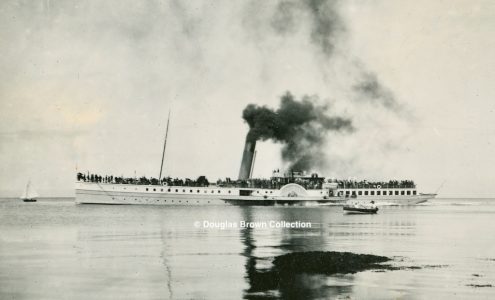

Landing at Corrie: a swarm of rowing boats clusters round Jupiter as she makes the first Arran call on her excursion from Greenock via the Kyles

Continuing his comparative study of the writings of James Williamson and Andrew McQueen, pioneers of Clyde steamer literature, Graeme Hogg examines how railway company rivalry on the ‘Arran via the Kyles’ excursion in the 1890s focused on two crack paddle steamers.

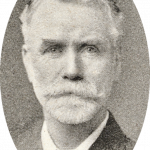

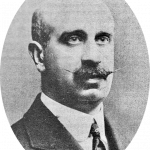

Captain James Williamson (1852-1919). His book Clyde Passenger Steamers from 1812 to 1901 was published in 1904. It was the first comprehensive study of steamer history on the Firth

The ‘Arran via the Kyles’ excursion had been introduced by Ivanhoe when she first appeared in 1880. A combination of the beautiful scenery and the high quality of the ship, including her teetotal principles, led to major success in the ensuing years. Ivanhoe had a brief sojourn on the Manchester Ship Canal in early 1894 but returned to her old haunts thereafter, still managed by James Williamson who, from the late 1880s, also happened to be the marine superintendent of the Caledonian Steam Packet Company (CSP).

From the outset, Ivanhoe had started her cruise from Helensburgh and called at Princes Pier and Wemyss Bay. Craigendoran had been incorporated after that pier opened in 1882, and Gourock replaced Wemyss Bay in due course, resulting in connections with all three railway companies serving the Clyde coast. However, relations with the North British and Glasgow & South Western Railways soured, such that Ivanhoe became closely allied to the CSP’s Gourock route.

After establishing their own steamer fleets in 1889-90, the CSP and Glasgow & South Western Railway (G&SW) initially concentrated on railway connection services to the coast, serving the Holy Loch, Dunoon, Rothesay, Millport and Arran and, in the case of the G&SW, the Kyles of Bute. Competition was white hot, bolstered by the fact that the marine superintendent for the G&SW was Alexander Williamson, younger brother of James. Each company sought to outdo the other, whether in the quality of ships or the convenience and speed of services.

Andrew McQueen (1868-1933) became Honorary President of the Clyde River Steamer Club in 1932, the year it was founded. His knowledge of the late Victorian era shone through his books, Clyde River-Steamers of the Last Fifty Years (1923) and Echoes of Old Clyde Paddle Wheels (1924)

Having reached a degree of equilibrium by the mid 1890s, the G&SW decided in 1894 to deploy Neptune on the ‘Arran via the Kyles’ excursion, in direct competition with Ivanhoe. James Williamson took a dim view of this move, complaining in the first instance to the G&SW before pursuing the matter through the Court of Session, on the grounds that the G&SW was exceeding its operating limits and had spent more than authorised in developing its fleet. This was to no avail: Ivanhoe now faced stiff opposition.

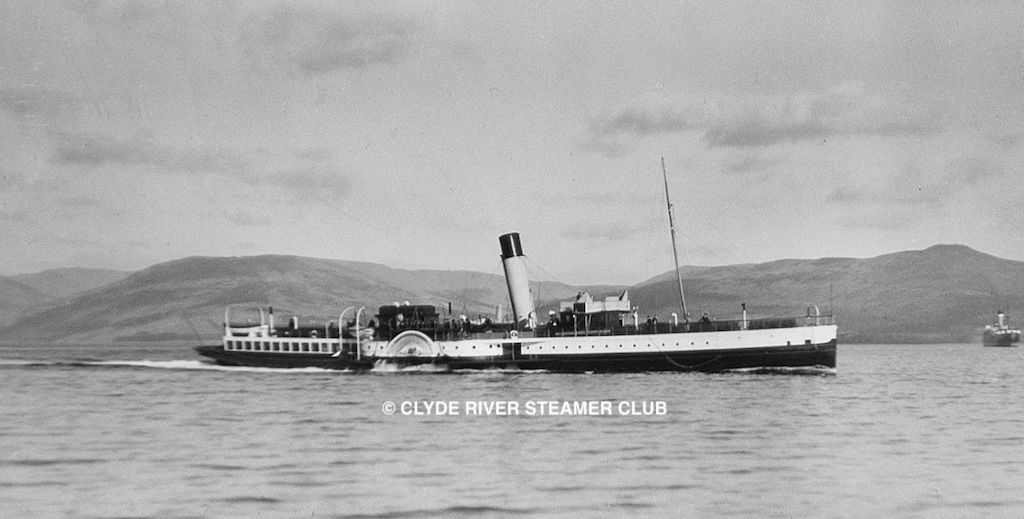

The CSP made a notable addition to its fleet in 1895. James Williamson described Duchess of Rothesay’s arrival thus: “The boat was built by the Clydebank Shipbuilding Company [successor to J & G Thomson, and renamed John Brown and Company in 1899] … An up-to-date vessel in every respect, she proved a valuable acquisition to her owners … For many years, she was “cock of the walk” on the firth, being certainly the smartest looking craft turned out by the Clydebank firm”.

Andrew McQueen gave a more measured description: “The Duchess of Rothesay is a Clydebank boat, compound engine, a smaller boat than the Duchess of Hamilton, but something like her in general design.”

She was in fact some 25 feet shorter than the ‘Hamilton’ and differed from her in having her fore saloon the full width of the hull. With a steeply raked funnel and perceptible sheer, she was also more elegant in appearance and had a considerable turn of speed. The “cock of the walk” designation came from the fact that she carried a weather-vane at the top of her mast in her early years, but it also reflected the esteem with which she was regarded.

When new she was employed on railway connection work from Gourock and was more than a match for the G&SW opposition. However, James Williamson notes: “Upon the appearance of this vessel the Glasgow and South Western and the Caledonian Companies concluded an armistice of five years. The arrangement was not, in all respects, advantageous to the latter company, whose geographical advantages would doubtless have overcome their rivals, but it was wise to put a stop, by friendly means, to a reckless competition, which might have ended in disastrous results”.

A wooden ferryboat attends to Duchess of Rothesay at Corrie c1900 — the event of the day for a small community on the east coast of Arran. Graced with some of the most harmonious lines of any Clyde steamer, the ‘Rothesay’ was a familiar sight on the ‘Arran via the Kyles’ excursion in the late 1890s and early 1900s, competing with the G&SW’s Jupiter until a pooling arrangement in 1909 brought an end to the ruinous duplication of services by steamer-operating railway companies. Duchess of Rothesay survived both world wars and was broken up in 1946. Click on image to enlarge

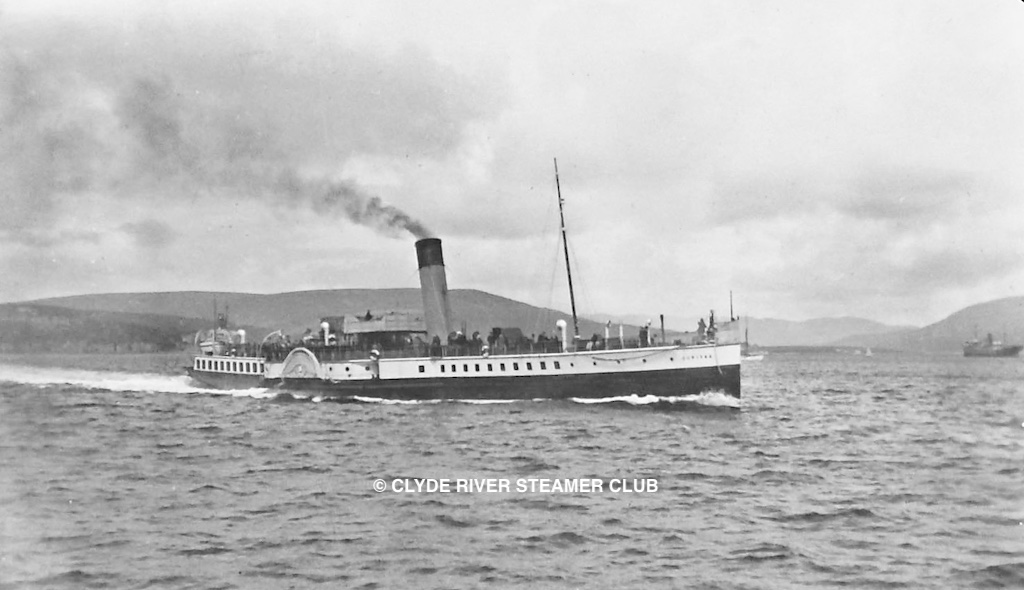

Nevertheless, as was the pattern of the era, the G&SW retaliated by ordering a flier of their own for the 1896 season. Jupiter was also a product of the Clydebank yard. Williamson states: “She was smaller than Glen Sannox, but in most other respects, was of the same design and finish. Clydebank, indeed, has become famous for the building of this class of steamer, the majority of the type produced during the decade having been put upon the water by this firm. In appearance and finish they have been second to none, and all of them may be considered successful boats”. McQueen described her as “comfortable and fast”. She was some five feet longer than Duchess of Rothesay and just as fast, achieving over 18 knots on trial. Her hull design was similar to Glen Sannox, but she carried only one funnel. She was more imposing in appearance than Duchess of Rothesay, but just as attractive.

She entered service replacing Neptune on the ‘Arran via the Kyles’ excursion, offering even more formidable competition to Ivanhoe. James Williamson and the CSP reacted by purchasing Ivanhoe late in 1896 and, from 1897 onwards, utilising her on general excursion and railway connection work. Her place on the ‘Arran via the Kyles’ excursion was taken by Duchess of Rothesay. This meant that the G&SW and CSP were now well matched in a rivalry that was to last a dozen years until the pooling arrangements of 1909, when Duchess of Hamilton, displaced from the CSP Arran service, took over from both ships.

The two ships followed the same route daily except Sundays, Jupiter departing from Princes Pier and Duchess of Rothesay from Gourock, the latter leaving slightly earlier to avoid neck-and-neck racing. The cruise was one of the most popular on offer, giving passengers a wide variety of scenery. Both made calls at Dunoon, Rothesay and Tighnabruaich, before heading down the West Kyle towards Arran. The ferry call at Corrie was the highlight of the day for the east Arran village. Further calls were made at Brodick and Lamlash. A second ferry call was made at King’s Cross, although Duchess of Rothesay stopped calling there in 1901. Finally, Whiting Bay was reached. The return journey retraced the steps along the Arran coast, but after Corrie the route was the more direct one via Garroch Head to the upper firth piers. Any Tighnabruaich passengers would have had to make a late connection from Rothesay. In spite of the popularity of the cruise, Williamson commented that “the combined business of the two has never been equal to that of the Ivanhoe in its early days on the same route”.

From 1909, the two rivals were utilised more on railway connection work, with occasional cruising. Both were to enjoy reasonably lengthy careers. Duchess of Rothesay served her country in both world wars. In the first, she had a glittering career as minesweeper, on one occasion towing a stricken Zeppelin back to Margate and dealing with some 500 mines during the conflict. For the latter part of the war she was renamed Duke of Rothesay. As she awaited refit at Merklands in 1919, a sea cock left open in error resulted in her sinking alongside the quay. She was refloated, no lasting damage having occurred, but it was 1920 before she returned to peacetime service. Between the wars she was chiefly associated with services to Dunoon, Rothesay and the Kyles, but in 1939 she revisited the haunts of her youth with a stint on the Arran via the Kyles’ sailing.

She could still perform at a high level. On a trial in 1935 she achieved 17.5 knots, only slightly less than her original trial speed of 17.77 knots 40 years before. Called up again in 1939, she served as a minesweeper and was involved at Dunkirk. Later in the war she became an accommodation ship at Harwich. She was never to return to home waters. After being beached for a time at Brightlingsea, she was sold for scrapping in the Netherlands in 1946.

Jupiter was also requisitioned for minesweeping duties in the First World War, being renamed Jupiter II, based at Dover. On her return to peacetime duties in 1920, she was given mainly cruising duties, initially between Greenock and Ayr and later, following the railway groupings (which saw her lose her distinctive grey hull and red and black funnel colours), on various cruises including ‘Round the Lochs’. Time was not as kind to her as to her erstwhile rival and, by 1934, she had been relegated to more mundane duties, becoming the Wemyss Bay-Millport steamer. She had lost much of her former verve and was to last only until the end of 1935, when she was sold for scrapping at Barrow.

In their heyday, these striking steamers brought style, colour and glamour to the ‘Arran via the Kyles’ excursion, and helped cement it as one of the most popular of the Clyde cruises until the 1970s.

Duchess of Rothesay (centre), flanked by Galatea (left) and Duchess of Hamilton (right), began her day at the CSP’s Gourock railhead, which provided berths for several steamers at one time

Jupiter (left) was based at Greenock’s Princes Pier, where she is seen with the Campbeltown company’s Davaar

Duchess of Rothesay’s fine lines are seen to advantage in this photograph of Craigmore pier dating from 1922, with the G&SW’s Glen Rosa about to pass on her way to Rothesay

After lying submerged for three months at Merklands in 1919, Duchess of Rothesay was refloated on 28 July by the cofferdam method — a 16-ft high structure bolted to the sides of her hull, from which water was pumped out, steam being supplied by donkey boilers on the quayside. After reconditioning Duchess of Rothesay resumed peacetime service in 1920