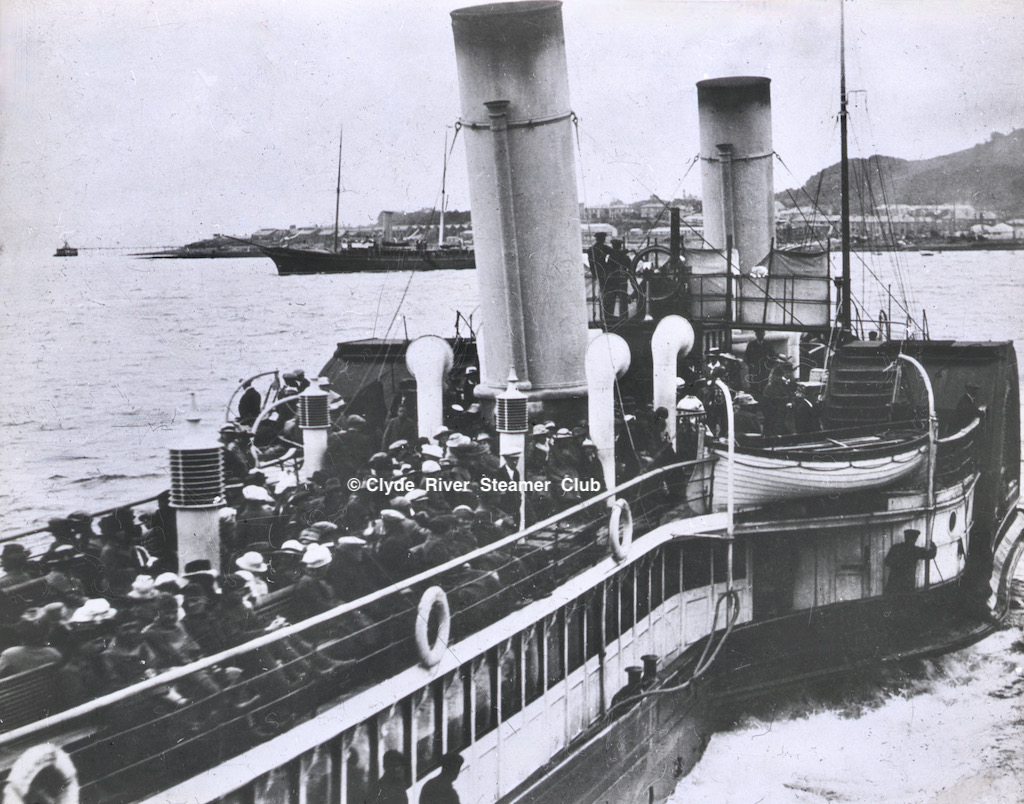

Pictured leaving Gourock, Ivanhoe (1880-1920) was Captain James Williamson’s brainchild: with no liquor on board, she attracted a respectable clientele

The writings of James Williamson and Andrew McQueen were published a century ago and more, but are far from out-of-date: they offer 21st century steamer enthusiasts valuable first-hand accounts of ‘the golden years’. In this first of a series of articles devoted to the two legendary authors, Graeme Hogg compares their accounts of the earliest steamers known to them.

The literature documenting the history of the Clyde steamers is extensive and probably exceeds that for any comparable area of coastal shipping. The Clyde River Steamer Club has played a major role in this, having now published Clyde Steamers for the past 56 years and even more editions of the annual Review. These are published primarily for the benefit of Club members and represent one of the major benefits of membership. For a general readership it also published, in 1971, the masterly The Caledonian Steam Packet Co Ltd by Iain MacArthur, the definitive history of that company. Other well-known works include the various editions of Clyde River and Other Steamers by Duckworth and Langmuir, and Alan J. S. Paterson’s various works. Most recently, Andrew Clark has contributed Pleasures of the Firth: Two Hundred Years of the Clyde Steamers. There are many more.

The first book to deal with the subject in any depth was published in 1904 — Captain James Williamson’s Clyde Passenger Steamers from 1812 to 1901. It is now much sought after either in the original edition or the facsimile reprint produced in 1987. Captain Williamson was one of the most notable members of perhaps the most important family in the history of Clyde steamers. His father, Alexander, founded the family shipping company, which focussed primarily on services to Rothesay and the Kyles of Bute. James was his eldest son and served an engineering apprenticeship with William King and Co, Glasgow, where he helped to construct the engines for Sultana, built in 1868 for his father. He joined the family business, serving as engineer and mate and reputedly taking command of Sultan at the tender age of 20.

Racing was widespread in this era and he was an enthusiastic participant, winding up in front of the River Baillie for his more reckless exploits on numerous occasions. He helped preserve the company’s reputation for good, punctual service. In the off-season, he was based in Glasgow, working at Morton and Williamson, consulting engineers and marine surveyors, which he set up with Robert Morton, a naval architect. Thus, he gained a broad base of experience in all aspects of developing and operating ships and steamer services.

He foresaw that the development of railway connections to the coast would lead to the erosion of ‘all the way’ sailings from Glasgow. He was also unhappy with the drunkenness associated with the ‘doon the watter’ trade. This led him to form a syndicate called the Frith of Clyde Steam Packet Company in 1879 to run a cruise steamer on teetotal lines. Ivanhoe appeared in 1880 and inaugurated the Arran via the Kyles cruise from Helensburgh, Greenock and Wemyss Bay, strictly on temperance lines. There was widespread scepticism that the venture would succeed but, thanks to the quality of the ship and the smart turnout of the crew, Ivanhoe attracted a respectable clientele and became a great commercial success. Sales in Glasgow of the ‘Ivanhoe flask’ also boomed for those who could not cope with a whole day’s abstinence.

Andrew McQueen (1868-1933) became Honorary President of the Clyde River Steamer Club in 1932, the year it was founded

James’s younger brothers, Alexander and John, followed him into the family business, while James concentrated on his new venture, for which he was general manager as well as ship’s captain. His next move came in 1888. The Caledonian Railway was extending its line from Greenock to a new station and pier complex at Gourock. Having met with indifference from private owners who were asked to run connecting steamer services, the Railway decided to develop its own fleet. The first step was to find a Marine Superintendent and James Williamson, as one of the few to come forward, was duly appointed. His innovative and high-quality development of the Caledonian Steam Packet Company revolutionised steamer services on the Firth and has been well documented.

The preface to his book states that ‘a desire has been widely expressed for some permanent record of the rise and progress of the passenger steamer on the Clyde.’ He undertook to provide it on the strength of his active participation in steamer services since 1868. This put him in a position to give something of an insider’s account of steamer history.

The next notable work on the steamers of the Clyde, every bit as sought after today, was not to appear until 1923 and was written from quite a different perspective. Clyde River-Steamers of the Last Fifty Years was written by Andrew McQueen (1868-1933). He was a steamer enthusiast who had known and sailed on the steamers since childhood. He was a regular speaker on the subject in the West of Scotland and was encouraged to amplify the content of his talks into book form.

In the preface he pointed out ‘the present volume, dealing as it does only with the period lying within my own memory, and compiled mainly from personal recollection, is in no sense intended as a rival to Captain Williamson’s delightful history of The Clyde Passenger Steamer, published nearly twenty years ago.’ Nevertheless, McQueen’s book found a ready audience and he attained some eminence in the ranks of steamer enthusiasts. He was a founder member of the Clyde River Steamer Club in 1932, becoming its first Honorary President, partly on the strength of this book and its sequel, Echoes of Old Clyde Paddle Wheels.

The two books were written from different standpoints and cover different periods. Andrew McQueen’s account starts in 1872, while James Williamson’s ends in 1901. This means there is an overlap of some 30 years, spanning a period of significant development in ships and services. Both books describe ships in chronological order and also deal with more general aspects, such as ship layout, machinery and some of the notable personalities. But in all the Clyde steamer literature published between then and now, there has been no comparative study of the way the two books assess certain ships and describe the wider aspects of steamer activity on the Firth in that golden era.

The two books were written from different standpoints and cover different periods. Andrew McQueen’s account starts in 1872, while James Williamson’s ends in 1901. This means there is an overlap of some 30 years, spanning a period of significant development in ships and services. Both books describe ships in chronological order and also deal with more general aspects, such as ship layout, machinery and some of the notable personalities. But in all the Clyde steamer literature published between then and now, there has been no comparative study of the way the two books assess certain ships and describe the wider aspects of steamer activity on the Firth in that golden era.

This will be done over a series of articles, picking out steamers with some connection to one another. For example, the steamers which transformed travel for the tourist in 1877-1880 (the first Lord of the Isles, Columba, Ivanhoe) and the two elite Arran steamers of the 1890s (Duchess of Hamilton and Glen Sannox) make interesting subjects for comparison.

Given his insider role, Captain Williamson (JW) tended to be quite measured when delivering his opinions on the merits or otherwise of the ships he describes. In contrast, Andrew McQueen (AM) was relating personal reminiscences as an enthusiast and was much more open in voicing his opinions.

AM’s book begins by describing the ships in service in 1872, the date he sets for his earliest memories — although, at age four, one wonders how detailed these might have been. The first vessel described is Inveraray Castle of 1839. This steamer was notable for her longevity and the role she played in serving the Kyles of Bute and Loch Fyne throughout her long career. She was built for the Castle Company by Tod and McGregor as Inverary Castle and undertook the Glasgow to Inveraray cargo-and-passenger service for all but one of her 50 years in active service, sailing to Inveraray over the course of one day and returning the next. Her progress was leisurely, making numerous stops en route to set down and uplift cargo and passengers. She subsequently was absorbed into the MacBrayne fleet and the second ‘a’ was incorporated into her name.

AM said that ‘with her red funnel abaft the paddles, her two masts and fiddle bow, she was a graceful old craft….There was an old-world lack of hurry about [the crew’s] methods and a two hour stay at Rothesay was no uncommon occurrence’. The only year she did not sail to Inveraray was in the late 1850s when the Crinan Canal was closed for repairs and she was deployed to sail round the Mull of Kintyre to supplement the regular services. Having been laid up for some time, she was finally scrapped in 1892. She was not one of the more famous ships to serve on the Clyde, but it might have been expected that JW would do more than record the year of her building, although he does include the helpful snippet ‘The Tarbert Castle, built by Wood and Mills in 1836, was wrecked on Ardmarnock beach. Her machinery, however, was afterwards fitted on board the Inveraray Castle, where it did duty until a few years ago’. The machinery in question was an early example of the steeple engine, which was popular through the middle years of the 19th century.

AM said that ‘with her red funnel abaft the paddles, her two masts and fiddle bow, she was a graceful old craft….There was an old-world lack of hurry about [the crew’s] methods and a two hour stay at Rothesay was no uncommon occurrence’. The only year she did not sail to Inveraray was in the late 1850s when the Crinan Canal was closed for repairs and she was deployed to sail round the Mull of Kintyre to supplement the regular services. Having been laid up for some time, she was finally scrapped in 1892. She was not one of the more famous ships to serve on the Clyde, but it might have been expected that JW would do more than record the year of her building, although he does include the helpful snippet ‘The Tarbert Castle, built by Wood and Mills in 1836, was wrecked on Ardmarnock beach. Her machinery, however, was afterwards fitted on board the Inveraray Castle, where it did duty until a few years ago’. The machinery in question was an early example of the steeple engine, which was popular through the middle years of the 19th century.

The most famous steamer of those sailing in 1872 was undoubtedly MacBrayne’s Iona of 1864, which was to grace the waters of the Clyde and Western Isles with distinction until 1935. She was the last of three ships of that name built in fairly quick succession. The previous two had both been sold to the American Confederacy for blockade running to the Southern states, but neither was to make it across the Atlantic.

The first, a flush decked steamer, had been built in 1855 and was sold in 1862. She was run down and sunk close to Gourock as she set out on her delivery voyage and her wreck remains a popular diving site to this day. Her successor, built in 1863, was a more luxurious saloon steamer. Sold at the end of her first season and stripped of deck saloons, she set off for her new life but got no further than the Bristol Channel, being wrecked on Lundy Island early in 1864.

Her successor, also built by J & G Thomson, Govan, was slightly larger and inherited the deck saloons and many internal fittings. The saloons were of the original narrow style with alleyways round the outside. JW described her as ‘the only remaining example of the saloon excursion steamer of forty years ago’. He records that nine years after she entered service she was fitted with Chadburn telegraphs to replace the then commonplace ‘knocker’ for communication between bridge and engine room. She was also fitted with steam steering gear, a first for a Clyde steamer. ‘Both these installations were considered great additions to the efficiency of the vessel.’

AM did not provide any more detail of the ship herself, but referring to her longevity, commented ‘people are sceptical when told her age….There seems to be an impression in some quarters that a new Iona is built every ten years or so’. He does go into some detail on her employment, which was on the Glasgow-Ardrishaig service until the advent of Columba in 1878. Thereafter she supplemented Columba’s sailings in various ways between spells on sailings from Oban. She sailed only in summer and ‘she bears her years lightly and is still a handsome boat, and, while not exactly a greyhound now, can still attain a very respectable speed’. Since she continued in service for a further 12 years after AM’s book was written, achieving a total of over 70 years, neither author really accords her the full eminence she was to attain after her withdrawal.

Inveraray Castle at Rothesay in the 1880s. Williamson dispassionately noted that her machinery had been inherited from Tarbert Castle, while McQueen observed ‘an old-world lack of hurry about [the crew’s] methods and a two hour stay at Rothesay was no uncommon occurrence’

Ivanhoe at Gourock c1905, now a Caley steamer — and still under the management of ‘Captain James’. Duchess of Montrose lies beyond