Duchess of Hamilton; when Marchioness of Bute’s throttle spindle failed off Wemyss Bay one September day her passengers were delayed for three hours.

The weather could be awkward. One stormy January morning, having boarded just three passengers at Millport, Caledonia met a huge sea between the Eileans and the Spoig, which swept her stern and flooded the saloon. On another rough day, in mid August, Captain McTavish of Neptune decided to head for Ayr instead of Stranraer: the passengers protested, so the Master changed his mind – and everyone on board had a rather uncomfortable trip.

There were collisions – and not just the one in June between Marchioness of Lorne and Glen Sannox. Davaar ran into the tug Monarch in mid January, with loss of life on the tug; her fleet-mate Kinloch collided twice, losing her figurehead in March trying to overtake a bigger ship in the river and at the very end of July running into a dredger in dense fog.

There were unusual sailings: on 1 September Marchioness of Lorne was chartered to take the Duke and Duchess of Argyll from Campbeltown to Inveraray; on 13 November Minerva took the Marquis of Bute from Kilchattan Bay to Ayr and recuperation at Dumfries House.

There were near misses – a passenger from Ivanhoe went into the water during a June charter call at Campbeltown – and there were fatalities, like the drowning of a deckhand on Duchess of Hamilton who fell into the water one night at the end of May and the death in June of a man helping to coal Davaar at Gourock. Falling between steamer and pier, he fractured his skull.

Steamers sometimes ran aground but usually got off quickly and undamaged: in mid March Minerva went ashore near Craigmore and in July Davaar fell foul of a very low tide near Dunoon.

None of these, though, attracted anything like the nationwide attention given to the events of 16 August 1899. An official investigation looked into what happened that day:

REDGAUNTLET (S.S.).

The Merchant Shipping Act, 1894.

In the matter of a formal investigation held at the Debts Recovery Court, County Buildings, Glasgow, on the 11th and 12th days of September, 1899, before Thomas Alexander Fyfe, Esquire, Sheriff Substitute of Lanarkshire, assisted by Captains George Richardson and Alexander Wood, into the circumstances attending the stranding of the British steamship Redgauntlet, of Glasgow, on or near the Iron Rock Ledges, south-west coast of Arran, on 16th August, 1899.

Report of Court.

The Court having carefully inquired into the circumstances attending the above-mentioned shipping casualty, finds for the reasons stated in the Annex hereto, that the cause of the casualty was the failure of the master to acquaint himself with the information contained in the Sailing Directions applicable to the locality, and his allowing the vessel to be steered too close along the shore. The Court finds the master, Archibald McPhail, liable in twenty pounds towards the costs of the inquiry.

Dated this twelfth day of September, 1899.

T. A. FYFE, Judge.

We concur in the above Report.

GEORGE RICHARDSON

Assessors.

A. WOOD

Annex to the Report.

This inquiry was held at Glasgow on the 11th and 12th days of September, 1899.

Mr Alexander McGrigor, Writer, Glasgow, appeared for the Board of Trade, and Mr James Mackenzie, Writer, Glasgow, for the Master.

The Redgauntlet, official number 104,623, is a British steam paddle ship, built of steel by Messrs. Barclay, Curle & Co Limited, at Whiteinch, Glasgow, in 1895, and is of the following dimensions: Length 215 ft., breadth 22.1 ft., depth 7.45 ft. She is propelled by one surface condensing engine of 187 nominal horse power. Her registered tonnage, after deducting 169.63 tons for propelling power and crew space, is 106.93 tons nett. She is fitted with five bulkheads, and is employed as a passenger steamer in the Firth of Clyde. She is registered in Glasgow and owned by Mr Henry Grieson and others, Mr John William Greenfield, of Craigendoran Pier, near Helensburgh, being designated in the transcript of register as the managing owner.

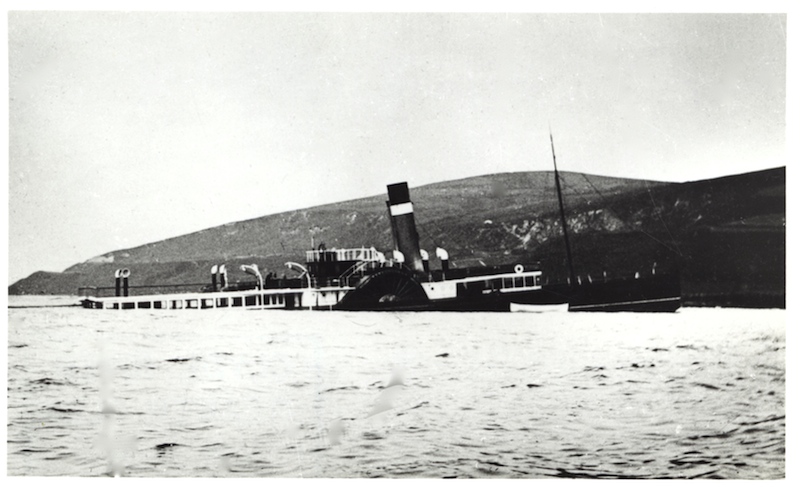

Redgauntlet sets off from Craigendoran, with Lucy Ashton to the right — copyright photo CRSC Archive Collection

On the 16th August, 1899. the Redgauntlet took on board 97 passengers at Millport, and proceeded on a trip round the Island of Arran, under the command of Mr Archibald McPhail, who holds a master’s certificate, No. 103,775, for home trade passenger ships. Her crew consisted of 14 hands all told, and her draft of water was 4 ft. 1 in. fore and aft. She had two lifeboats ready for use, and was otherwise fully equipped with life-saving appliances according to the Statute. The master stated that he had an Admiralty chart of his own with him, but that there was no book of sailing directions on board, nor was the master conversant with the information contained in that book relating to the locality in which he was navigating his vessel. He could have got a book of sailing directions from the manager if he had asked for one, but he did not think it necessary to have one in the kind of vessel he was in — namely a river passenger boat. When the vessel left Millport at 11.50 a.m. the wind was moderate from the westward, but during the day it backed into the south-west, with passing showers of rain. There was one compass on board, a spirit compass placed on the bridge, but it was not used on this trip; the vessel being steered by the land, the man at the wheel using his own discretion in altering the course to suit the trend of the shore. The vessel proceeded at full speed, making about 15 knots, and all went well till Drumadune Point was passed, at an estimated distance of about three-quarters of a mile; no bearing by the compass was taken at any time to ascertain the vessel’s position. After Drumadune Point was passed, owing to the strong wind a choppy sea was encountered from the S.W. The vessel was then steered with Ailsa Craig a little on the port bow. The master stated he considered this course would take his vessel one-eighth of a mile clear of the Iron Rock Ledges, after allowance had been made for leeway. At about 1.55 p.m. Brown Point was passed, at an estimated distance of about one mile. At this time, owing to the choppy condition of the sea, the master instructed the man at the helm not to let her get any closer to the shore. The master stated that, owing to passing showers, the landmarks for clearing the Iron Rock Ledges were not visible. There was some evidence as to the vessel taking a sudden sheer towards the land under the influence of the wind and sea, but the man at the wheel stated that the ship’s head was only thereby altered to the direction in which he proposed to steer, and that this alteration was very little. The master, who was on the bridge, keeping the look-out, did not observe the vessel’s head sheer, or that any alteration whatever had been made on her course. A few minutes after this, when abreast of the Iron Rock Ledges, the vessel was felt to touch something, and almost immediately afterwards water was found coming into the vessel. The pumps were at once started to free the vessel, but the water still continued to rise fast. The master, then, to save the passengers, ran the vessel ashore on the beach at Slidry.

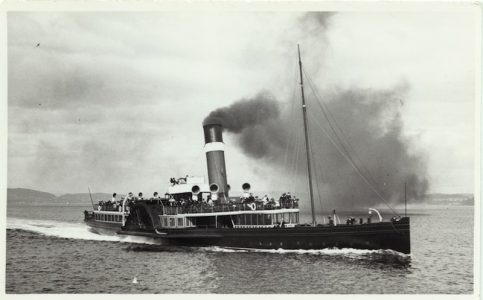

Happier days: Redgauntlet at speed. In 1899 she took on the role of long-distance excursion steamer, with cruises round Arran once a week — copyright photo CRSC Archive Collection

The Redgauntlet was afterwards salved, and taken to Glasgow for repair, when it was found that the bottom of the vessel had received extensive damage, which was said to have been principally due to the action of the sea while lying on the beach at Sliddery.

The following questions were submitted by the Board of Trade, to which the Court gave the answers appended:

1. What number of compasses had the vessel, were they in good order, and sufficient for the safe navigation of the vessel, and when and by whom were they last adjusted? 2. Did the master ascertain the deviation of his compasses by observation from time to time, were the errors correctly ascertained, and the proper corrections to the courses applied? The vessel carried one compass, placed on the bridge. It was in good order, and sufficient for the safe navigation of the vessel. The deviation was correctly ascertained and the compass was adjusted in July last, but on the trip in question the compass was not used.

3. Was the vessel supplied with proper and sufficient charts and sailing directions? The master supplied himself with an Admiralty Chart, but the Book of Sailing Directions applicable to the locality was not on board, nor had the master made himself acquainted with its contents. It has been suggested in this inquiry that these Sailing Directions are intended only for deep sea vessels, and not for pleasure steamers of light draught plying in waters such as the Firth of Clyde. The Court cannot for a moment countenance the view that the usefulness of the official Sailing Directions is to be judged of by the size, class, or trade of a vessel, and, besides, in this particular instance, the Redgauntlet, although a river steamer with a very light draught, was making a sea voyage. If it is the case, as stated in this inquiry, that a knowledge of the Sailing Directions is not regarded as a necessary qualification for masters of river passenger steamers, the Court is emphatically of opinion that steps should be immediately taken to correct this erroneous view. The present case illustrates that a knowledge of the Sailing Directions is often the only way in which dangers of navigation can be avoided.

Steering clear: a decade after her encounter with the rocks off south-west Arran, Redgauntlet was sold to the Forth, where she often gave cruises to the Bass Rock — copyright photo CRSC Archive Collection

4. Were proper measures taken to ascertain and verify the position of the vessel when she was off Drumadune Point on the afternoon of the 16th August, and from time to time thereafter? No measures were taken to ascertain and verify the exact position of the vessel off Drumadune Point or subsequently.

5. Whether, having regard to the state of the wind and sea, and to the light condition of the ship, safe and proper courses were set and steered after passing Drumadune Point, and was due and proper allowance made for tide, currents, and leeway? No courses were set, the vessel being simply steered along the shore at an estimated distance off.

6. Was a good and proper look-out kept? The only look-out kept, and all that was in the circumstances necessary, was that by the master himself from the bridge.

7. What was the cause of the casualty? The cause of the casualty was that the vessel was navigated too close to the land.

8. Was the vessel navigated with proper and seaman like care? The vessel was not navigated with proper and seamanlike care.

9. Was the serious damage to the s.s. Redgauntlet caused by the wrongful act or default of the master and mate, or of either of them? The master was in default in respect: (1) That not having himself sufficient local knowledge he failed to acquaint himself with the information contained on page 110 of the Sailing Directions; (2) that he failed to follow the directions given on the chart; (3) that he left the directing of the vessel’s course round the land to the discretion of the man at the wheel, and failed to observe that he was taking her too close inshore. The mate is not in default. The Court cannot, in the circumstances, absolve the master from responsibility for not sufficiently informing himself of the dangers of navigation, but prompt and proper action to remedy a mistake is only second in importance to avoiding making it, more especially when the safety of a large number of people is at stake, and the Court was very strongly impressed with the promptitude of the master’s recognition of his mistake, and the effective measures which he took to secure the safety of the lives on board, and having regard to this, and to his personal high character, it has, although with considerable hesitation, concluded to refrain from suspending his certificate, but finds him liable in twenty pounds sterling towards the cost of the inquiry.

The Court is of opinion that in a much used-channel like Kilbrennan Sound so serious a danger as these Iron Rock Ledges ought not to remain unmarked.

T. A. Fyfe, Judge.

We concur.

George Richardson,

Assessors.

A. Wood.

(Issued in London by the Board of Trade on the 6th day of October, 1899.)

Earlier in the season, Redgauntlet had taken the afternoon cruise Round Bute, but when this became Waverley’s she started a new programme of long distance excursions. One of these was the weekly trip Round Arran which went so badly wrong on August 16.

Leaving Craigendoran around 9.00 and calling at Kilcreggan, Kirn, Dunoon, Innellan, Rothesay and Largs, Redgauntlet then went to Millport and landed a party of about 250 from the Dumbarton Co-operative Society. At about 11.50 with some 135 aboard she set off round Arran by way of Garroch Head, the Cock of Arran and Kilbrannan Sound. She was not the only excursion steamer to pass the island’s western shore that blustery day: Glen Sannox had a special trip from Ayr to Lochgoilhead.

Archibald McPhail had taken command of Redgauntlet when Malcolm Gillies was given charge of Waverley: this was his third trip Round Arran that summer. He had in the past done the voyage by chart, taking bearings, but Redgauntlet was steered only by landmarks. Nearing the southern end of the island McPhail’s only instructions on the bridge were not to go close to the land.

Most were at dinner when, some time after two o’clock and doing 14 or 15 knots, Redgauntlet struck the Iron Rock Ledges. Some passengers fell off their seats and there was such an inrush of water that the dining saloon floor was forced up. Two men acted immediately: the Chief Engineer, suspecting a paddle float problem, reduced speed; the Second Steward rushed to tell McPhail what had actually happened. The Master quickly instructed the Chief to put the engine Full Ahead again: but after the steward returned to emphasise the danger McPhail decided to run Redgauntlet ashore.

A rocky shoreline made it difficult for the ship’s two lifeboats to get close, so even with the help of around 30 farm workers it took about two hours to get everyone ashore. Local residents pulled the boats as close in as they could and then carried people ashore, arranging for those who wanted it to be looked after nearby.

A telegram went off, explaining what had happened, and two rescue missions were mounted. The first was straightforward: Lucy Ashton went to Millport to collect the Dumbarton Co-op party. Waverley also sailed out, between five and six o’clock, with the intention of finding Redgauntlet. Details were so sparse, though, that she started looking in the wrong place, at the northern end of the Kilbrannan Sound. Sailing south, she sent up rockets until one soared up in reply. By one account Waverley then sent a boat ashore, only to discover there was nothing to do. Redgauntlet’s crew may not all have realised they had been found, for at half past one in the morning the Craigendoran stationmaster received from Whiting Bay a telegram from the Chief: ‘Passengers all safe; not seen steamer; arranging to bring them on by brake to Whiting Bay in the morning. Steamer sunk.’

Waverley had reached Whiting Bay at about three in the morning to find just a dozen passengers waiting. Given ‘a good tea’ on board Juno, at about four o’clock they set off on Waverley for Craigmore (to land two American teenage boys) and Craigendoran, arriving around seven.

About then Lucy Ashton left to collect the bulk of the passengers from Whiting Bay, expecting to leave with them at about eleven. Because of the terrain and a shortage of transport, though, there was some delay in assembling them all and she did not leave until three in the afternoon.

The following Sunday afternoon Lucy Ashton returned to Arran, to collect members of Redgauntlet’s crew who had stayed aboard and to let officials see their damaged steamer. The party included the Superintendent Engineer, the NB Steam Packet Company Manager and Dr John Inglis, shipbuilder and NB director. Redgauntlet’s back was not broken after all and the damage was slighter than feared: the Glasgow Salvage Company planned to refloat her on the week’s spring tides and Thursday saw the job done. Next morning Redgauntlet was towed to Inglis’ Pointhouse slip.

On September 9 an advertisement in the Glasgow Herald asked passengers on board that Wednesday afternoon to contact Captain McPhail’s lawyers – a sign, perhaps, that a serious penalty was a real possibility. As it turned out, and despite some pointed remarks, McPhail kept his certificate. He had sailed with William Robertson’s ‘Gem’ line before joining the NB – and he later returned to them, dying on the shores of his native Loch Fyne in October 1940, aged 77.

The morning after the night before: view from the shore of Redgauntlet at Sliddery — copyright CRSC Archive Collection

Heyday: this study of Rothesay pier during its 1899 reconstruction finds Redgauntlet in the foreground, with Columba, Lord of the Isles and a Caley steamer berthed along the face of the pier — copyright photo CRSC Archive Collection