Record-breaking era: Duchess of Montrose, Marmion, Queen Alexandra and Duchess of Argyll compete for pole position as they head across the Firth for Dunoon in the summer of 1930

During CRSC’s first year of existence, its 16-year old founder, John Wood, gave a talk on a subject he knew from first-hand experience: how many different steamers you could board in a single day on the Firth of Clyde. He had set a new record in the summer of 1932, and was clearly proud of it.

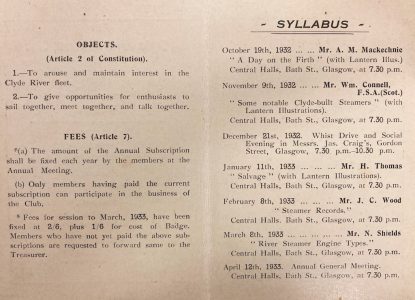

His talk was given on 8 February 1933 at the Central Halls, Bath Street, Glasgow.

The handwritten manuscript was recently uncovered in the Stromier-Vogt Collection, and we are delighted to publish it as part of CRSC’s 90th anniversary celebrations. The talk shows that John Wood was more than a bundle of schoolboyish enthusiasm; he was a determined, articulate and witty young man.

Despite the occasionally breathless flavour, he displays an intimate knowledge of the manifold complexities of steamer timetabling at a time when there was a choice of 18 railway steamers in operation on the Clyde — a world that, from today’s perspective, must count as steamer-hopping heaven. In that light, his account gives us fascinating insights into a bygone age of travel on the Firth.

The scope of his record-breaking day deliberately excluded the Williamson-Buchanan and MacBrayne fleets: Columba, King Edward, Queen Alexandra, King George V and the ‘doon the watter’ paddlers do not even enter into his thinking.

The scope of his record-breaking day deliberately excluded the Williamson-Buchanan and MacBrayne fleets: Columba, King Edward, Queen Alexandra, King George V and the ‘doon the watter’ paddlers do not even enter into his thinking.

John’s manuscript does not give a date for his epic adventure on the Firth, other than that it took place on the day of Rothesay Illuminations, but an article he wrote for Clyde Steamers in 1971, two years before his death, states that it was Friday 26 August 1932. That article, which we publish separately in digitised format as a ‘Members Only’ post, sets his ‘Blue Riband’ day in the context of other record-breaking attempts before and after his own, with carefully tabulated details. As with his teenage musings below, it makes for a compelling read.

Back in 1932, spurred by his steamer-hopping exploits, John Wood succeeded in galvanising enough support among fellow steamer enthusiasts, most of them considerably older, to create a Club with a sustainable programme of events.

Although his influence over the Club was limited to its first two or three years (after which his medical career took him away from the west of Scotland), we can count ourselves lucky to have had him as our founder: he was clearly a cheerful soul, and his palpable love of ‘meeting together, sailing together and talking together’ set the tone for all that CRSC has done ever since.

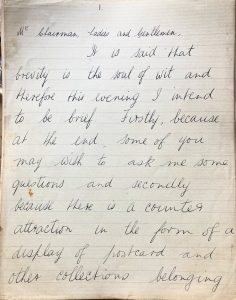

Mr Chairman, Ladies and Gentlemen,

It is said that brevity is the soul of wit, and therefore this evening I intend to be brief. Firstly, because at the end, some of you may wish to ask me some questions, and secondly because there is a counter attraction in the form of a display of postcard and other collections belonging to members.

The Clyde River Steamer Club has, I think, served a very useful purpose since its inception almost a year ago, and those who have attended our meetings regularly will be in complete agreement when I say that not the least important service it has rendered the members has been in throwing a flood of light on so many aspects of steamer interest. I do not pretend that tonight I intend to do anything of the kind.

The subject upon which I have agreed to talk is not one of paramount importance.It may indeed appear to some of you that the business of trying to board a record number of Clyde River Steamers in one day is a feat worthy only of an inmate of Gartnavel or Hawkhead.

Of course, that has been said of many record breaking exploits until it was explained by the record breakers that they were really demonstrating the superior merits of Shell Mex, Castrol or some other propellant.

In the same way, the only reply which I have been able to make to the criticisms of irate relations and friends is that I have been able to demonstrate the superiority of Bovril and Horlicks Malted Milk as sustainers of human energy.

I would not have you believe for a minute, however, that my efforts have been subsidised directly or even indirectly by Messrs Bovril Ltd, or that the L.M.S. or L.N.E. Railway Companies for the sake of accruing publicity have furnished me with free season tickets, or with free lunches or teas in their palatial dining saloons. This despite all efforts by me.

I would, however, suggest that the pastime which I invented is not without its benefits and that it does greatly add to one’s knowledge of steamer speed capacities, to an understanding of the difficulties encountered in framing steamer timetables and to an intimate knowledge of the efficiency or otherwise of the steamer captains and pier masters in their efforts to keep to schedule.

Although the steamer officials displayed a friendly attitude towards my record breaking efforts, the same cannot be said of all the pier masters with whom I came into contact.

The programme of talks for CRSC’s first winter session as set out on the 1932-33 syllabus card. John Wood’s talk was announced for 8 February. Click on image to enlarge

Perhaps they felt that it was rather lowering to the dignity of their pier that it should be used almost as a gangway from one steamer to another.

I recall, indeed, the expression of mingled horror, amazement and disgust with which one of the baggage gentlemen regarded me when I stepped for the fifth time in a matter of five hours on to the pier at Craigmore. His laconic comment was caustic and to the point. “My Goad,” he cried, “what the hell are you doin’ back here again?”

Such incidents, of course, are merely the trials and tribulations, the sorrows, as it were, which are sent to try us, to be borne with stoicism and humility.

It has been of great interest to me to observe the different features connected with the steamers which appeal to different members.

Some, for example, specialise in the History of the Fleet as shown in postcards and newspaper cuttings. Others like to go down to see the engines — I mean the engines that move — while others like to compare the speeds of the various vessels.

My special hobby, which may sound rather unusual, is an interest in steamer timetables, and like most hobbies, sounds distinctly daft to the uninitiated.

And so to my subject: I wish briefly to describe the efforts which I made and which others have made to wrest the ‘Blue Riband of Clyde River Steamer Hustling’ from the very strenuous competition of rivals from such distant ports — such foreign climes — as Greenock and Port Glasgow.

In July 1931, while in search of adventure aboard the steamers, I heard a rumour concerning someone who had managed to board 10 railway steamers in the course of one day.

I was greatly taken with this feat, whether real or imaginary I do not know, and determined to take up the idea, and if possible popularise a record-breaking campaign.

The first thing was to board more than 10 steamers in the course of a day, and right away I began an intensive study of the timetables — working out complicated changes and combinations and incidentally wasting reams of paper in the process.

At this point I think I ought to give you some idea of the system of rules which govern this intriguing sport.

First — The fact that you have boarded 15 steamers does not matter unless each steamer is different. That is essential. The same steamer boarded, maybe three times in the day, only counts as one point.

Secondly — All steamers, in this particular record at any rate, must belong to the railway companies.

And thirdly — The record must be completed within one day by the calendar. The fact that it is done within 24 hours is not enough.

Up to the present, the start and finish of the records has been made at approximately the same port, and although perhaps desirable, this has not been laid down as one of the essential rules.

I was to spend a holiday at Helensburgh, and consequently my start and finish had to be made near there.

Morning scene at Craigendoran c1931, with Waverley (left) and Talisman: ‘Waverley had to coal when she arrived alongside and was fully 10 minutes late in leaving’. Click on image to enlarge

To the inexperienced record-breaker the first and natural impulse is to start the day with the earliest steamer possible, but this is not always the wisest plan, and so after some deliberation I decided that the Lucy Ashton 8.3 from Helensburgh to Craigendoran and not the Jeanie Deans — the 7.36 from Craigendoran — was the best start, and so as 8.15am was clocked on Monday the 3rd August 1931 I found myself standing on Craigendoran pier awaiting the arrival of the Waverley with one steamer to my credit.

The Waverley had to coal when she arrived alongside and was fully 10 minutes late in leaving. This of course made the ‘Argyll’ late. I left the Waverley and boarded the Duchess of Argyll at Dunoon, and she took me as far as Craigmore.

At that pier I landed and it was then that I had my first altercation with the cross-eyed pier master regarding the payment of 2d for merely standing on the pier. I was assured, however, that failing payment I would be there for the rest of the day and possibly the night. Deeming discretion the better part of valour, I paid.

It being a Monday the Jupiter was on the Ayr run and called at Craigmore before Rothesay. I boarded her and went down to Rothesay.

To be quite frank I had no definite plans made for the day, and as the steamers leaving Rothesay at this hour — namely 11 o’clock — are very few, it looked as if I would be stranded for at least an hour.

A bright idea struck me, however, and I walked back to Craigmore where, after enriching the coffers of the pier trust to the extent of another 2d, I boarded the Duchess of Rothesay to return to Rothesay. I then surveyed my morning’s work. Here it is:

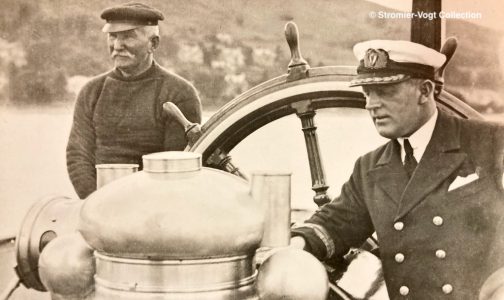

‘Rather timidly I approached Captain Hay [of Marmion] on the subject of letting me off at Craigmore, but after a brief explanation he agreed without hesitation’: Captain Harry Hay (right) is pictured on the bridge of Lucy Ashton in 1930, with pilot Hugh MacKenzie

Waverley – Craigendoran to Dunoon

Duchess of Argyll — Dunoon to Craigmore via Wemyss Bay

Jupiter — Craigmore to Rothesay

and after a walk back to Craigmore

Duchess of Rothesay to Rothesay

Five steamers in 4 hours! Not very like a record!

I thought of getting the next boat home but finally decided to carry on. I got aboard the 12.20 — the Marmion — Craigendoran-bound and decide that another visit to Craigmore would do me no harm. Rather timidly I approached Captain Hay on the subject of letting me off at Craigmore, but after a brief explanation he agreed without hesitation to stop there.

After spending one more hour examining the beauties of Craigmore pier, I got the Duchess of Fife back down to Rothesay. No doubt you are thinking that a little change of scenery from that of Craigmore and Rothesay would do us no harm.

That is just what I thought too, and consequently my next voyage was to Dunoon on board the Duchess of Montrose en route for Loch Long and Loch Goil.

Marmion off Craigmore around the time John Wood established his steamer-hopping record. Click on image to enlarge

A word about the weather — it was on its best behaviour. In fact the day was well-nigh perfect. The peaks of Arran were clearly visible in the south while in the north we could see the Caledonia leaving Kilcreggan. On arrival at Dunoon, my misfortunes began. My next steamer, the L.N.E. from Craigendoran, proved to be no other than the Marmion, which I had already boarded and therefore did not count as an extra steamer. We raced the Mercury to Craigmore and rather luckily beat her, so, once more, I disembarked at that port and boarded her late rival the Mercury to return once more to the ‘Madeira’.

Imagine my disgust and disappointment when I discovered that I had again to board the Marmion — my third time in three hours — to go to Dunoon. The Dunoon to Gourock steamer was of course another double, the Duchess of Rothesay being on this run.

Well! 5.45. Here I was at Gourock with only 9 different steamers and the record still unbroken.

My next journey was on board the Caledonia to Kilcreggan, and there I again boarded the Waverley which of course did not count as I had been aboard her in the morning, and arrived at Craigendoran with the record equalled but not broken. Quickly I produced the programmes and saw that I could get the Talisman to Kilcreggan in time to get the Jeanie Deans back. This I did and so finished my day at 7.45pm.

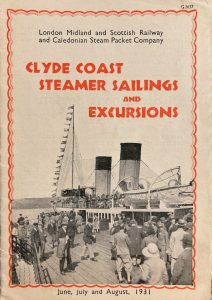

John Wood had to be an assiduous reader of timetables if he was to board as many steamers as possible. The cover of the 1931 LMS/CSP timetable celebrated the advent of Duchess of Montrose the previous summer and set the tone for Caley timetables of the 1930s

Here is a short summary of my afternoon’s work:

Marmion — Rothesay to Craigmore

Duchess of Fife — back to Rothesay

Duchess of Montrose — Rothesay to Dunoon

Marmion — Dunoon to Craigmore

Mercury — Craigmore to Rothesay

Marmion — Rothesay to Dunoon

Duchess of Rothesay — Dunoon to Gourock

Caledonia — Gourock to Kilcreggan

Waverley — Kilcreggan to Craigendoran

Talisman — Craigendoran to Kilcreggan

Jeanie Deans — Kilcreggan to Craigendoran

12 different steamers in 12 hours.

I felt pleased with my feat. I had actually been aboard 16 steamers. My doubles were Marmion (3), Duchess of Rothesay (2) and Waverley (2), which of course only count one point each.

The steamers I had not been aboard in the day were the two Arran boats Atalanta and Glen Sannox, the two Millport steamers Glen Rosa and Marchioness of Breadalbane and the L. N. E. Co’s Kenliworth (spare boat at Craigendoran) — a total of six.

Two days later I returned home and that evening my exploits were recorded in the Evening News.

But my fame was destined to be short-lived. On the following Saturday I was at Rothesay, and just before boarding the Juno for the return journey to Ayr I bought an evening paper. Safely aboard, I opened the News and the first thing that struck me was the following:

“14 Steamers in a Day”

GOUROCK YOUTH THE NEW CHAMPION

I read the report and discovered that James Murdoch of Gourock, now one of the members of the Club, had broken my record by TWO steamers.

Here is the account of his record as it appeared in the News of 8th August 1931:

“A Gourock youth has wrested the ‘Clyde Steamers Championship’ from the Ayr expert within a few days of the latter’s record feat of voyaging on no fewer than 12 different steamers in the course of any one day.

James Murdoch of Tower Drive, Gourock, is the new Champion. On the day when he broke the record he boarded 15 steamers, 14 of these being different. John C. Wood, the Ayr champion, had been aboard 16 steamers but only 12 of these were different.

James’s programme began at Greenock whither he had journeyed by bus. He left on board the Caledonia and arrived at Gourock where he transferred to the Duchess of Montrose.

That steamer took him to Dunoon and there he joined the Duchess of Argyll, arriving at Wemyss Bay to board the Glen Rosa and sail to Largs.

The Marchioness of Breadalbane took him back from Largs to Wemyss Bay, and the Mercury took him from there to Rothesay. On the Marmion he went to Dunoon again, and from Dunoon he went to Innellan on the Waverley, to come back to Dunoon on the Duchess of Fife. The Talisman took him from there to Craigendoran and the Lucy Ashton on to Princes Pier. Back again to Dunoon on board the Duchess of Rothesay and back to Innellan again on the Jeanie Deans. The final voyage from Dunoon back to James’s home town Gourock was made on board the Jupiter.”

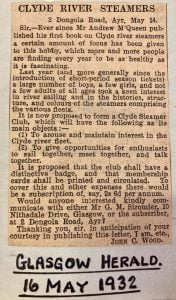

John Wood’s letter to the press in May 1932 set in train the formation of the Clyde River Steamer Club that summer

He had succeeded in boarding 15 steamers, 14 of these being different. The fact that I had actually been aboard one more steamer was poor consolation, and I determined that whatever happened I must regain my lost record.

The following week I spent in a fruitless search of the programmes in an attempt to find some solution to my difficulties. But although I discovered that I could equal his record in a different way, to board more than 14 steamers looked an impossibility, and with winter fast approaching I decided to leave steamer records alone until 1932.

But after all, you say, what good do these records do? Well! They were the indirect cause of the foundation of this club. For it was on these trips in 1931 that I thought of how enjoyable it would have been to have had an enthusiastic companion with me, and so before the 1932 summer began, I wrote the letter to the press advocating the foundation of the club of which you are all members, and it served its purpose admirably, for almost every day during the six weeks which I spent on board the steamers last year did I meet someone wearing the familiar C.R.S.C. pennant. So you see the records were really the foundation of the club, and I think I am safe in saying that even if they render no other service, they will have done their duty admirably.

But let us return to our subject. Ready for the fray in 1932, I obtained the new timetables on the very day they were issued, and began afresh my search for that elusive one steamer necessary to regain the record.

It was going to be a difficult task. Consider there are only 18 railway steamers running on the Clyde in summer. Of these the two Arran steamers Atalanta and Glen Sannox may be ruled out, while it depended entirely upon what particular route the Duchess of Hamilton happened to be, as to whether or not she would be included. This leaves 15 steamers, every one of which had to be boarded in order that the record might be beaten. You will see that the task I had on hand was no easy one, but I was determined that my attempt would be a super one. “Thin” changes would be cut to a minimum — doubles would be used only where absolutely necessary and voyages such as Craigmore to Rothesay or Helensburgh to Craigendoran would be few and far between.

These restrictions were not calculated to make my task any easier but it had got to be done, and for the best part of July, during which I almost lived aboard the Duchess of Hamilton, I veritably swotted the programmes.

I tried all the chief Clyde resorts in turn to find the best starting point: Gourock, Kirk, Dunoon, Innellan and Rothesay as well as Kilcreggan, Helensburgh and even Ardnadam. All had morning programmes arranged for them.

From this emerged the fact that the two best starting points were Rothesay and, strangely enough, Ardnadam. But a holiday at Ardnadam would be rather quiet and so I decided to commence my effort at Rothesay.

I took the Rothesay programme and began to perfect it, and after a few days “touching up” I accomplished my ambition — a record breaking programme of 15 steamers.

Fearful lest any last minute disaster should overtake my effort, I spent the whole of the preceding day enquiring at various piers concerning the routes of some of the L.N.E. steamers which have such a nasty habit of changing over just when one least desires it.

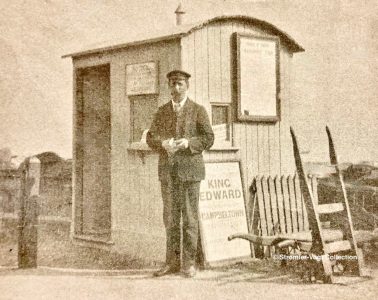

Colin Turner, piermaster at Craigmore in the pre-1914 era. His successor in 1932 gave John Wood a hard time, insisting that he pay pier dues every time he stepped onto the pier during his record-breaking day on the Firth

Like all great challengers the potential champion went to bed early.

At last the great day arrived. Rising in the middle of the night — 5.45 to be exact — the victim ate a hearty breakfast ere setting out at 6.50 aboard the Kenilworth for Dunoon.

There were only two other passengers but as we approached Craigmore I could see another standing on the pier. There appeared to be no one else about and I was horrified to think that here was some wretched individual going with the early boat for the express purpose of avoiding paying his 2d, but I had reckoned without my friend from previous records and ere another minute had passed, he was enriching himself by 2d, to the evident disgust of the “extra passenger” on the pier.

Arriving at Dunoon I could see my connection, Jupiter, lying a good way off the pier. Immediately the L.N.E. boat had left, however, she sailed in and took on her small morning complement.

Prompt to the minute at 7.52 we cast off and at 8.10 I was standing on Gourock pier with almost an hour to wait for the ‘Montrose’.

I took a short stroll through the town, collected a few postcards, and returned to the pier to board the Duchess of Montrose at 9am. Although five minutes late in leaving, we beat the ‘Argyll’ quite easily for the pier and so my next connection was assured. From Dunoon the Duchess of Argyll took me to Wemyss Bay where I caught the Glen Rosa for Largs. I may say in passing that for once she left Wemyss Bay at 9.50, this I think being chiefly due to the fact that the ‘Argyll’ was well up to time. I had had visions of the ‘Rosa’ being too late for me to catch the ‘Breadalbane’ at Largs at 10.45, but my fears were set at rest and at 11.15 I was leaving the ‘Marchioness’ at Wemyss Bay to board Mercury, my seventh steamer, due to leave at 11.30.

John Wood would have had a well-thumbed copy of this 1932 LNER timetable. The front cover was typical of the more functional tone adopted by the North Bank company in the early 1930s

It was 11.23 before the connecting train arrived, and at 11.29 when I thought that all the luggage was aboard and that we were about to cast off, another cart-load arrived. It was 11.34 before we backed away from the pier and it seemed to me as if we would never point our bow towards Rothesay.

At last we did and the race with the Duchess of Rothesay for Craigmore pier had begun. She was just entering Innellan pier as we turned, and being held up there a little longer than usual, we started with a good 200 yards’ advantage. The Mercury is no greyhound, however, and as we entered Rothesay Bay the ‘Duchess’ was only about 20 yards behind. It was going to be a close thing. Eagerly we watched for the signal, as the two boats ran neck and neck for the pier. The inshore vessel was signalled! The Mercury had won!

It was a lucky moment for me. I disembarked and boarded our recent rival, the Duchess of Rothesay, to make the short journey to Rothesay pier aboard her.

Let me give you a summary of my morning’s sailing:

Kenilworth — Rothesay to Dunoon

Jupiter — Dunoon to Gourock

Duchess of Montrose — Gourock to Dunoon

Duchess of Argyll — Dunoon to Wemyss Bay

Glen Rosa — Wemyss Bay to Largs

Marchioness off Breadalbane — Largs to Wemyss Bay

Page 6 of the LNER timetable shows the 4.15pm connection that John Wood needed to catch at Princes Pier for Craigendoran

Mercury to Craigmore and Duchess of Rothesay on to the Madeira completed my morning’s programme. Everything had gone like clockwork, but would my good luck continue? We shall see!

It was just midday, and as my restart was not to be made until 1.20, I had quite a while to wait and was able to return to my holiday home for lunch.

Before my sailing should be resumed, however, I was destined to receive two surprises: one very pleasant and the other the very opposite.

Firstly I discovered that the Glen Sannox was to take a special evening cruise to Rothesay from Largs, and was to leave Rothesay at 8.15 for a short cruise round the bay to view the Illuminations. As I was due to finish my programme at 7.15, the possibility of a 16th steamer seemed well within my grasp. As for the second surprise, just as I was about to board the Duchess of Fife at 1.20, I met Mr Shields, our secretary, and he informed me that the hope of the Caledonia arriving at Greenock at 4.15, being in time to catch the Lucy Ashton leaving for Craigendoran at exactly the same time, was rather remote.

He promised, however, that as he intended to do this sail on the ‘Lucy’ he would endeavour to persuade the Captain to wait for me. It was therefore with feelings of mingled joy and anxiety that I stepped on to the Duchess of Fife at 1.20. This steamer took me to Craigmore and the Marmion brought me back to Rothesay. From there my next vessel, the Talisman, conveyed me on my largest cruise of the day – to Kilcreggan.

‘I went up on to the bridge and asked Captain Robertson if he could possibly catch the ‘Lucy’. He assured me that he would do it quite easily’: Captain James Robertson of Caledonia in 1932

There I awaited the Caledonia with an anxious heart, for if the ‘Lucy’ were missed it was doubtful whether I would even be able to equal the record. Three minutes late the ‘Caley’ left Kilcreggan. It made up these three minutes on the way to Gourock, but left that pier at 4.5 instead of 4 o’clock. I could stand the strain no longer and in desperation I went up on to the bridge and asked Captain Robertson if he could possibly catch the ‘Lucy’. He was exceedingly optimistic and assured me that he would do it quite easily. The ‘Caley’ of course always takes a big sweep into Princes Pier in order to face towards Gourock for the return journey, and when she started on this it looked as if I were doomed. 4.12, 4.13 were clocked. At last we were alongside and as 4.15 struck I dashed along the pier and boarded the ‘Lucy’. I have no hesitation in saying that had it not been for the kind collaboration of the two captains and Mr Shields, my connection would have been missed.

I was now right on the heels of the record with 13 steamers to my credit, and it looked as if a new record were bound to be set up.

But — my troubles were not over. Imagine my surprise when I discovered that the Waverley and Talisman had changed routes and so instead of the Waverley going to Dunoon, Innellan and Rothesay, she was bound for Kilcreggan, Kirn, Hunter’s Quay, Stone, Gourock and Greenock. My course was obvious. I had to get aboard the Waverley, no matter where she was bound for. This I did and landed at Kirn. From there I walked along to Dunoon, and after a brief stay there, a bus conveyed me to Innellan where I was in time to catch the Jeanie Deans back up to Dunoon. The ‘Jeanie’ was just on time and the Kenilworth, my connection for Rothesay, and incidentally my only double, was a little late and so at 7.15 I stepped ashore at Rothesay with 15 different steamers to my credit. A short visit home and a rather belated tea ensued, ere I embarked on the Glen Sannox to view the Illuminations from the bay.

At 9.30 my day finished. I had been aboard 16 different steamers in 16 hours.

Here is my afternoon’s programme:

Rothesay to Craigmore and back — Duchess of Fife and Marmion

Rothesay to Klcreggan — Talisman

Kilcreggan to Princes Pier — Caledonia

Princes Pier to Craigendoran — Lucy Ashton

Craigendoran to Kirn — Waverley

Kirn to Innellan — per ‘bus

Innellan to Dunoon — Jeanie Deans

Dunoon to Rothesay — Kenilworth

Rothesay to the Illuminations — Glen Sannox

My only double was the Kenilworth, and the only two which had eluded me were the Atalanta and my special friend the Duchess of Hamilton.

It had been a great day. To those who think they could go one better, let me say straight away that it is not impossible, although it cannot be done every day. Last year I think there was only one day on which the feat of boarding 18 steamers, i.e. the whole railway fleet, could have been successfully performed.

But if you think that this record is too big a thing to attempt straight away, why not practise with smaller ones until you become an efficient timetable juggler? Why not invent records as I have done? A day aboard royalty and nobility, the Kings Queens Duchesses etc, or what about sailing on the five Duchess ships in succession, a feat which I accomplished while training for the big record. I did it on Monday 15th August from Rothesay by leaving that point on the Duchess of Montrose at 10.5. At Largs I changed to the Duchess of Hamilton and after sailing Round Bute I landed at Rothesay to board the Duchess of Rothesay for Dunoon. The Duchess of Fife brought me back to Rothesay and the Duchess of Argyll on to Wemyss Bay, and thus did I board the five Duchess ships in succession. Incidentally my journey home to Rothesay was aboard the Duchess of Montrose returning from ‘Round the Lochs’, and so the succession was maintained right to the end of the day.

I have told you of one way of spending a summer. I make bold to say it is a good way. It leaves in its wake a silver trail of happy memories. Memories of blue waters, of grey skies, of white winged gulls, of churning paddles and throbbing turbines. It fires in the inner eye, which is the bliss of solitude, memories of that dear old Firth of Clyde, which will continue to bring joy and delight to thousands, and peace and heart’s content to the enthusiasts like ourselves, who ask for nothing better than to spend our summers in this way so long as we have strength enough left to stagger up a gangway.

Transcribed and annotated by Andrew Clark. With thanks to Fiona Stromier.

SEE ALSO:

Eric Schofield: 14 Ships in a Day — A 21st Century Record? (photos)

Eric Schofield: 14 Ships in a Day (text)

16-year old John Wood (centre) with fellow CRSC members George Stromier (left) and Norman Shields (right) on Duchess of Argyll on 24 August 1932, two days before he set a new record for the number of railways steamers boarded on a single day on the Firth

CRSC is still going strong after 90 years. Are you a member of this friendly association of ship enthusiasts? Click here for your £10 introductory membership and you’ll get all the benefits, including the highly prized annual Review of west coast shipping, CRSC’s colour magazine and exclusive access to photo-rich ‘members only’ posts on this website.

Published on 6 February 2023