Head to head: for 15 years, from the debut of Glen Sannox (right) in 1892 until the 1909 agreement by the CSP and G&SW to ‘pool’ their Clyde services, Arran had the fastest and most competitive service it has ever enjoyed. The G&SW’s ‘Sannox’ is pictured with her CSP arch-rival Duchess of Hamilton (left) at Whiting Bay c1896, three years before a pier was built there

In the latest in his series on the pioneering books of Captain James Williamson (Clyde Passenger Steamers from 1812 to 1901) and Andrew McQueen (Clyde River-Steamers of the Last Fifty Years), Graeme Hogg compares the two authors’ accounts of the railway steamers which dramatically raised standards on the Arran service in the 1890s and 1900s.

Until 1890 the service to Arran from Ardrossan was the preserve of the Glasgow & South Western Railway (G&SW). Its trains ran from St Enoch Station in Glasgow to Ardrossan Harbour and, while it did not operate steamers in its own right, it provided timetabled connections with Scotia, owned by Captain William Buchanan. She had been built in 1880 by McIntyre of Paisley and was described by Captain James Williamson as “no beauty”. She was 211 feet long, had two funnels fore and aft of the paddles, a deck saloon aft and, by this time, a raised fo’c’s’le as protection from the exposed conditions on the Arran run. She was something of an anachronism, being fitted with the last steeple engine to be installed in a Clyde steamer. She provided a steady but unspectacular service to the island.

Captain James Williamson (right), CSP marine superintendent and architect of the rapid advances in Clyde steamer design in the 1880s and 1890s, stands on the deck of Duchess of Fife on 20 May 1903, the day of her preliminary trials. Click on image to enlarge

All this was to change. First, by 1889 the Caledonian Railway had completed its rail link to Gourock, giving it the most advantageous terminus for upper firth destinations like Dunoon and the Holy Loch. Having found private operators reluctant to provide services, the Railway decided to provide its own, circumventing parliamentary resistance by setting up a subsidiary company, the Caledonian Steam Packet Company (CSP), which bought existing steamers and ordered new ones.

These moves were masterminded by Captain James Williamson, eldest son of one of the leading mid century private steamer operators on the Clyde, who had been appointed the CSP’s new Marine Superintendent. The Gourock-based ships also provided stiff competition to those of the Wemyss Bay Steamboat Company, operated by Campbell & Gillies, to Rothesay.

Writing 14 years later in his still sought-after book, Williamson drew on his own personal experience of events to describe what happened. “The Wemyss Bay Steamboat Company, thinking to interrupt the traffic and coerce the Railway Company, gave one week’s notice, instead of six months’ and withdrew their service of steamers. But no interruption occurred. The Caledonian Company placed its new steamers on the station and the traffic went on as before. The only result was that the old Wemyss Bay Company’s vessels were first laid up and then disposed of”.

The CSP, perhaps anticipating problems along these lines, had just taken delivery of two ships, Marchioness of Breadalbane and Marchioness of Bute, and they took over services to Bute and Cumbrae.

Having secured the traffic via Gourock and Wemyss Bay, Arran became the focus of attention. The new Lanarkshire and Ayrshire Railway completed a connection to Ardrossan to permit, on 1 June 1890, the introduction of a notable vessel for the CSP on the Arran run.

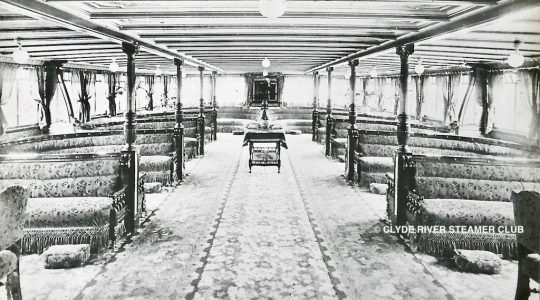

Captain Williamson describes her thus: “This steamer, the Duchess of Hamilton, built and engined by Denny Brothers, was and still is, beyond doubt the finest and most successful craft in Clyde passenger traffic. Her principal dimensions are 250x30x10 ft., and her general arrangements are of the most commodious character. The promenade deck extends the entire length and width of the vessel, being the first of this kind to be built. On the main deck are the general saloon aft, and the second-class saloon and smoking room forward. Under the main deck are the respective first and second class dining saloons, and sleeping accommodation for the crew. As a testimony to the perfection of the arrangements on board, it may be stated that the Committee of the Clyde Yachting Clubs will have no other steamer to act as Club boat during the Clyde yachting fortnight.”

Scotia, still in Buchanan colours, approaches Ardrossan Harbour in the summer of 1890, with the new CSP paddler Duchess of Hamilton hot on her heels

Williamson was, inevitably, going to be partial to his flagship but Andrew McQueen, writing 20 years later (1923), was almost as impressed. “This proved to be one of the most successful boats ever seen on the Firth. Her immense saloon, thirty feet in width, was sumptuously furnished; her promenade deck extended the full length and width of the vessel and the symmetry and balance of her whole design rendered her a joy to look upon. Her popularity was at once assured, and her superiority over the old Scotia secured for the new route the major portion of the traffic.”

In spite of these eulogies, Duchess of Hamilton lacked sheer in her hull design and was not as graceful or attractive as some of her successors, notably Duchess of Rothesay (1896) and Duchess of Fife (1903).

The new ship continued Williamson’s philosophy of utilising the latest technology. She was equipped with a two crank compound diagonal engine powered by three navy boilers. She also pioneered the Parsons steam turbine to generate electricity on board.

Her full-length promenade deck was open at the front to permit the handling of ropes and, oddly, her forward saloon had alleyways round it, limiting the covered accommodation, but maybe preventing drafts by avoiding a saloon entrance near the bow.

The G&SW realised it faced a serious challenge from the CSP across all its routes via Princes Pier, Fairlie and Ardrossan. Its solution was to develop its own fleet, run as part of the railway company and presided over by Alexander Williamson, JW’s younger brother, who already had a relationship with the Railway, having provided the main Rothesay connections for many years. His family fleet was acquired, as was Scotia from Captain Buchanan. A programme of new builds was also begun, the philosophy being to outdo the corresponding CSP ships in each case.

Scotia had been completely outclassed and had to be replaced as soon as possible to wrestle back at least some of the traffic lost to Duchess of Hamilton.

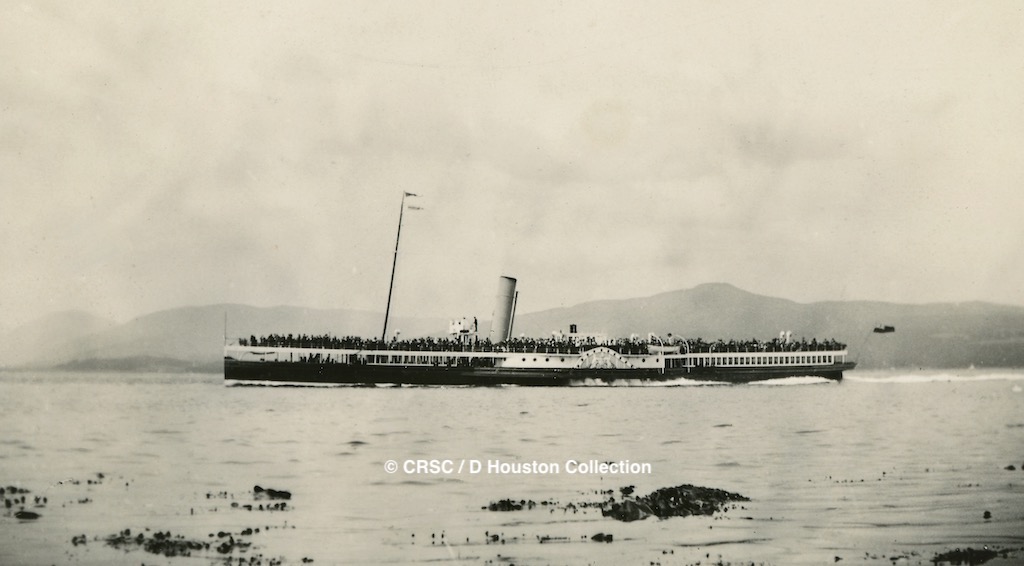

J & G Thomson of Clydebank were awarded the contract to build the new G&SW Arran steamer, which was enthusiastically described by Andrew McQueen in the following terms: “The Glen Sannox … was some ten feet longer than the Duchess of Hamilton, and furnished in equally lavish manner. Her engines were the same type as those of the Duchess, but more powerful and she was a faster boat. Her side plating, from the bow to the forward end of the saloon, was carried right up to the promenade deck and, with her two smartly-raked funnels, she presented an imposing appearance.”

As might be expected, Williamson slightly damns with faint praise when describing the ship. “She was unquestionably a fine steamer, being somewhat similar to the Duchess of Hamilton in design, finish and equipment, but ten feet longer. Only, in her engine room, about double the power and double the fuel had to be expended in order to get a knot more than her rival on the Ardrossan and Arran route.”

Neither account really conveys the beauty of this ship, resplendent in the G&SW colour scheme of dove grey hull, white upperworks and deep red funnels with black tops.

With two such outstanding steamers on the service, Arran enjoyed its best ever service. The fastest crossings resulted in Glasgow to Brodick times of only 85 minutes. Today’s best time is 117 minutes. However, feuing on Arran was strictly controlled and, while traffic increased through the decade, it could never expand to the extent that two such large, expensive ships could operate profitably. Attempts were made to reduce direct competition, such as routing Duchess of Hamilton via Whiting Bay in the first instance, while Glen Sannox went via Brodick, but neither company was content to risk the other gaining the upper hand, and such initiatives had limited success.

The next change came in 1906, when Duchess of Hamilton was supplanted on the CSP service by Duchess of Argyll. The new turbine was comfortably faster than Glen Sannox and overshadowed her to some extent, although the paddler retained a lot of the affection of Arran travellers.

Competition across the network was unsustainable and, from 1909, a pooled timetable was introduced, resulting in the Arran service being operated by only one company each year. The speed and quality of the Arran service would never be as good again.

After the appearance of Duchess of Argyll, Duchess of Hamilton was redeployed on cruises from Gourock. She was just as popular in this role. Glen Sannox was also to be found sailing further afield in the years it was the CSP’s turn to supply the Arran steamer, but she was more limited in the places she could visit owing to operating constraints placed on directly railway owned steamers. When war was declared in 1914, many Clyde steamers were called up for war service as troopships or minesweepers. Duchess of Hamilton was requisitioned as a minesweeper in 1915. She survived only a few months, being blown up off Harwich in November of that year.

In later years Glen Sannox was a shadow of her former self. She is pictured at Greenock early in 1925, before being sent to the breakers

Glen Sannox was also called up in 1915 for trooping. She sailed south but was quickly returned as unsuitable. The reason was never disclosed, but her very heavy coal consumption may have been the reason. She resumed the Arran run for the duration. In post war years, she continued mainly on the Arran service and passed into the hands of the London Midland & Scottish Railway following the railway groupings of 1923, adopting the alien yellow funnel, albeit with a G&SW red stripe separating it from the black top. However, she was in need of expensive remedial work, especially to her boilers, and the decision was taken to withdraw her from service after the 1924 season. She was broken up in Port Glasgow in 1925.

It is sad that two such notable steamers enjoyed such relatively short careers. For many years it was possible to view one of the ornate paddle box crests from Duchess of Hamilton on the passenger walkway at Wemyss Bay piers, but it disappeared during one of the refurbishments to the structure.

Therefore, apart from a name pennant and the builder’s half-model which The Isle of Arran Heritage Museum has on long-term loan from CRSC, all we have are photographs to remind us of two ships which represented the epitome of the late Victorian Clyde paddle steamer.

As part of an initiative to organise and catalogue artefacts in the CRSC Collection, William Tomlinson (left, Curator) recently uncovered the name pennant of the 1892 Glen Sannox. Despite having been flown from the foremast of the paddler, the flag is in remarkably good condition

After being dislodged from the Arran service in 1906 by the new turbine Duchess of Argyll, Duchess of Hamilton was moved up-firth to give excursions from Gourock. She is pictured off Craigmore c1910

Duchess of Argyll in her original condition, with saloon windows forward on the main deck and an open rope-handling area at the bow. Both features were plated-in in 1910

Crew of Duchess of Argyll in 1906. Captain Alex McKellar sits in the middle, with chief engineer Alex McKenzie third left and mate John McNaughton third right. McNaughton later became the master most closely associated with the much loved CSP turbine

Paid-up CRSC members can view dozens of photographs of the early CSP and G&SW fleets in the following ‘Members Only’ posts:

One Thousand and One Gems from the CRSC Archive: early Caley paddlers

One Thousand and One Gems from the CRSC Archive: Sou’West Steamers