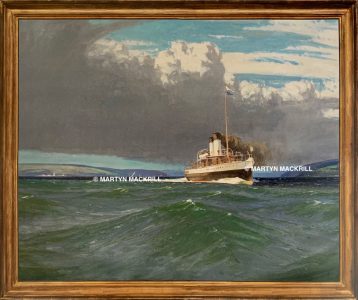

Martyn Mackrill’s painting of King Edward depicts her mid-firth during trials in 1901, with the Skelmorlie shore to the right and Toward Lighthouse on the left. This is the shape of the painting in the format in which you will receive your A3-size print

CRSC is exclusively offering large prints of Martyn Mackrill’s magnificent painting of King Edward, the world’s pioneering turbine passenger ship.

The painting is a radiant seascape depicting the steamer on speed trials on the Skelmorlie mile in 1901, with Toward Lighthouse also visible. It was first published on page six of the 2021 edition of the Club’s magazine Clyde Steamers.

The original painting was bought by a private buyer at a London gallery last month for £28,500.

You can buy your own limited edition print measuring 16″ x 12″ (A3-size), for £20 (£15 for paid up CRSC members).

The prints are ideal for framing and hanging on your wall.

Click here to buy.

If you have not yet joined CRSC, you can do so here for £10, which would automatically give you the £5 members’ discount on the print.

Our supply is limited, so please order without delay. The print will be despatched post-free in a cardboard tube. Allow two weeks for delivery. The copyright watermarks do not appear on the actual print.

These high-quality prints were made from a scan of the original painting. CRSC is extremely grateful to the artist Martyn Mackrill for giving us privileged access to the image. Martyn retains ownership of the copyright.

The prints, which trim the top and bottom of the original image by a very narrow margin in order to fit the chosen print size, have the same pleasing finish as our two previous special print offers — the enlarged colour photo of King George V arriving in Oban Bay in 1971, and the enlarged black-and-white photo of Duchess of Hamilton at Millport. A handful of these are still available at the same price — click here to buy the KGV print and here for Duchess of Hamilton.

Martyn Mackrill (b 1962) in his studio at home in the Isle of Wight, putting the finishing touches to his painting of King Edward on trials in 1901. The son of a Scot, Martyn has kept in touch with his Clydeside roots, returning most years for trips across the Firth and to pursue his interests as a yachtsman. His dramatic paintings of yachts in open waters are much in demand. As for his model of the Glasgow & South Western Railway’s 1898 paddler Juno (left), this was a youthful product of his fascination for Clyde steamers. He counts himself a proud member of CRSC

● ● ● ● ● ●

Martyn Mackrill has developed a reputation as one of the foremost marine artists of our time, writes Andrew Clark.

He is renowned for the imaginative skill with which he captures the play of light on water and cloud, and the authenticity of his portrayals of all manner of craft on the sea — whether they be yachts (his acknowledged speciality) or pleasure steamers such as King Edward.

Born on the Isle of Wight, Martyn has Scotland, steamers and the sea in his blood: his Glaswegian father was a ship’s engineer and his grandfather worked as a draughtsman for Scotts of Greenock and John Brown at Clydebank.

Encouraged by a teacher at school, he began painting ships as a teenager: ‘I always wanted to paint big steamships,’ he says, ‘but I didn’t think there was a market for it.’

After completing a two-year diploma in model-making at Sunderland Polytechnic and a foundation course at Portsmouth College of Art, he started freelancing. Encouraged by his wife Bryony to exhibit at a local gallery, he saw his paintings ‘fly off the wall. I never looked back — and here I am, after all these years, still doing it. Painting is something I did as a child. It’s not something I made a conscious decision to do as a career — it found me. It has been a rocky road: there have been lean times when I asked myself ‘what the hell am I doing?’. You have to do a balancing act — trying to develop your ability and follow your inspiration, and at the same time [produce the sort of paintings that] make a living.’

Tally Ho — the 1927 Fastnet race: one of Martyn Mackrill’s many yacht portraits, this painting ‘literally fell off my brush. It’s not often that you are satisfied with your own work.’

That living comes principally but not exclusively from the paintings he offers for sale at Messums, the London gallery, where a regular client snapped up the framed King Edward portrait almost as soon as it was hung there. Martyn hastens to add that few of his paintings achieve anything like the price this one commanded: between £2,000 and £3,000 is more common. ‘It’s a precarious living — I never know when the next sale is going to be.’

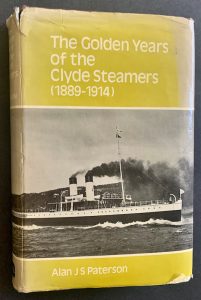

Many of his paintings are of yachts, for which there is a ready market on the south coast of England. He describes the King Edward painting as ‘a milestone for me. It’s something I wanted to do but never dared to do. Maybe I lived on the Clyde in a previous life, but I have an obsession with Clyde steamers that I can’t explain. The first book I bought was Alan Paterson’s The Golden Years of the Clyde Steamers. It became a sort of Bible — every time I read it, I got more interested. I loved that picture of King Edward on the front cover [of the second edition] — the way the smoke was blowing down. I loved the clean line of deck. It captured a moment and triggered something.’

The style of Martyn’s King Edward painting was also influenced by the oeuvre of British artist Norman Wilkinson (1878-1971), particularly his studies of sky and sea — ‘the cloud formations, and how a ship sits and behaves within that. I wanted to capture the vastness of the open Firth and the sweep of the sky.’

He refers to King Edward as ‘a neglected ship in history. It’s time to celebrate her, this wonderful little vessel that sparked a revolution in marine technology in much the same way that electric cars seem to be doing [for automotive power] in our own age.’

Martyn was much preoccupied by the need to get details right — for example, whether to include canvas dodgers on the bridge — in full awareness that specialists in maritime history might pounce and say he had got something wrong.

Inspiration: the dust cover of the 2nd edition of Alan Paterson’s book The Golden Years of the Clyde Steamers. First published in 1969, the book became a Bible for ship lovers, and it was this photo of King Edward that triggered Martyn’s imagination

The bow wave was another tricky question: ‘I have always made a point of studying how ships move and cut through the water. The old Clyde steamers were so narrow, the water tends to slice off and tumble away. Those little things are important. I wanted to include the lighthouse at Toward, but trying to get the lie of the land [on either side] was one of the most difficult aspects. The problem was I couldn’t be certain how close to the land she was.’

Of the technical process, Martyn says the painting took six weeks ‘flat out’ to finish, working five days a week. ‘I loved every minute. I wanted to capture the wind and the movement. It’s very easy to put a lot of ‘white cap’ on the sea, but you can be too clever, and it ends up detracting from the ship. Sometimes the less you put in, the more effective it can be.’

One of the elements of his King Edward painting that pleases him most is that ‘it stands on its own whether you have an interest in Clyde steamers or not.’

Emboldened and encouraged by the success of his first ‘proper’ steamer painting, he promises that there will be more to come. We at CRSC can feel proud that someone of Martyn’s skill and love of the Clyde has used his talents to profile a subject so close to our hearts.

Click here for Martyn Mackrill’s website.

Join CRSC here for £10 and receive all the benefits, including our annual Review of west coast ship movements and 56-page colour magazine, plus specially compiled DVDs, reduced price photo offers and exclusive access to photo-rich ‘members only’ posts on this website.

Published on 24 July 2021