The world as Williamson and McQueen knew it: three privately owned paddlers race past Greenock c1887, illustrating various late 19th century advances in onboard accommodation. Viceroy of 1875 (foreground, in Captain Alexander Williamson Snr’s colours of black funnel with white band) is a typical raised quarterdeck steamer: a few years after this photograph was taken, she would be taken over by the G&SWR and given fore and aft deckhouses. In the middle is the Lochlong & Lochgoil Co’s Chancellor of 1880, with deckhouses surrounded by alleyways. Furthest from the camera is Gillies & Campbell’s Victoria of 1886 (two white funnels with black top), which had full-width deckhouses and electric lighting

For anyone interested in Clyde steamer history, two books dating from a century ago and more — still available on the secondhand market — provide valuable information about the design, appearance and workings of late 19th century fleets. In each case — Captain James Williamson’s Clyde Passenger Steamers from 1812 to 1901 (1904) and Andrew McQueen’s Clyde River-Steamers of the Last Fifty Years (1923) — the author used personal experience of the ships to illuminate his descriptions.

Graeme Hogg, in his ongoing review of excerpts from the two books, now turns his attention from the ships themselves to onboard conditions.

We are fortunate that, in addition to discussing the ships, James Williamson and Andrew McQueen gave us a flavour of their layout, including those of flush deck or raised quarter deck design, and what travelling on them was like.

Writing after the First World War, and drawing on his experience of the various changes in Clyde steamer design over the previous 50 years, McQueen described how almost all steamers on the Firth in the 1860s were paddle-driven, mostly “flush-decked with a hurricane-deck over the engine-house, a type of vessel that has long since disappeared. All had small side-houses built on the forward sponsons; one of these, usually the one on the port side, being fitted up as a galley; whose narrow funnel stuck up above the hurricane-deck just forward of the paddle-box, while the house on the starboard side contained lavatory arrangements of the primitive style then deemed adequate. The bulwarks of the after-deck were often surmounted by a canvas screen, serving to protect the passengers from spray, and at the same time to shut out the view of everything but the sky from anyone under middle height. The cabins, under the main-deck, entered usually from the after end, were stuffy little vaults with scant headroom, to which the light found its way partly through a few round ports near the water-line, and partly through a skylight on the main-deck.”

Balmoral, built in 1842 as Lady Brisbane and pictured here in the 1880s, was a late-surviving example of the flush-deck design

The advent in the late 1860s/early 1870s of raised-quarterdeck boats, numbering about a dozen, marked a significant advance: they were far more comfortable than the flush-deckers. These steamers had the deck abaft the engine-house raised to the level of the main-rail. This arrangement secured a considerable increase of headroom and vastly improved ventilation. Most of the earlier boats of this type had their cabins lit by a row of square windows set close together, admitting plenty of light, but the system probably had its drawbacks, as all the raised-quarterdeck boats after 1868 had ordinary circular ports. The entrance to the cabin in all the boats of this class was at the break of the quarterdeck, under the stairway leading down from the hurricane-deck.

McQueen noted that an open rail surrounding the raised deck offered no obstruction to the view, enabling even the tiniest tots to enjoy the fascination of watching the ‘soapy sapples’ churned up by the paddle-wheel. From his vantage point of the early 1920s, he pointed out that “the last survivor of this class, the Benmore, is not likely to see further service.”

Before Columba in 1878, the only steamers with deck saloons were Iona, Chevalier (an occasional visitor), the 1866 Dandie Dinmont, the 1880 Chancellor, Kingstown and Bonnie Doon. None of these saloons (apart from Columba’s) extended the full width of the vessel. McQueen said the 1880s saw an increased demand for comfort, leading to the addition of short deck-saloons on a number of well-established flush-decked boats — Sultan, Sultana, Marquis of Bute, Vivid, Adela and Argyle being among those fitted out in this way.

Captain Alex Williamson Jnr (top row, centre) with the crew of his father’s Glasgow-Rothesay flier Sultana c1885. Alex Williamson Jnr was James Williamson’s younger brother: both went on to transform standards of accommodation and design in Firth of Clyde steamers in the 1890s. Click on image to enlarge

By modern standards, of course, the steamers in those days were quite primitive. McQueen recalled how, up to the mid 1870s, “few of the boats had navigating bridges, and the engine-room telegraph was a thing unknown; the skipper stood on the paddle-box and transmitted his orders to the engineer by means of a brass-headed knocker in the rail; three strokes for ‘Go ahead’, two for ‘Back her’, and one for ‘Stop her’. There was no steam steering-gear: the hand-wheel, about as tall as an average man, stood on the hurricane-deck between the paddle-boxes, and just behind it was a low table, on which the steersman stood. So far as I can remember there were no steam-whistles then, but a warning bell was rung when small boats threatened to get in the way.”

The engines of the period were evenly divided between the steeple, oscillating and diagonal types, although the last-mentioned was coming gradually into favour and superseding the other two. “As a small boy,” McQueen remembered, “I had a strong preference for the steeple-engined boats. The engine-rooms of those days were completely boxed in, the windows being far above my low head, and if the engine were of diagonal or oscillating design, I could only hope to get an all too brief glimpse of it when raised in the parental arms. In a steeple-engined boat, the crosshead, bobbing up and down like a jack-in-the-box, was in full view and could be watched at leisure, independent of parental assistance.”

With the possible exception of David Hutcheson’s steamers, not much was attempted in the way of uniform: the skipper wore a brass-bound cap, says McQueen: otherwise there was often nothing nautical about his attire. “The deck hands usually had blue woollen jerseys with the steamer’s name worked in red in front. In the engine-room, dongarees and an oil-can were the insignia of the profession. Some of the old-time skippers, such as Captain Barr of the Lochgoil boats, and Captain McLean of Marquis of Bute, eschewed even the nautical cap and wore square-topped felt hats; McLean, indeed, had a white silk ‘tile’ for special occasions. The captains of those days undertook the duties of purser besides attending to the navigation of the vessel. McLean, while performing either of these functions, never forgot that he was owner of the vessel as well, and the care he exercised to avoid any scraping of paint or gilt-work in taking a pier was only equalled by his diligence in inquiring the exact age of any child who seemed to be near the half-fare limit.”

Of the ships built after 1872, several were still of the flush deck or raised quarter deck design, but as that decade progressed, the saloon steamer became the norm. However, the older types remained in service and, as noted above, Benmore survived to the end of the First World War. Engine room telegraphs and steam steering appeared in the 1870s, Iona being the first to become so equipped in 1873.

Elaine of 1867, pictured off the Greenock Esplanade, was a typical raised quarterdeck steamer: you can see the square windows lighting up the cabin aft of the paddle box

Reference is made above to the different types of machinery used to propel the steamers of the time. James Williamson, who included engineering skills among his accomplishments, was always an advocate of embracing the latest advances in marine engineering. In his classic 1904 volume he looked back on the planning for his Ivanhoe in 1879 and complained about the conservatism of shipbuilders of the time.

“It will doubtless seem incredible that in 1879, when the writer was negotiating for the building of the Ivanhoe, the compound engine was condemned for river traffic by all the Clyde engineers with one exception,” he wrote. “The exception was the firm of Rankin & Blackmore of Greenock, and often afterwards, I regretted that I did not accept their recommendation.”

He went on to lament: “Even the Swiss had compound paddle steamers on their lakes twenty years before us”.

This may have been down to the fact that they had no coal of their own and had to import it, increasing their emphasis on fuel economy. Williamson did have a bee in his bonnet on this subject. When discussing Grenadier of 1885, which was fitted with the first, and possibly last, compound surface condensing oscillating engine, he noted: “The circumstance [the choice of machinery] reveals a very strange state of affairs. It might be said to be the reverse of complimentary to Clyde steamboat owners. From the early years of the century, these owners enjoyed the reputation of possessing the finest and most up to date fleet in the world, yet they continued down to 1885 to employ engines which were by no means the latest or most economical. The reasons were probably to be found in the cheapness of coal and the imminence of railway extensions and competition.”

The enclosed engine rooms of the 1870s gave way to the uninterrupted view of the 1890s — as illustrated here by the 1892 Glen Sannox. Click on image to enlarge

When Captain James took up the reins of the Caledonian Steam Packet Company from 1889, he had the authority and the resources to implement his engineering philosophy, to the benefit of all.

The enclosed engine rooms of the 1870s also gradually disappeared. By the 1890s an uninterrupted view of the rotating cranks, so familiar from the present Waverley, had become the norm.

Surprisingly, neither author devotes much coverage to catering. As the relocation of the dining saloon to the main deck was not to happen until King George V of 1926, all late 19th century steamers had their dining saloon — to the extent that they had one — on the lower deck.

The sole exception was the North British Railway’s Lady Rowena. Her dining saloon was situated in the forward saloon which, unusually, was the full width of the hull.

There is occasional mention of the quality of the catering on the tourist steamers.

Williamson points out that, in the case of the first Lord of the Isles, “much of its success was also due to the exertions of the late Mr David Sutherland, who had charge of the cuisine”.

It is an indication of the importance attached to catering on the tourist steamers that Duncan Newlands, chief steward of the 1877 Lord of the Isles, featured in the well-known Glasgow journal The Bailie at the height of the 1888 season

As might be expected, he gives quite a bit of coverage to Ivanhoe, referring to the floral decorations in the dining saloon, an innovation, and the presence of grape vines trained round the walls of the same compartment: these produced bunches of grapes, which would be cut on special occasions.

McQueen described Columba as “representing all that is best in accommodation and catering.” Generally, catering on these steamers was more formal than in later years, with extensive luncheons and high teas the order of the day. Tearooms emerged later in the period.

In his concluding chapter McQueen provides a neat overview of the changes in on-board accommodation.

He comments: “The constantly growing demand for greater luxury in travel has brought about a continuous improvement in the comfort of the boats, until at length the old flush-deckers and raised-quarterdeck boats have disappeared, and we have a fleet composed entirely of steamers equipped with luxuriously furnished deck saloons, well lighted and ventilated.”

In the light of the intervening 100 years since McQueen’s book was published, his observation about the constantly growing demand for greater luxury in travel sounds remarkably contemporary, even if his closing remarks have a distinctly ‘period’ feel: “Dainty tea-rooms and well-furnished sweet and book stalls, formerly undreamt of, are now regarded as essential parts of a steamer’s outfit.”

Read more steamer stories on the CRSC website by clicking on News & Reports.

Vivid, a flush-deck steamer when built for Captain Bob Campbell’s Glasgow-Kilmun trade in 1864, is pictured with the short aft deck saloon that was added in the 1880s, after she had joined Captain William Buchanan’s fleet. She was broken up in 1902

The first Jeanie Deans was built in 1884 as a raised quarterdeck steamer, with circular portholes in place of the square saloon windows fitted to her raised quarterdeck predecessors. In this view of her leaving the North British railhead at Craigendoran, passengers can be seen at the open rail of the raised deck, enjoying the sight of the ‘soapy sapples’ churned up by the paddle-wheel

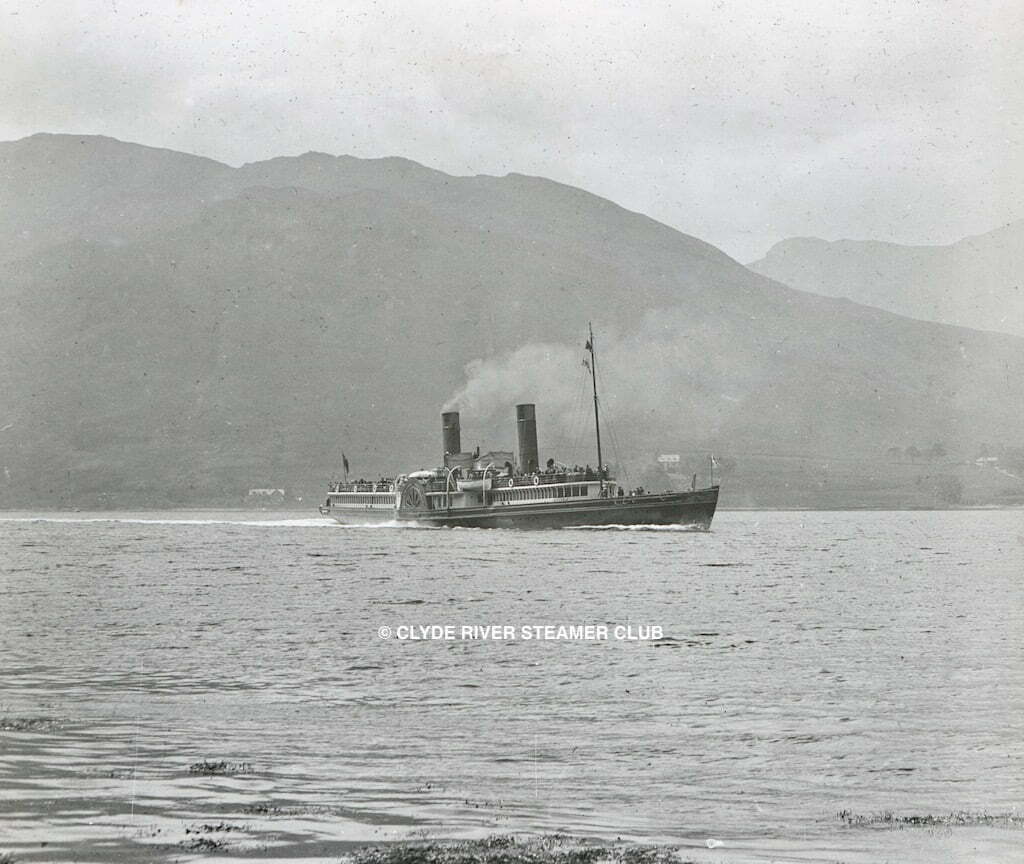

In 1896, two years after being fitted with deck saloons fore and aft, Jeanie Deans was sold to a Londonderry owner, only to return to the Clyde in 1898 as Duchess of York, under the auspices of Andrew Dawson Reid. In 1904 she was purchased by Buchanan Steamers and renamed Isle of Cumbrae, and it is in this guise that she is seen approaching Tighnabruaich. She was broken up after the First World War

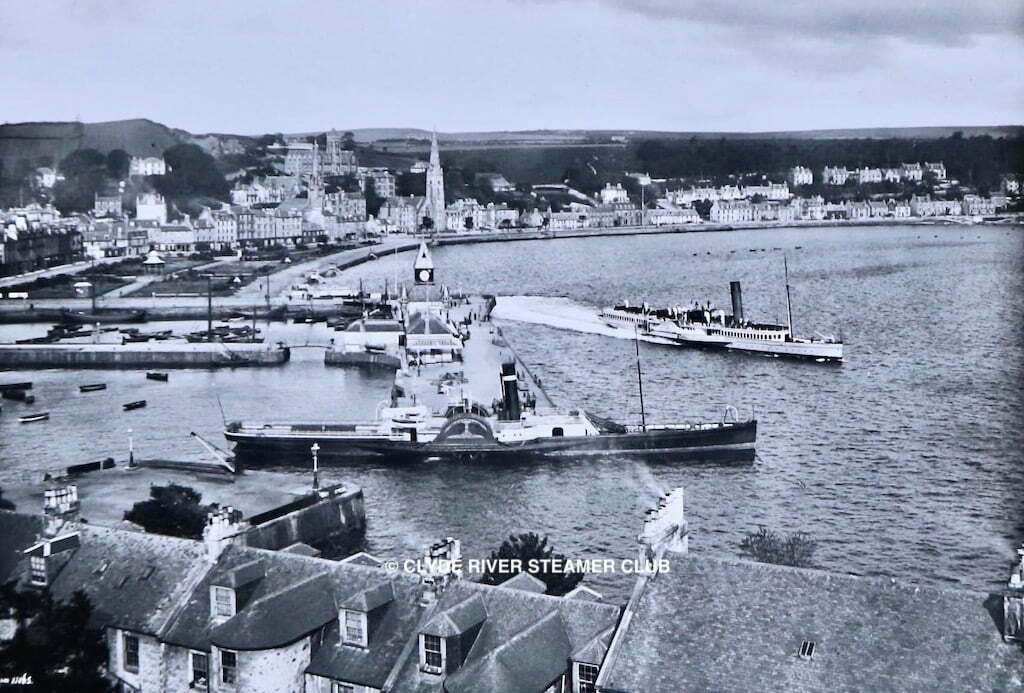

Benmore (foreground) and Mercury at Rothesay in 1892, the G&SWR steamer’s first season and Benmore’s last under the ownership of Captain William Buchanan (she was sold later that year to Captain John Williamson, youngest of the three Williamson brothers). Benmore was the only raised quarterdeck steamer to survive to the end of the First World War

The brand-new Lady Rowena in July 1895 off the Cloch, during the Royal Clyde Yacht Club regatta. Unusually, her dining saloon was situated in the forward saloon which was the full width of the hull

Iona of 1864, emerging from the East Kyle en route from Ardrishaig to Glasgow in the 1920s. The third MacBrayne steamer to bear the name Iona, she inherited from her short-lived 1863 predecessor the deck saloons which marked her out as one of the most sophisticated steamers of the mid Victorian period, bringing considerable allure to the ‘Royal Route’. She struck a further advance in 1873 when she became one of the first vessels to be fitted with steam steering gear and Chadburn engine telegraphs

SEE ALSO:

Published on 11 March 2022